What Would Alan Turing Think of the Modern Day?

Imagine the mind behind the first ideas of a universal computer — and the man who helped break the codes of the World War II — waking up in 2025. That man is Alan Turing. His life and work shaped the foundations of modern computing, artificial intelligence, cryptography and even mathematical biology. But he was also persecuted for his sexuality. So the question arises: how might Turing react to the world as it is now — a world transformed by computing, global connectivity, shifting social norms, and fierce debates over privacy, identity, and technology?

This article explores Turing’s worldview, his values and achievements. It draws parallels between his time and ours. And it imagines, cautiously, where he might find hope — or horror — in today’s digital, socially complex world.

We unpack what we know of Turing: his intellectual legacy, his moral struggles, and the social context he lived in. Then we consider how those elements might resonate — or clash — with the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

Key Points

Alan Turing pioneered the concept of a universal computing machine — the “Turing machine” — which laid the theoretical foundation for all modern computers and algorithms.

During WWII, Turing’s cryptanalysis work at Bletchley Park cracked the German Enigma codes, contributing significantly to the Allied victory.

After the war, Turing helped design early stored-program computers and pioneered ideas about machine intelligence and mathematical biology — areas only lightly explored in his lifetime.

Turing faced tragic persecution: in 1952 he was convicted under anti-homosexuality laws, forced into chemical castration, and stripped of his security clearance. He died in 1954.

Since then, acknowledgements and redress have come: he was posthumously pardoned and celebrated, inspiring legal reforms, social progress, and symbols like his image on the UK £50 note.

In many ways, modern computing, AI, LGBTQ+ rights, and digital privacy debates are deeply connected to the frameworks Turing helped establish — making him as relevant now as he was in his time.

Background

Alan Turing was born in London in 1912. He studied mathematics at Cambridge and then went to Princeton for his PhD in logic. In 1936, he published a seminal paper defining what later became known as the “Turing machine.” That theoretical device set out what it means for a problem to be “computable” — in other words, which problems could be solved by an algorithm. This laid the foundations for modern computer science.

When war broke out, Turing brought his talents to the encrypted war-time communications of Nazi Germany. Working at the secret facility known as Bletchley Park, he led the efforts to crack German naval codes — especially those sent via the Enigma machine. The decrypted intelligence, known as Ultra, was instrumental in Allied operations and is widely believed to have helped shorten the war.

After WWII, Turing helped design some of the first stored-program computers at the National Physical Laboratory and later the University of Manchester. He also began exploring whether machines could “think” — introducing what became known as the “Turing Test” — and speculated on biological patterns, foreshadowing mathematical biology.

Yet his life ended in tragedy. In 1952, he was convicted under British laws that criminalised homosexual acts. To avoid prison, he accepted chemical castration. His security clearance was revoked, cutting short sensitive work. Two years later, he died — officially ruled a suicide by cyanide poisoning, though some argue it may have been accidental.

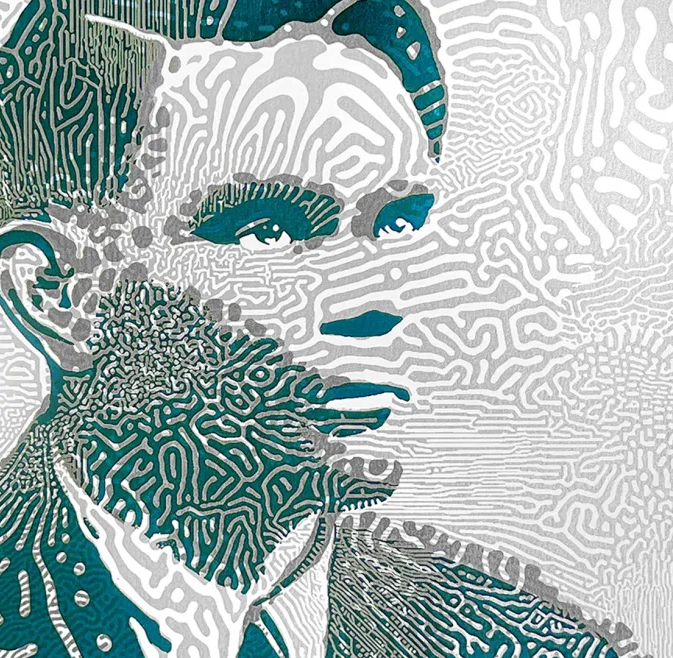

In subsequent decades, public reckoning led to a posthumous pardon, symbolic redress for thousands of others via the informal “Turing’s Law,” and growing recognition of his intellectual and moral legacy. In 2021, the highest-value Bank of England note — the £50 note — began featuring his portrait and references to his scientific work.

Analysis

Core Beliefs and Priorities

Turing saw computation as a universal concept. To him, a machine was not a mere calculator, but a formal embodiment of logical processes. The “Turing machine” concept was abstract, divorced from physical hardware. That universality — that algorithms and logic transcend hardware — is now the bedrock of computing, software development and even modern AI.

He believed machines might one day challenge our assumptions about intelligence. In a 1950 paper, he asked: “Can machines think?” and proposed an “imitation game” — what became the Turing Test — as a practical way to explore that question.

Beyond pure logic, Turing was keenly aware of the real-world implications of cryptography. In wartime, codebreaking was not abstract mathematics: it was about survival, lives, and the future of nations. His work demonstrated that abstract mathematical insight could change the course of history.

At the same time, Turing experienced the weight of prejudice. His treatment under the law for being homosexual — despite his enormous contributions — reveals that his values included intellectual honesty, human dignity, and perhaps the painful knowledge that brilliance and social acceptance do not always align.

Parallels with Today’s Debates

Modern computing — ubiquitous smartphones, global internet, social media, cloud computing, encryption — is fundamentally shaped by the frameworks Turing laid down. Whether it is a smartphone, a quantum computer in development, or a machine-learning model running on a server: it all descends from the idea of a universal machine that manipulates symbols.

The debate over machine intelligence — whether computers can think, reason, or “understand” — continues full force today with advances in large-scale machine learning, neural networks, and chatbots. The questions Turing posed remain alive and urgent.

Cryptography and digital security — now essential to everyday online banking, communication, voting systems and national security — trace a direct line to Turing’s wartime cryptanalysis. The tools and ethical dilemmas around privacy, surveillance, encryption and state power remain deeply relevant.

Social justice and equality: Turing’s personal story highlights the arbitrary and cruel nature of laws that criminalised people for their identity. The partial redress granted decades later resonates with ongoing fights for LGBTQ+ rights globally — and the need to recognise that societies lose out when they suppress talent.

Where the Past Clashes With the Present

The pace and scale of modern computing may well surprise Turing. The sheer volume of data, constant connectivity, global platforms, and commercialisation of digital life might feel like a distortion of the elegant, idealised machines he imagined in the 1930s.

He might be uneasy about how algorithms are used — for surveillance, targeted advertising, political manipulation — especially if applied without transparency, oversight or accountability. The universal machine, in theory neutral, can become a tool for both empowerment and control.

Given his experiences of discrimination, Turing may view with cautious optimism the advances in social acceptance and legal protections — yet he might also recognise how much remains fragile, contested, and subject to backlash.

Finally, the question he posed — “can machines think?” — remains unsettled. Advances have blurred lines between human and machine abilities, yet fundamental dilemmas about consciousness, morality, responsibility, and meaning remain.

Why This Matters

Looking at the modern world through Turing’s lens helps clarify core tensions in contemporary debates about technology, identity, and justice. His life combines brilliance and vulnerability — demonstrating how a single individual’s ideas can reshape the world, while social prejudice can devastate lives.

Today’s conversations around AI ethics, data privacy, encryption, algorithmic bias, and digital identity draw on exactly the foundations Turing helped build. Recognising that lineage helps ground these debates in deeper historical perspective.

The struggle for equal rights for LGBTQ+ people remains relevant. Turing’s posthumous pardon and symbolic rehabilitation remind us that lawsshape not just behaviour — but who society values, respects, and cultivates.

And as computing becomes ever more central to life — from banking to governance, from health to entertainment — the questions Turing asked remain vital. Are machines mere tools? Or could they challenge our conception of humanity?

Real-World Impact

A young computer scientist in 2025 writing code for smartphones, cloud services or AI models stands on top of the theoretical structure Turing built with his conceptual “universal machine”. Without that foundation, modern software would be impossible.

Cryptographers, cybersecurity experts and national security agencies still rely on principles Turing helped formalise — his wartime work echoes in today’s encrypted messaging apps, secure online voting, and crypto-resilience efforts.

The legal reforms that pardoned people convicted under old anti-homosexuality laws (known informally as the Alan Turing Law) continue to shape debates about historical injustice, stateless offences, and societal recognition of LGBTQ+ lives.

Cultural memory: Turing’s image on the UK £50 note, public statues, museum exhibits and education programmes help remind younger generations about the interplay between genius, trauma and social justice — and the human cost of prejudice.

Conclusion

If Alan Turing were alive today, he might be astonished. The machines he envisaged — pure logic, universal computation — have grown into a global infrastructure. The world hums to their circuits. Cryptography protects our secrets; networks connect billions; artificial intelligence probes old questions about mind and meaning.

Yet he might also be troubled. The scale, pace and commercial pressures may distort the original ideal. The use of computing for surveillance, manipulation and inequality might strike him as a betrayal of the universal promise. And, despite progress, he might quietly mourn that so many brilliant minds — like his own once nearly were — could still be lost to prejudice and fear.

At the same time, he might find hope in modern efforts for inclusion, equality, transparency, and ethical responsibility. The fact society now honours him — a gay man, once persecuted — suggests that moral progress, though slow, is possible.

Turing’s legacy is not only in machines and algorithms. It lies also in the reminder that great ideas flourish best when we guard justice, dignity and human potential.

These reflections are interpretive and speculative, offering a modern lens on historical ideas rather than asserting definitive claims