To Kill a Mockingbird – Summary and Analysis

A young girl watches her father stand alone against a town’s anger.

A Black man sits in a courtroom, fighting for his life against false charges. These scenes could be headlines today as much as they are pages from a classic novel. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, though set in the 1930s, feels fiercely relevant in our modern era.

At a time when society is still grappling with racial injustice and even debating the teaching of this very book in schools, To Kill a Mockingbird stands as a powerful reflection of conscience and compassion.

Lee’s novel, published in 1960, is more than just a story from the past – it’s a mirror held up to today’s struggles. With sharp, simple prose and unforgettable characters, the book forces readers to confront hard truths about prejudice and moral courage. It remains a staple in classrooms and a lightning rod in cultural conversations.

In the face of current events – from courtroom controversies to clashes over banned books – To Kill a Mockingbird offers a lesson on empathy and justice that is as urgent now as it was over sixty years ago.

Key Points

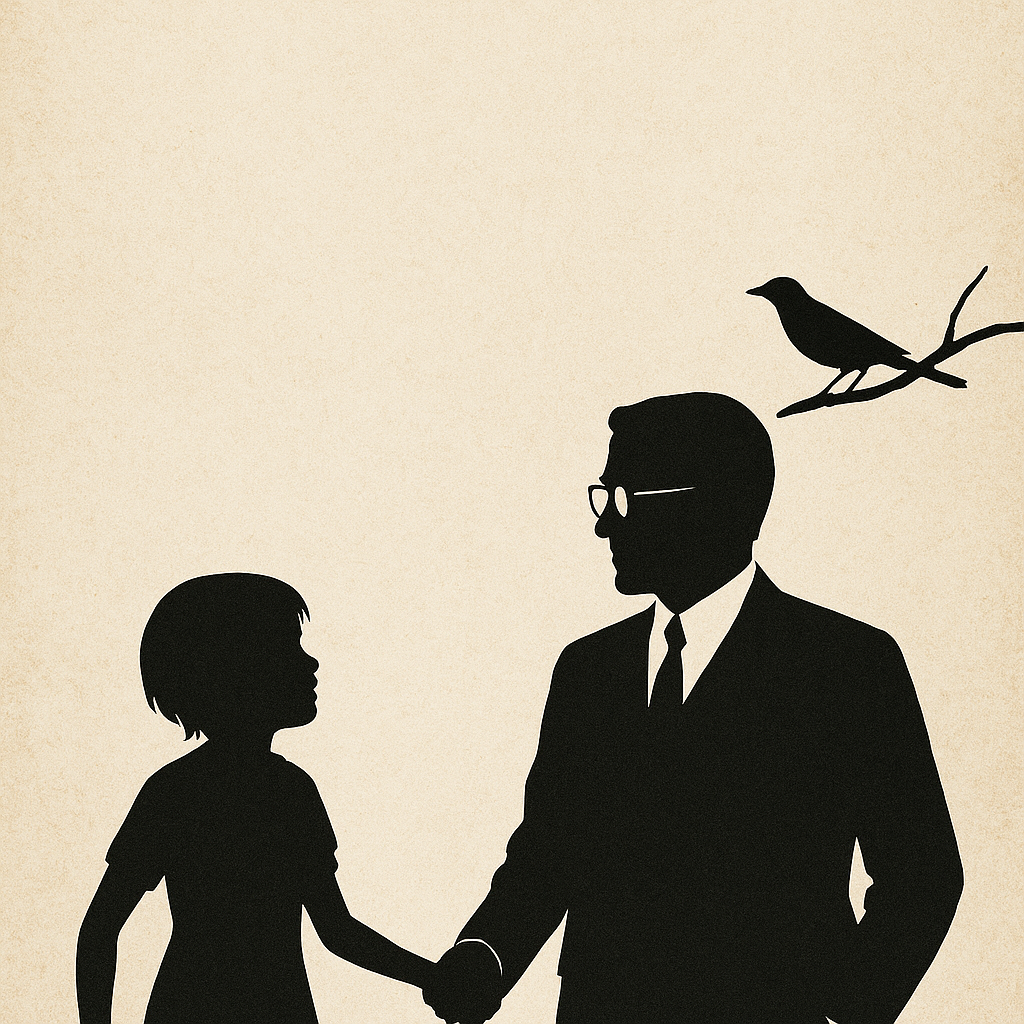

Story Setting and Plot: To Kill a Mockingbird takes place in a small Alabama town during the Great Depression (1933–1935). It follows Scout Finch, a curious six-year-old girl, as her widowed father Atticus Finch, a principled lawyer, defends Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused of raping a white woman. The trial and its aftermath expose the town’s deeply ingrained racism and test the integrity of those involved.

Characters and Perspective: The narrative is told through Scout’s eyes, blending the innocence of childhood with the reflection of an adult narrator. Scout, her older brother Jem, and their summer friend Dill explore mysteries like their reclusive neighbor Boo Radley while learning harsh realities about their community. Atticus Finch emerges as a model of conscience and courage, teaching his children to consider things from others’ points of view and to stand up for what’s right, even when he faces scorn from neighbors for defending Tom.

Major Themes: The novel explores racial injustice, moral growth, and the loss of innocence. It portrays how prejudice can poison a community – Tom Robinson’s conviction despite clear evidence of his innocence exemplifies the failure of justice under racism. Another key theme is empathy: Atticus’s guiding principle is that “it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” symbolizing the wrongness of harming the innocent. Both Tom Robinson and the shy Boo Radley are likened to mockingbirds – innocents who are misjudged or mistreated by society.

Historical Context and Impact: Written amid the early Civil Rights Movement, the book reflects real Jim Crow-era injustices. It alludes to events like the Scottsboro Boys trials of the 1930s (where Black youths were falsely accused of crimes) and echoes the segregated social order of its time. Upon its 1960 publication, To Kill a Mockingbird became an instant success, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1961. It has since sold over 40 million copies worldwide and remains a classic of American literature. For decades, it has been widely taught in schools as a lesson against prejudice and a beacon of moral literature.

Cultural Relevance: To Kill a Mockingbird endures because it challenges readers to examine their own sense of justice. Atticus Finch’s character has influenced generations of readers and even lawyers, embodying integrity and fairness. In today’s climate, the novel sparks discussions about race, fairness, and who gets to tell stories of injustice. Its presence on reading lists is sometimes controversial – the book has faced bans or challenges due to its frank language and racial themes – yet its message of empathy and courage continues to resonate and inspire important conversations.

Background

To understand To Kill a Mockingbird, it’s crucial to know the world that shaped it. The story is set in Maycomb, Alabama, during the Great Depression. In the 1930s Deep South, racial segregation and Jim Crow laws were a harsh reality. This was a time when an accusation against a Black person could lead to a lynch mob at the jailhouse door. Harper Lee drew from this historical backdrop – she grew up in Alabama and witnessed the ingrained prejudices of small-town life. The fictional trial of Tom Robinson parallels real trials of that era, such as the notorious Scottsboro Boys case in 1931, where nine Black teenagers were falsely accused of raping two white women. Those events highlighted the systemic racism in the justice system, and Lee channeled that truth into her novel’s core conflict.

When Harper Lee wrote the book in the late 1950s, the United States was on the cusp of the Civil Rights Movement. The novel was published in 1960, the same era as bus boycotts and rising calls for equality. Its release was timely: Americans were beginning to reckon with the legacy of racial injustice, and Lee’s story struck a national nerve. Despite its Southern Gothic setting, readers across the country saw reflections of their own society in the trial’s unfairness and the community’s biases. The character of Atticus Finch was partly inspired by Lee’s father, a lawyer who had once defended Black clients in court. Through Atticus, Lee honored those who upheld justice in an unjust time. The book’s background, therefore, blends personal experience with historical reality – giving it authenticity and emotional weight.

Over the years, To Kill a Mockingbird became more than just a popular novel; it turned into a cultural touchstone. It never went out of print, a testament to its enduring relevance. By the 21st century, nearly every American student encountered the book in school. This widespread readership means the story has influenced millions, shaping discussions about race and morality for generations. Understanding the backdrop – the 1930s Southern world of the story and the 1960s atmosphere of its publication – helps explain why the novel remains so powerful. It was born out of a specific historical moment of injustice and hope, yet it speaks to universal ideals of justice, decency, and understanding that continue to matter today.

Plot and Character Analysis

Plot Overview: To Kill a Mockingbird unfolds through a series of events in young Scout Finch’s life, over the span of about three years. In the beginning, Scout (Jean Louise Finch) is a precocious six-year-old in Maycomb, a sleepy town still reeling from the Depression. She lives with her older brother Jem and their father Atticus, who is a respected lawyer and single parent. Through Scout’s eyes, we meet neighbors and hear town gossip, which sets a light, sometimes humorous tone despite serious undercurrents. Scout, Jem, and their friend Dill are especially fascinated by the local mystery man, Arthur “Boo” Radley, a recluse whom neighborhood legends describe as a ghostly, dangerous figure. The children play games imagining Boo’s life and even dare each other to approach the Radley house, demonstrating childhood innocence and superstition. Over time, small kind gestures – like gifts left for them in the knothole of a tree – hint that Boo may be quietly watching and caring for them, belying his scary reputation.

The Trial of Tom Robinson: The heart of the novel is the trial of Tom Robinson. Atticus Finch is appointed to defend Tom, a Black field hand accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a young white woman from a disreputable family. This decision sets the town ablaze with talk – many white residents are angered that Atticus would earnestly defend a Black man. Scout and Jem feel the impact: kids at school and even some adults insult Atticus as a “nigger-lover” for his stance. Despite the scorn, Atticus stands firm in his principles, calmly explaining to his children why every person deserves a fair defense. In one tense scene before the trial, a lynch mob gathers at the jail intending to kill Tom. Atticus, alone, sits outside reading by the light to guard his client. When Scout, Jem, and Dill inadvertently interrupt this standoff, Scout’s innocent conversation with one of the mob’s men shames the crowd into dispersing. This moment shows how the innocence of a child momentarily pricks the conscience of biased adults, diffusing violence with simple humanity.

The trial itself is a gripping drama that exposes Maycomb’s racial prejudices. In the courtroom, with Scout and Jem secretly watching from the segregated balcony, Atticus presents a powerful defense. Through evidence and cross-examination, he reveals that Mayella Ewell’s story is false. The truth emerges that Mayella likely approached Tom Robinson herself and was then beaten by her own father, Bob Ewell, when he caught her. Tom’s left arm is crippled from a past accident, making it nearly impossible for him to inflict the injuries Mayella sustained (which suggest a left-handed attacker – and Bob Ewell is left-handed). Despite these facts and the clear reasonable doubt, the all-white jury delivers a guilty verdict. The outcome devastates Jem, who had believed justice would prevail. For Scout, it’s a confusing and formative moment – she sees goodness in her father’s fight, yet witnesses the community’s injustice triumph. The guilty verdict is a poignant illustration of the novel’s central theme: how deep-seated racism can corrupt the moral logic of a society. Not even an impeccable defense by Atticus can overcome the prejudices that blind the jurors.

Characters and Themes: The characters of To Kill a Mockingbird each illuminate different facets of the social fabric. Atticus Finch stands at the novel’s moral center. He is portrayed as a quietly heroic figure – a man of high integrity and empathy. Atticus teaches Scout and Jem compassion through both words and example. He famously tells them “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view…until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” He lives this lesson by defending Tom Robinson. Atticus knows that taking Tom’s case will make him unpopular and even put his family at risk, yet he does it because his conscience demands it. His steady courage and courtesy, even towards hateful antagonists like Bob Ewell, exemplify the ideal of justice tempered with empathy. Many readers view Atticus as a model of what a good person – and especially a good lawyer or public servant – should be. Through Atticus, the book shows that true bravery isn’t a man with a gun, but someone who stands up for what is right even when the odds are against him. (In one subtle scene, Atticus shoots a mad dog threatening the town, revealing to his children that he has skill with a rifle but had never boasted of it. This becomes a metaphor: real courage is not shown through violence or pride, but through moral strength.)

Scout and Jem undergo significant growth, making this story a classic Bildungsroman (coming-of-age tale) as well as a social commentary. Scout starts off as an impulsive, naive child who eagerly believes gossip and reacts hot-headedly to insults. Over the course of the book, she learns to restrain her fists, using her mind and heart instead. She observes the hypocrisy and kindness in her community and begins to discern right from wrong beyond just what adults say. Jem, who is a few years older, faces a loss of innocence more directly. The trial’s outcome shatters Jem’s trust in the goodness of his neighbors and the fairness of the law. He moves from childhood optimism to a more jaded understanding: that people can be unfair and cruel despite appearing respectable. Their experiences signify the destruction of innocence – a major theme – but also highlight the importance of how they respond to that loss. Under Atticus’s guidance, the children learn not to become cynical or hateful, but to hold onto conscience and empathy.

One of the novel’s most symbolic storylines is that of Boo Radley. Boo is a recluse who lives down the street, and at first he’s an object of spooky fascination for Scout, Jem, and Dill. Neighborhood lore casts Boo as a “monster” who never steps outside. However, Boo’s unseen presence is felt throughout the story in gentle ways – he leaves little presents for the children (like carved soap figures and candy) and quietly watches over them. In the climactic scene after the trial, when Bob Ewell seeks drunken revenge by attacking Scout and Jem in the dark, it is Boo Radley who emerges from his house to save them. He overpowers Ewell, and Bob Ewell ends up dead in the struggle. For the first time, Scout meets Boo face to face – discovering he is not a monster at all, but a pale, shy man who cares deeply for her and Jem. Sheriff Tate and Atticus decide to protect Boo’s privacy by saying Ewell’s death was an accident (the sheriff insists Bob fell on his own knife). They know dragging the timid Boo into the spotlight of a legal inquiry would be cruel – like killing a mockingbird. As Scout walks Boo home and then stands on his porch, she finally sees her neighborhood from Boo’s perspective. In that moment, she fully grasps her father’s lesson about empathy. Boo’s character arc reinforces the theme that people often fear and slander what they don’t understand. Yet, those very outsiders or innocents (the “mockingbirds”) may turn out to be the best among us if we take the time to see them truly.

Themes and Real-World Implications: The interplay of these characters and plotlines drives home several powerful themes. Racial injustice is the most prominent: Tom Robinson’s fate demonstrates how racial bias can lead to the condemnation of an innocent man. The fact that Tom, after being wrongly convicted, is killed during an attempt to escape custody underscores the tragedy – a good person destroyed by an evil system. This theme invites readers to question how far society has come (or not) in treating people fairly regardless of race. Another theme is moral courage – epitomized by Atticus and echoed in smaller acts by others (for instance, the few townsfolk like Judge Taylor and Sheriff Tate who quietly support fairness, or Miss Maudie, the neighbor who defends Atticus’s choices). The novel suggests that doing what is right is not always rewarded, but it is necessary for social progress.

The loss of innocence ties into how both the children and the community confront reality. Maycomb’s facade of a friendly, polite town is shattered by the ugly racism beneath its surface. Jem’s disillusionment and Scout’s awakening reflect a broader message: a society’s innocence is lost when it confronts injustice, but that loss can lead to greater understanding. Empathy and understanding are offered as the antidote to prejudice. Nearly every conflict in the story – whether it’s the children’s fear of Boo or the town’s treatment of Tom – stems from people not seeing others as fully human. By the end, Scout’s ability to imagine herself in Boo Radley’s shoes stands as a triumph of empathy over ignorance.

In terms of geopolitical and social angles, the novel, while local in its story, mirrors America’s broader racial tensions. Maycomb is a microcosm of the American South, with its strict social hierarchies and unspoken rules about race and class. The trial and its verdict reflect how law and politics were influenced by racism – a reality not confined to one small town. The book subtly comments on the Great Depression’s impact as well: poverty crosses racial lines (the Ewell family is white but impoverished and pitied by no one, showing that class prejudice exists alongside racial prejudice). By including characters like Calpurnia (the Finches’ Black housekeeper who is educated and nurturing) and Aunt Alexandra (Atticus’s sister who is preoccupied with family name and status), the story also touches on internal social stratifications and the clash between traditionalism and conscience.

Why This Matters

Why does To Kill a Mockingbird still matter today? First, its core lessons about justice and empathy remain profoundly relevant. The novel asks readers to step into someone else’s shoes – whether it’s a wrongly accused Black man or a misunderstood recluse – before making judgments. In an era where divisions along racial, economic, or political lines still run deep, that message is a vital reminder of our shared humanity. The story encourages a stance of understanding rather than fear or hatred. This perspective is essential for a healthy society, especially as we navigate contemporary debates around equality and human rights. Reading the novel today, one can’t help but draw parallels between Tom Robinson’s trial and present-day situations where bias and inequality are at play. It prompts tough but necessary questions: Are we fair to those who are different from us? Do we stand up, like Atticus, against popular opinion when we know something is wrong?

There are also social and educational consequences tied to the novel, which highlight its importance. To Kill a Mockingbird has been a fixture in education precisely because it confronts uncomfortable history in a way young people can grasp. By seeing events unfold through Scout’s young perspective, generations of students have learned about racism and moral integrity in a personal, relatable way. The discomfort some feel with the book’s language or content is actually part of its impact – it forces readers to feel the injustice and indignity that the characters experience. In a time when certain painful parts of history are sometimes glossed over or contested, the novel stands as an argument for honest reflection on our past. It matters because it doesn’t let us look away from the harm prejudice causes.

Politically and culturally, Atticus Finch’s example still resonates as well. His character teaches about the importance of the rule of law and ethical leadership. In the modern day, when public trust in institutions can waver, Atticus represents the ideal that lawyers, judges, or any officials should aspire to: unwavering ethics, service to truth, and compassion. Many legal professionals cite this fictional character as an inspiration for why they pursued law or how they approach justice. This speaks to the novel’s wider influence on American moral imagination. Moreover, To Kill a Mockingbird sparks dialogue—sometimes heated—about whose stories we value and how we address race in literature. Some argue about its perspective (for instance, that it centers on a white family’s view of racism), but even those debates underscore that the book matters enough to merit re-examination. In sum, the novel remains a catalyst: for empathizing with others, for educating young readers about right and wrong, and for inspiring discussions on building a more just society.

Real-World Examples

The themes of To Kill a Mockingbird are not confined to fiction; real life continues to offer examples that mirror the novel’s lessons. Consider the justice system today – there are still cases that evoke Tom Robinson’s ordeal. Wrongful convictions of innocent people (disproportionately people of color) come to light with distressing regularity, often decades later through DNA evidence or recanted testimony. Each time an innocent person is exonerated after being punished for a crime they didn’t commit, it’s a real-world Tom Robinson moment. It highlights how prejudice, or simply a rush to judgment, can destroy lives. For example, in recent years, headlines have told of Black men freed after long prison terms when evidence finally proved their innocence. These true stories echo the fictional trial in Maycomb, forcing communities to confront failures in fairness. They drive home the same point Atticus tried to make to that 1930s jury – that justice must be blind to race and grounded in truth, or else it isn’t justice at all.

Another example can be seen in the ongoing debates over the novel itself in schools. In some American school districts, To Kill a Mockingbird has been removed from reading lists or libraries. This usually happens because certain parents or officials worry that the book’s use of racial slurs or its subject matter will upset students. In one well-known instance, a school board said the novel “made people uncomfortable.” That very discomfort, however, is what sparks meaningful conversations. On the other side, many educators and readers push back against these bans, arguing that confronting the history of racism through literature is crucial for students’ understanding and empathy. This clash is playing out in real time: some classrooms quietly omit the book, while others hold it up as an essential teaching tool. The controversy itself is a practical example of the novel’s impact – even in 2025, a story about a trial in the 1930s can stir debate about how we deal with race, history, and free expression.

We also find everyday examples of empathy overcoming prejudice, much like Scout’s change of heart about Boo Radley. Think of diverse communities today where people make an effort to know their neighbors across cultural or racial lines. When individuals step outside of their social bubbles – perhaps through community programs, shared projects, or simple acts of kindness – misunderstandings often give way to human connection. For instance, police officers and youth in some neighborhoods have joined in dialogue programs to see life from each other’s perspectives, reducing mutual distrust. These real efforts mirror Scout’s revelation on Boo’s porch: when you finally see the world through another’s eyes, the fear and suspicion can fade. In workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods, whenever someone is no longer seen as “the other” but as a person with a story, we witness the novel’s principle in action. Society changes a bit for the better each time empathy replaces ignorance.

In conclusion, To Kill a Mockingbird provides timeless insights that are continually echoed in real life. From courtrooms to classrooms, from family discussions to national debates, the story’s call for justice and understanding remains deeply relevant. Whether we are reflecting on a wrongful conviction case, discussing which books children should read, or simply getting to know someone unlike ourselves, Harper Lee’s message endures: recognize the dignity of others, stand up for what is right, and never be afraid to show compassion. These lessons make To Kill a Mockingbird not just a summary of one girl’s childhood in the 1930s, but a guide for navigating the moral challenges of our own time.