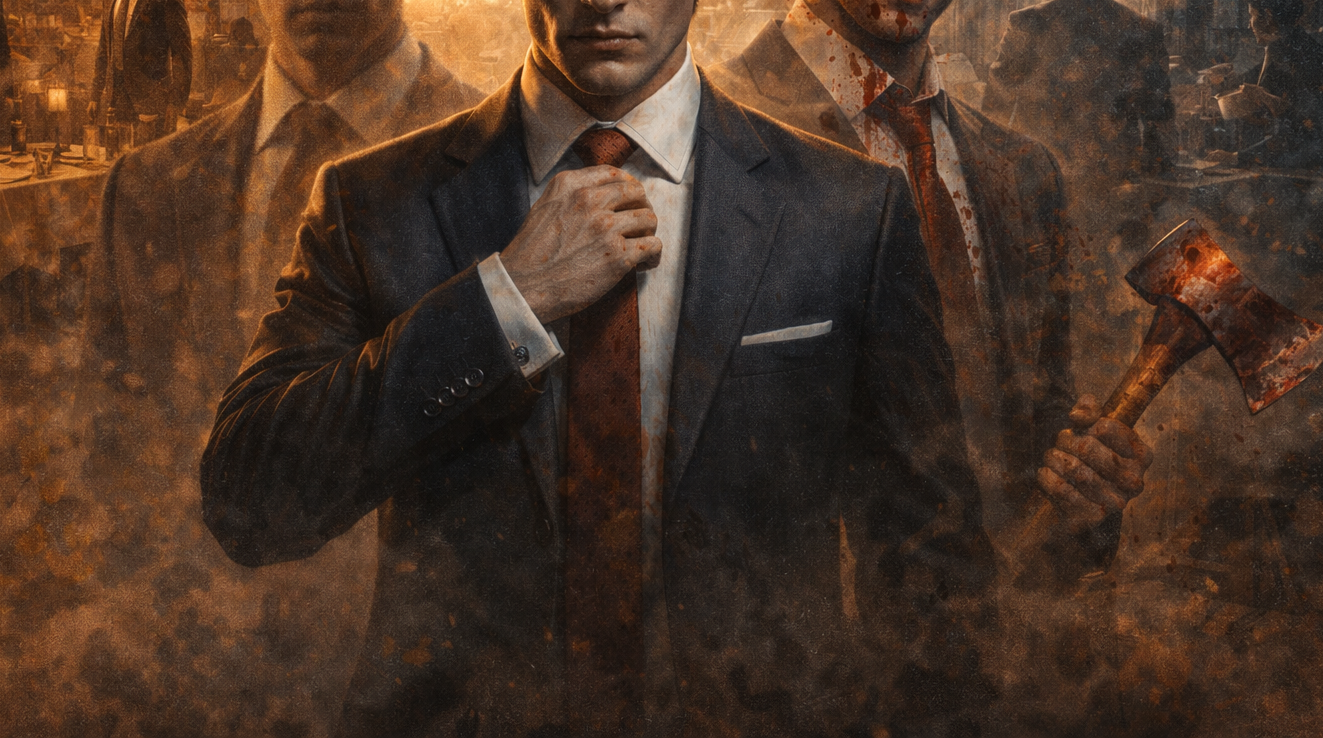

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis Summary

A Status Mask That Starts to Slip

Patrick Bateman looks like the finished product. The right suit. The right haircut. He makes the perfect restaurant reservations. The right opinions, delivered like a menu.

However, the life he leads is fragile. One wrong detail, the wrong name, or the wrong table, and he can feel himself drop out of the picture.

So he tightens his grip. On routines. On appearances. The focus is on other individuals.

This novel turns on whether Bateman can keep the mask intact when nobody can tell him apart from the other men wearing it.

The Promise

By the end, you will understand what Bateman is chasing, what he fears, and why the story keeps tightening around a question the book refuses to make comfortable: how much of what he does is “real”, and how much is the logical end of a life built on image.

You’ll also see why the most unsettling part is not the violence. It’s the ease with which a whole system keeps moving as if nothing happened.

Key Takeaways

A life built on being seen can still feel invisible. When your worth depends on taste and status, you start living like a product in a window.

Status competition does not stay polite. Small humiliations stack up, and the need to “win” turns into a need to dominate.

People become props when empathy becomes inconvenient. Once everyone is reduced to a label, cruelty stops feeling like a crossing of a line.

Confession is not always a bid for truth. It can be another performance, designed to control the room or test what the room will tolerate.

If nobody can tell you apart, you stop believing you exist. Bateman’s identity crisis is not a mystery to solve. It is the engine.

The city’s indifference is not passive. It rewards surfaces and punishes mess, so the easiest survival strategy is to look away.

Routine can become a hiding place. Obsession with self-improvement and “discipline” can mask decay rather than prevent it.

Modern life still tempts people to curate a self that is smoother than reality. The gap between the image and the person is where damage grows.

The Plot

Set-up

Patrick Bateman is a young, wealthy professional in late-1980s Manhattan, surrounded by men who dress alike, speak alike, and chase the same markers of prestige. Their conversations orbit restaurants, clothes, reservations, and the correct cultural signals, less as enjoyment and more as proof of belonging.

Bateman plays the game intensely. He polishes himself into a showroom version of a man. He also carries a simmering disgust: for strangers, for colleagues, for women, for anyone he can categorise as lesser, and for the fact that his own uniqueness never seems to register.

Inciting Incident

The early pressure is not a single event so much as a pattern of slights that Bateman experiences as threats to his existence. Being mistaken for other people becomes a recurring cut. He cannot anchor himself in how others see him, because they do not see him clearly at all.

In that atmosphere, his private impulses become sharper and darker. His inner world starts to split away from his public one, as if he is trying to prove, to someone, that he has weight.

Rising Pressure

Bateman’s social circle keeps feeding the same hunger: more exclusivity, more recognition, more proof. The stakes of trivial things rise because there is nothing else holding them together.

He fixates on a colleague, Paul Owen, who represents the kind of effortless status Bateman wants. Owen’s success, his confidence, even his presence in the room, reads to Bateman as an insult.

Bateman’s relationships are transactional and unstable. He has a fiancée, Evelyn, but the connection is thin, performed. He moves through encounters with a predatory detachment, as if other people exist to confirm his control.

As his aggression escalates, the boundary between what he does and what he imagines becomes harder to pin down. The narrative starts to feel like a mind trying to outrun itself.

The Midpoint Turn

Bateman acts on his fixation with Paul Owen. After that, he behaves like someone who expects consequences, and like someone who cannot quite find them.

This is where the novel’s central unease locks in. If Bateman has crossed the line he believes he has crossed, why does the world around him remain so smooth? Why do the usual mechanisms of accountability fail to bite? And if he has not crossed it in the way he claims, what does that say about his need to believe he has?

Either way, the pressure intensifies, because Bateman cannot return to a normal he no longer trusts.

Crisis and Climax

The story moves towards exposure without giving the listener the relief of a clean chase. There are investigations and suspicions circling the edges of his life, but Bateman’s environment is designed to absorb mess. People are distracted, self-absorbed, and invested in not making a scene.

Bateman, meanwhile, becomes more erratic. He tests reality with acts that feel like dares. He pushes, harder and harder, to see if anyone will stop him, recognise him, or name what he is.

At the peak, the novel creates a sense of spiralling: a man trying to force the world to acknowledge him, and finding that the world’s indifference may be stronger than his confession.

Resolution

Bateman attempts something like a confession, or at least the performance of one. He admits to actions that should detonate his life.

Instead, the response he gets is not judgement. It is confusion, dismissal, and the sense that even this can be absorbed as noise.

The closing movement is bleak in a specific way. Bateman is not redeemed. He is not cleanly condemned. He is returned to the same loop he began in: an environment that prizes surfaces, a self that cannot stabilise, and a hollow certainty that nothing he does will become an exit.

The Insights

A man built out of brand signals

Bateman’s personality is a stack of correct choices. He speaks in verdicts about what matters, what’s fashionable, what counts as taste. The performance is so constant it starts to look like the only part of him that exists.

That’s why misrecognition hurts so much. If you are the suit, the haircut, the reservation, then being mistaken for someone else is not a minor mistake. It’s erasure.

A concrete example sits in how often the men around him blur together. Names slip. Faces are interchangeable. Bateman’s terror is that he is not a person among people. He is one more product on the shelf.

The cost is that he cannot reach for a real self without admitting he has been empty.

The business-card war is not a joke

There are moments in this book where status competition becomes almost absurd, like a ritual where everyone pretends it’s casual while treating it as life or death.

Bateman does not treat these moments as comedy. He treats them as proof that the whole world is a ranking system, and that being outranked is a form of humiliation.

One famous pressure point is the obsessive comparison of small symbols of professional identity. The differences are tiny, but the emotional impact is huge, because they are fighting over meaning in a life that provides none.

The consequence is escalation. When the stakes are manufactured, you keep needing bigger wins to feel real.

Violence as a bid for existence

Bateman’s brutality is not framed as a single secret. It’s framed as part of a widening split. The more controlled his surface becomes, the more chaotic his private world grows.

There is a repeating dynamic: he feels slighted or unseen, he spirals, and he reaches for an act that will make him feel powerful and undeniable.

The novel repeatedly shows him using other people as objects in this struggle. They are not met as full humans. They are met as opportunities to prove dominance.

The cost is obvious and horrifying for his victims. The cost for Bateman is that even violence does not give him a stable identity. It gives him only momentum.

The city that refuses to notice

One of the most unsettling forces here is not Bateman himself. It’s the social environment that makes it possible for him to move without being stopped.

People are distracted. People are self-involved. People have incentives to avoid trouble. If a story is inconvenient, they downgrade it.

You see this in how suspicion glances off him. Even when something feels wrong, the social reflex is to keep the evening smooth, keep the conversation light, keep the world tidy.

The consequence is a kind of moral insulation. In a place where appearance is everything, reality becomes optional.

Confession as another mask

Bateman’s “truth” does not arrive as a clean reveal. It arrives tangled: part guilt, part boast, part test.

When he tries to admit what he has done, it does not land like a confession in a courtroom. It lands like something people can misunderstand, ignore, or reinterpret as exaggeration.

A key example is the way his admissions fail to create a decisive response. The world does not pivot. The system does not freeze. People do not suddenly see him.

The cost is that even honesty, if it exists here, is swallowed by performance culture.

When everyone looks the same, cruelty travels easily

Bateman’s circle is full of men chasing the same thing: prestige without friction. Their sameness is not just aesthetic. It is moral. It makes it easy to treat others as disposable, because disposable is how they already treat themselves.

The novel uses misidentification as a pressure mechanism. If any of these men can be swapped for another, then accountability becomes slippery. Even truth becomes slippery.

You can feel it in the way Bateman navigates spaces where nobody is fully present. People listen just enough to reply. They see just enough to judge. They do not connect.

The consequence is a world where harm can happen in plain sight and still be treated as a rumour.

The Engine

American Psycho runs on a loop: status anxiety creates self-erasure, self-erasure breeds rage, and rage looks for an outlet that feels absolute.

Bateman keeps forcing change because he cannot tolerate being ordinary, and his world keeps raising the stakes because it offers him no deeper measure of worth than surface approval.

He stays trapped because the mask is both his protection and his prison. If he drops it, he vanishes. If he keeps it, he rots inside it.

What This Looks Like in Real Life

A junior banker in a big-city office builds a life around “being the one who belongs”. Old approach: copy the right look, the right tastes, the right conversations, and treat any slip as disaster. New approach: pick a few non-negotiable values and let them guide choices, even when it costs status points. Consequence: fewer rooms open instantly, but the person stops living in panic over being found out.

A manager in a high-pressure workplace starts measuring everything that can be measured, including people. Old approach: performance becomes the whole relationship, and empathy is treated as inefficiency. New approach: keep standards high, but create a space where hard truths can be said without humiliation. Consequence: fewer “wins” that look good on paper, more trust, and fewer quiet collapses behind closed doors.

A young professional curates an online identity that is cleaner than their actual life. Old approach: polish every signal, hide every weakness, chase validation that never quite lands. New approach: present less, connect more, and stop outsourcing self-worth to the feed. Consequence: slower attention, but more stable confidence, and less temptation to treat others as props.

A Simple Action Plan

Where do you feel most replaceable, and what do you do to hide that feeling?

What status symbol do you chase that never actually satisfies you?

When have you mistaken “discipline” for fear of being seen?

Which relationships in your life run on performance rather than truth?

What is one place you keep smoothing over reality to keep things comfortable?

When you feel slighted, what is your default move: withdraw, retaliate, or prove yourself?

If you stopped trying to be impressive for a month, what would you build instead?

Conclusion

American Psycho traps you inside a life where image is oxygen and identity is always about to be revoked. Bateman is not simply hiding a secret. He is trying to manufacture a self in a world that keeps telling him he is interchangeable.

The story’s final damage is that nothing cleansly breaks. No grand reckoning arrives to reset the moral balance. Bateman’s actions, his admissions, and his spiral all fold back into the same environment that shaped him, leaving him stuck with the one thing he cannot stand: the sense that he cannot be truly known.

If you want more episodes like this, follow the show on Spotify so you never miss the next deep dive. And find the written version and extras on [WEBSITE_NAME].

Some stories end with closure. This one ends with a room full of people still talking.

Relevance Now

This novel hits a nerve because modern life still rewards surfaces that travel well. Online identity, performance culture, and status anxiety can turn into a quiet arms race where the goalposts keep moving and nobody admits they are scared.

Bateman’s world runs on signals and scarcity: who gets in, who gets seen, who counts. That maps cleanly onto workplaces where metrics become identity, and onto digital spaces where attention becomes a proxy for worth. When recognition is brittle, people reach for extremes to feel undeniable.

The book also mirrors loneliness in hyper-connection. Bateman is surrounded, yet functionally alone, because genuine contact would require him to be a person instead of a product.

Watch for the moment you start treating other people as an audience rather than as humans. That is where the slide begins.

A culture that cannot recognise a person will eventually reward a mask.