Rachel Reeves, the Budget ‘Black Hole,’ and the OBR: Did the Government Mislead the Nation?

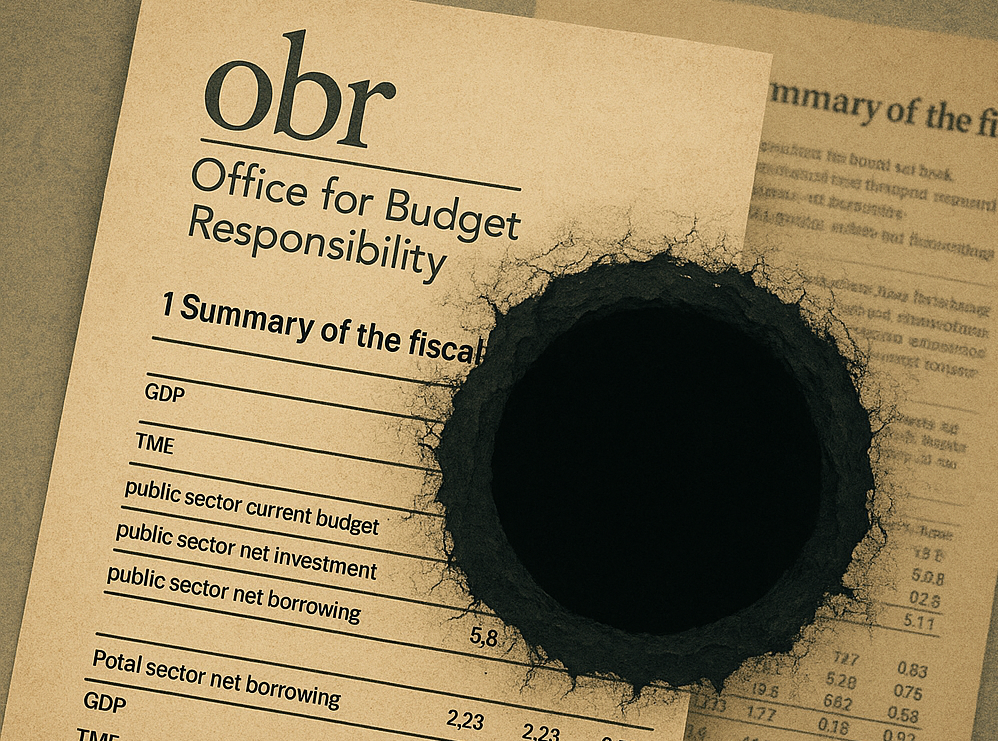

The row over Rachel Reeves’s recent Budget has turned into a wider crisis of trust. The UK chancellor is accused of misleading the country about a looming “budget black hole” to justify £26 billion in tax rises, even as official forecasts pointed to a small surplus rather than a gaping deficit. At the same time, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has been rocked by an embarrassing leak of its Economic and Fiscal Outlook, culminating in the resignation of its chair.

This dispute over the “Rachel Reeves budget black hole” is no longer just a fight about numbers. It has become a test of honesty in politics, the independence of fiscal watchdogs, and the credibility of a government that promised stability after years of turmoil. Critics say voters were scared with talk of a hole in the public finances that did not exist in the way implied; defenders insist Reeves still faced a tighter outlook and needed to act.

This article unpacks how the row began, what the OBR’s figures actually showed, why the leak matters, and how the clash between narrative and reality could shape both the government’s future and public faith in economic policy.

Key Points

Rachel Reeves framed her 2025 Budget around a large “black hole” in the public finances and pushed through about £26 billion in tax rises.

OBR documents later revealed that, before any policy changes, the government was heading for a small surplus and still met its main fiscal rule, not a dramatic shortfall.

The BBC’s political editor said the broadcaster felt misled by pre-Budget briefings, while opposition parties accused Reeves of lying to justify tax hikes.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has strongly defended the chancellor, arguing that weaker productivity, higher welfare costs, and the need for more “headroom” meant tough choices were unavoidable.

Separately, the OBR’s Budget forecast was accidentally published early due to website errors, described as the watchdog’s “worst failure” and leading to the resignation of its chair, Richard Hughes.

The combination of contested messaging and institutional failure has fueled calls for greater transparency, tighter rules on pre-Budget communications, and renewed scrutiny of the OBR’s independence.

Background

The Office for Budget Responsibility was created in 2010 to provide independent forecasts of the UK’s economic outlook and public finances. Its job is to stop governments from marking their own homework by setting out how fiscal plans affect debt, growth, and borrowing.

Rachel Reeves, the UK’s first female chancellor, has leaned heavily on the idea of responsibility and stability since entering the Treasury. She previously accused the former Conservative government of leaving a large hole in the public finances and promised to rebuild credibility with markets and international investors.

Her 2025 Budget, delivered in late November, came with two big political constraints. First, Labour’s manifesto pledge not to increase the basic, higher, or additional rates of income tax. Second, self-imposed fiscal rules that require debt to be falling as a share of GDP and current spending to be financed from tax revenues over a rolling period.

Ahead of the Budget, Reeves and colleagues spoke of a grim outlook. A review of the supply side of the economy by the OBR was expected to downgrade productivity growth, shrinking the space for new spending or tax cuts. The chancellor gave an early speech warning that the UK faced hard choices and repeatedly stressed that she would not duck those challenges.

By the time she stood up in the House of Commons to deliver the Budget, expectations had been carefully set: there was, she implied, a significant budget black hole to fill. When the OBR’s letter to Parliament later revealed that its pre-Budget forecasts actually showed a small surplus and intact fiscal targets, the political narrative began to unravel.

Analysis

The contested story of the ‘budget black hole’

At the heart of the dispute is a simple question: what did the OBR’s numbers really say, and how did that compare with the message voters heard?

The OBR’s forecasts evolved over several weeks. Early modeling suggested that weaker productivity would lower future tax revenues, worsening the budget position. But later runs incorporated higher inflation and stronger wage growth that, in turn, raised tax receipts. By the final pre-Budget forecast at the end of October, those effects had offset much of the damage, leaving a modest surplus and a reduced but still positive buffer against Reeves’s main fiscal rule.

In other words, the chancellor’s headroom had shrunk, but it had not vanished. She still met her rule that debt should be falling, though with less room for error. The OBR’s letter to the Treasury Select Committee laid out this timeline in unusually stark detail, an act the watchdog said was needed to “set out the facts” after days of political controversy.

Critics argue this undermines the dramatic language about a black hole that Reeves and her team used in the run-up to the Budget. They say voters were led to believe that a huge gap had opened up in the public finances, threatening manifesto promises and forcing the government into sweeping tax rises. Instead, they contend, the main driver of those rises was political choice: reversing welfare cuts, boosting public service funding, and building a bigger safety margin to reassure markets, rather than plugging an unavoidable gap.

Supporters counter that the distinction matters less than it seems. From their perspective, starting a Budget with less fiscal space, rising welfare demands, and pressure to raise defense spending amounts to a serious challenge, even if the headline deficit is not enormous. They argue that Reeves chose to move early, locking in tax increases while markets remain relatively calm and before further shocks could hit.

Political stakes for Reeves and Starmer

The political risk is sharp. Reeves and Prime Minister Keir Starmer came to power promising honesty, seriousness, and an end to chaotic fiscal policy. If the public comes to believe they exaggerated fiscal problems to justify tax rises, that brand is damaged.

Opposition parties have seized on the row, accusing Reeves of lying or at least “spinning” the numbers beyond recognition. Some have called for formal investigations into whether she breached the ministerial code by giving a misleading impression of the OBR’s advice. Others have suggested that her position as chancellor is now in question, especially if public trust continues to slip.

Starmer, however, has given Reeves full backing. He insists that neither voters nor Cabinet colleagues were misled and that he was kept informed of the evolving forecasts. He argues that the £16 billion hit from the productivity downgrade was real, even if higher revenues offset part of the blow, and that it would have been reckless to treat a narrow surplus as a comfortable starting point.

The tension here is as much about tone as substance. Governments often talk about “fiscal black holes” to frame difficult choices. In this case, though, the phrase has collided with detailed, published numbers that tell a more complicated story, making the language look, to many, like a political device rather than a neutral description.

The OBR leak, resignation, and independence

Running alongside the dispute over language is a separate institutional crisis. On Budget day, the OBR’s flagship Economic and Fiscal Outlook appeared online before Reeves had even begun her speech, allowing journalists and traders to access market-sensitive information early.

An investigation later concluded that the early publication was not an intentional leak but stemmed from configuration errors in the WordPress-based system used to host OBR reports. Because file URLs followed a predictable pattern and were uploaded to an area that was assumed to be secure, persistent attempts to guess the link eventually succeeded. The watchdog described the episode as the worst failure in its 15-year history, and its chair, Richard Hughes, resigned, taking responsibility.

Starmer called the incident a “serious error” and a “massive discourtesy” to Parliament, piling pressure on the OBR even as he reaffirmed support for its role in the fiscal framework. Critics worry that focusing too heavily on the leak risks turning the OBR into a scapegoat when the deeper problem lies in how its forecasts were spun in public. Others argue that clear accountability for such a serious operational failure is essential to maintaining credibility.

Either way, the timing is awkward. The institution meant to enforce transparency and discipline now finds itself apologizing for a basic lapse in information security, at the very moment when its independence and honesty are central to a fierce political dispute.

Media, messaging, and the BBC row

One of the most explosive elements of the saga is the claim by the BBC’s political editor that the broadcaster was misled by the Treasury’s pre-Budget messaging. He said viewers were primed to expect a large black hole and potential income tax rises because that is the picture the government painted off-camera.

This matters for two reasons. First, it highlights the power of background briefings in shaping public debate. Most voters never see the OBR’s tables, but they do hear headlines distilled by journalists who rely on what ministers and officials tell them. If those briefings omit key information — such as the fact that higher revenues had offset much of the productivity shock — the resulting story can be skewed even without any explicit falsehood.

Second, it raises questions about how broadcasters should handle official spin. The BBC has faced criticism in recent years from different political camps. Its willingness in this case to say publicly that it felt misled adds to the pressure on the government, and could mark a harder line in future when reporting on fiscal claims.

Why This Matters

The row over the Rachel Reeves budget black hole is not just a Westminster drama. It goes to the core of how modern democracies manage economic policy in an era of tight public finances and low trust.

In the short term, the Budget will shape taxes, benefits, and public services for millions of people. In the longer term, the way this dispute is resolved will influence whether voters believe future warnings from any chancellor — Labour or Conservative — when they talk about tough choices and limited room for maneuver.

The episode also feeds into wider global trends: rising skepticism toward expert institutions, from central banks to epidemiologists; high inflation and weak growth forcing governments into unpopular decisions; and intense scrutiny of whether political leaders are straight with the public about trade-offs.

Key moments to watch include any inquiry by Parliament’s Treasury Select Committee, further OBR reforms after the leak, and opinion polling on trust in both Reeves and Starmer. If the chancellor’s narrative fails to recover, the Budget could become a defining moment for the government’s wider economic project.

Real-World Impact

Consider a typical middle-income household. Its members already face frozen tax thresholds, higher indirect taxes, and elevated living costs. They might have accepted new tax rises if they believed the country genuinely faced a sudden hole in the public finances. Learning later that the official forecasts showed a small surplus instead of a yawning gap is likely to fuel cynicism and a sense of being played.

A small business owner, planning investment and hiring over the next few years, must now factor in not only higher employer taxes but also the risk that future fiscal statements will arrive wrapped in similarly dramatic language. That uncertainty can encourage caution, undermining the very growth the government says it wants to unleash.

In financial markets, investors scrutinize not just the numbers but the story around them. A perception that the UK over-dramatizes fiscal challenges or uses independent institutions as shields can erode confidence, raise borrowing costs at the margin, or push capital elsewhere. While there is no sign of an immediate crisis, reputational damage accumulates over time.

Within the public sector, departments and frontline services are trying to plan under tight spending settlements. Confusion over whether tax rises were truly unavoidable or driven by political priorities can complicate negotiations, morale, and the willingness of unions and local authorities to accept further restraint.

Conclusion

The battle over Rachel Reeves’s alleged budget black hole is a clash between narrative and numbers. On one side is a government that framed its tax-raising Budget as a response to an unforgiving inheritance and a tougher-than-expected outlook. On the other are critics who say the OBR’s own figures tell a subtler story — of shrinking headroom, yes, but not of the existential gap implied by talk of a looming hole.

Layered on top is the OBR’s own crisis: an accidental leak, a damning report, and the resignation of its chair. Together, these events have turned what might have been a standard post-Budget argument into a broader test of the UK’s fiscal architecture.

The key fork in the road is clear. Either the government convinces voters that its language was within the bounds of normal political framing, or the impression will harden that it overreached, damaging trust it can ill afford to lose.

What happens next will be signaled less by another flurry of statements than by quieter indicators: whether the OBR emerges from reform with stronger authority, whether Reeves can sell future Budgets without leaning on the language of crisis, and whether the public believes that when ministers talk about black holes, they are describing economic reality rather than political convenience.