Orbital Book Summary: The Perspective Shift That Changes How You See Earth

Cold Open

Six people float through a day that never sits still.

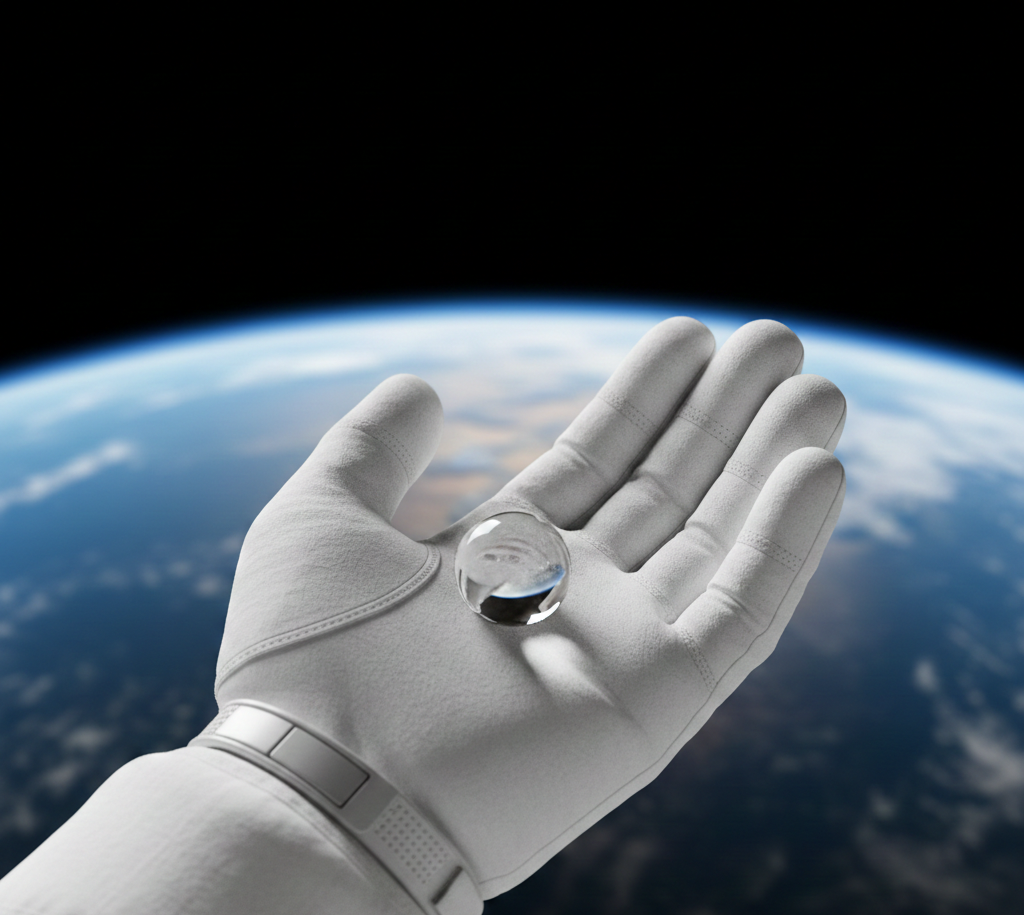

Outside their windows, Earth keeps turning. Oceans roll like dark silk. City lights bead along coastlines. Weather swirls, then breaks apart, then gathers again.

Down on the ground, life feels solid and urgent. Up here, everything looks fragile. Even time.

This book turns on whether distance makes us numb, or makes us responsible.

The Promise of the Book

Orbital is a small, intense novel set in the thin corridor between Earth and the rest of the universe. It places a handful of astronauts on a space station and lets a single stretch of time do the work a big plot usually does.

The promise is simple and sharp. If you change the viewpoint, you change the meaning. The planet becomes one object. The people become one species. And the things you thought were permanent start to look temporary.

The stakes are human. How do you live well when you can see, in one glance, how brief and shared everything is?

Key Takeaways

Attention is the real drama. In orbit, the biggest shift is not what happens, but what gets noticed, and what can no longer be ignored.

A borderless Earth rewrites the story. When lines vanish from view, ideas like “ours” and “theirs” start to feel like habits, not laws.

Time becomes a loop. Repetition can dull the mind, or it can polish it, depending on how you meet it.

Beauty carries pressure. Seeing the planet as luminous and delicate does not soothe guilt. It can sharpen it.

The body is a reminder of limits. Even in the most advanced setting imaginable, humans still need sleep, care, routine, and each other.

Home follows you. Memory, grief, longing, and love do not stay on Earth. They travel.

Perspective can be a tool, not a mood. You do not need space to practise a wider view. You need a method.

The Core Thesis

At its core, Orbital uses the space station as a lens for a single question: what changes when you look at Earth from far enough away to see it as one thing?

The novel’s engine is contrast.

Up there, the planet looks whole. Down here, it is divided by stories, systems, and daily pressures. Up there, time is measured in repeated passes and strict routines. Down here, time is felt as deadlines, seasons, birthdays, and loss. Up there, the view is vast. Down here, the view is narrow, because it has to be, just to get through the day.

The book does not argue like an essay. It works by immersion. It lets the reader drift alongside the crew, watching the same world again and again, until the repetition becomes a kind of truth.

“Orbital” is not just a place. It is a way of thinking. A loop that forces the mind to return to the same object, and ask, each time, what it really is.

The Big Ideas

A day can be a universe

A single day in orbit contains a strange abundance. There is routine, yes. There is work, yes. But there is also the constant shock of the view, the constant recalibration of scale.

The book suggests that “nothing happens” is often a lie we tell when we do not know how to name what is happening inside a mind.

So what? It reframes boredom and repetition as raw material. Not a dead zone, but a place where meaning can be made.

Earth looks calm even when it isn’t

From space, the planet can look serene. Clouds soften the edges. Oceans hide their violence. Night makes everything gentle.

But the calm is visual, not moral. The book holds that tension. The view can be beautiful while the reality is harsh. It can be breathtaking while it contains suffering.

So what? It challenges the instinct to confuse “looks fine” with “is fine,” in politics, in relationships, and in your own life.

Borders are stories, not features

Orbit strips away the map you were taught. Nations do not announce themselves. Ownership does not show up in the colours of the land.

This is not a naive claim that conflict disappears if you stop looking at lines. It is a reminder that many “facts” are agreements. They can be changed, because they were made.

So what? It pushes a listener to ask which parts of their world are laws of nature, and which are habits with uniforms.

The body is the anchor

Space is often sold as escape. Orbital leans the other way. It keeps returning to the needs of a human body in an unnatural environment.

Even here, the basics rule. Sleep matters. Food matters. Small pains matter. Fear matters. The body will not be impressed by ambition.

So what? It quietly undermines the fantasy that a new context will fix you. You bring yourself everywhere, including your limits.

Isolation can sharpen intimacy

A small crew in a sealed habitat has nowhere to hide from other people, or from themselves. Private life becomes porous. Silence becomes louder.

The book treats this as both tenderness and strain. Connection is real, and so is fatigue. A few voices can feel like a lifeline and a cage.

So what? It offers a clean lens for life on Earth. Many of us live in smaller “stations” than we admit: teams, families, flats, online spaces. The question is how we behave when the walls do not move.

Awe is not comfort. It is a demand.

Awe is usually packaged as healing. Here, awe has teeth.

To see the planet as luminous and thin, hanging in blackness, is to feel love and dread at once. The view can enlarge the heart. It can also enlarge guilt. It can make the small cruelties of daily life feel obscene.

So what? It suggests that wonder is not a holiday from ethics. It can be the starting gun.

The planet is both home and stranger

The more you stare at Earth, the less it behaves like a background. It becomes an object, a creature, a single living system that does not care about your plans.

That shift is unsettling. Home should feel familiar. But in orbit, home can look alien. Not because it has changed, but because your angle has.

So what? It proposes a powerful mental move: treat what you take for granted as if you are seeing it for the first time.

The Best Evidence and Examples

The strongest “evidence” in Orbital is experiential. The novel keeps circling a few vivid anchors and letting them deepen.

First, the repeated passes over the same world. The crew sees day and night in fast alternation, and that rhythm becomes the book’s pulse. It is hard to cling to a single mood when the planet keeps changing its face.

Second, the ordinary tasks set against the extraordinary view. Work continues. Procedures continue. The day is structured. And all the while, Earth is right there, turning like a reminder you cannot switch off.

Third, the crew’s private memories alongside the shared spectacle. The book suggests that even the most extreme setting cannot erase the human interior. The mind still returns to people, places, regrets, and hopes.

Fourth, the silence of space itself. The vastness outside the station is not romantic. It is indifferent. That indifference throws the value of the small, warm, breathable world into sharper relief.

Tensions, Blind Spots, and Pushback

Some readers will find Orbital exhilarating. Others will find it slippery.

One tension is plot. If you come looking for a conventional chain of events, this book may feel like it resists you. It is more concerned with perception than with surprises. That can feel profound, or it can feel withholding, depending on what you want from fiction.

Another tension is the risk of turning orbit into a moral podium. A “space view” can slide into easy sermons: we are all one, so why can’t we act like it? The book’s strength is that it often avoids that simplification. Still, a sceptical reader might argue that seeing unity does not automatically build the systems needed to live it.

There is also a question of who gets to have this view. The space station is a rare place. The experience is elite by definition. A critic could say that the book flirts with the idea that clarity comes from distance, when many people on Earth have clarity forced on them by hardship, not by altitude.

And finally, there is the emotional wager. The novel asks you to care about shifts in attention as if they are events. If you accept that wager, the book can feel electric. If you do not, it can feel like beautiful weather passing over glass.

What This Changes in Real Life

Imagine a manager in London running a team that feels permanently frantic. They read Orbital and steal one idea: the day is not a straight line. They stop scheduling everything as if it is a race. They build in deliberate loops: weekly resets, shorter meetings, a clean handover ritual. The team does not become perfect. But the pace becomes survivable.

Now picture a student in Toronto who feels trapped inside one identity. One subject. One plan. The book’s view loosens that grip. They start treating identity as something that can orbit, not something that must lock into place at nineteen. They choose breadth for a year. They do not waste the year. They widen it.

Take a founder in Nairobi who lives online, always reacting. The book’s quiet pressure makes them notice how rarely they see the whole picture. They introduce one “wide view” practice: once a week they step away from dashboards and ask, in plain language, what problem they are truly solving for real people. The product changes slightly. The culture changes more.

And consider a nurse in Manchester coming off night shifts, exhausted and bitter. The book does not fix that. But it offers a different frame. The nurse starts taking ten minutes before sleep to watch the sky, not for inspiration, but for scale. The job is still hard. The anger still shows up. But it no longer owns the whole mind.

A Simple Action Plan

Step 1: Build a daily “orbit” moment. Choose a fixed time and spend two minutes looking outward. Sky, tree line, rooftops, clouds. No phone. The point is repetition.

Step 2: Practise the borderless view once a week. Pick one issue that makes you tribal. Politics, sport, class, status. Then describe it as if you were explaining it to someone who cannot see borders. Keep it honest. Keep it simple.

Step 3: Separate beauty from comfort. When something is moving or lovely, notice the urge to treat it as permission to relax. Then ask one clean question: what does this beauty ask of me?

Step 4: Put your routines next to your values. List your most repeated actions in a normal week. Then name the value each action serves. If an action serves no value and drains you, it is a candidate for removal.

Step 5: Treat “nothing happened” as a signal. Once a day, write one sentence about what changed inside you. Not what happened outside. Just the internal shift. This is how you train attention to register meaning.

Step 6: Make one small repair. Pick a repair that fits your scale: apologise, recycle properly, pay the invoice on time, message a friend, tidy a corner, donate, vote, rest. The book’s view can feel huge. Ground it in one act.

Step 7: Protect your sleep like oxygen. If the novel leaves you with anything practical, it is respect for the body. Choose one small sleep boundary and keep it for a week.

Conclusion

Orbital takes the oldest human dream, leaving Earth, and uses it to show a newer problem: we live inside a world we rarely see clearly.

Its power is not in spectacle. It is in attention. It insists that the planet is not a stage set behind our lives. It is the main character. And we are temporary, bright, anxious passengers moving across its surface.

The book’s final pressure is simple. If you could see Earth as one thin, shared home, what would you stop pretending not to know?