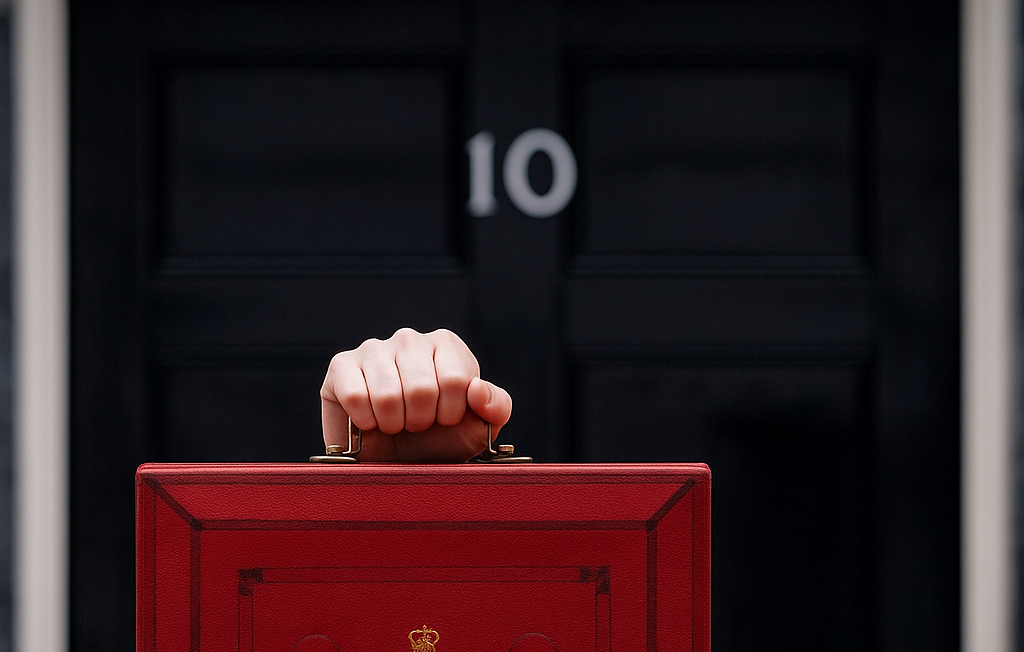

Rachel Reeves Accused of Misleading Britain Over Budget ‘Black Hole’

Britain’s first woman chancellor is facing one of the toughest weeks of her tenure. Rachel Reeves is accused of painting an unduly bleak picture of the public finances in the run-up to the 2025 Autumn Budget, even after she had been told that a predicted “black hole” had disappeared.

At the center of the row is a simple but explosive question: did the chancellor mislead the public about the state of the nation’s finances to prepare the ground for record tax rises, or was she legitimately stressing fiscal risks to defend cautious budgeting?

New letters from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the UK’s fiscal watchdog, show that by late October the Treasury had been informed that stronger-than-expected tax receipts had more than offset earlier worries about weak productivity. Yet days later, Reeves delivered a high-profile speech warning of tough choices, a £20 billion fiscal gap, and the need for painful tax decisions.

This article unpacks how the controversy arose, what the OBR actually told ministers, why opposition parties and economists say the chancellor crossed a line, and how Downing Street and sympathetic analysts are defending her. It also looks at what this clash means for trust in Britain’s new government, the independence of the OBR, and the direction of fiscal policy in a country already facing its highest tax burden in modern times.

Key Points

Rachel Reeves is accused of overstating a £20 billion “black hole” in the public finances before the 2025 Budget, despite being told weeks earlier that the gap had closed.

OBR correspondence shows the watchdog informed the Treasury in September that the downgrade to productivity would be small, and by 31 October projected a £4.2 billion surplus rather than a deficit.

Reeves went on to introduce around £26 billion of tax rises, taking the UK tax burden toward record levels and provoking fierce criticism from business and opposition parties.

Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch and other critics say the chancellor “lied” to justify tax hikes, while Downing Street insists she simply set out the tough choices needed under the government’s fiscal rules.

Economists are divided: some argue the November speech was “misleading,” while others say Reeves may have been trying to signal seriousness to markets and build a buffer against future shocks.

The row comes on top of a separate controversy after the OBR accidentally published its Budget assessment early, now being examined by financial regulators.

Background

A chancellor under pressure

Rachel Reeves entered the Treasury promising “iron discipline” after years of economic turbulence, weak growth, and public anger over stretched services. Her early months were dominated by a spending audit that she said uncovered a £21.9 billion gap in the plans she inherited, a narrative that framed Labour as cleaning up after Conservative mismanagement.

By the time of the 2025 Autumn Budget, expectations were set for more tax rises. The UK was already on course for the highest overall tax burden since the Second World War, after Reeves’s earlier 2024 budget raised around £40 billion through measures such as higher employers’ National Insurance contributions and changes to farm inheritance tax.

Into this fraught context came fresh economic headwinds. Forecasts suggested weaker productivity growth, partly linked in Reeves’s rhetoric to global trade tensions and Donald Trump’s renewed tariff policies. The fear was that slower productivity would drag down long-term output and squeeze the “headroom” available under the government’s self-imposed fiscal rules, which require debt to be falling as a share of GDP in the medium term.

The role of the OBR

The Office for Budget Responsibility is tasked with producing independent forecasts and judging whether the government’s tax and spending plans meet its fiscal rules. While ministers decide policy, the OBR’s numbers anchor the debate.

Ahead of each budget it runs a set of “pre-measures” forecasts, based on current policy, and then updates them once the Treasury has decided on tax and spending changes. The gap between these two sets of numbers helps determine how much room a chancellor has to spend or cut taxes while still satisfying their rules.

In this case, the OBR told Reeves in mid-September that the impact of weaker productivity on the public finances would be much smaller than feared—around £2.5 billion—because high inflation and wage growth were boosting tax receipts. By 31 October, it estimated that instead of a deficit there would be a £4.2 billion surplus before any new policy measures.

Despite this, public messaging from the Treasury continued to stress a looming shortfall, culminating in Reeves’s 4 November speech setting out the case for tax rises and warning of “hard choices” forced by the OBR’s downgrade.

Analysis

Political stakes and narrative warfare

The accusations facing Rachel Reeves strike at more than just the details of a single forecast. They cut to the heart of how Britain’s new government presents its economic story and how far voters can trust its claims.

Opponents argue the chancellor framed the OBR’s work in a way that suited her political aims. By talking up the idea of a £20 billion or £22 billion “black hole,” critics say, she softened up the public and her own party for large tax rises that were always central to Labour’s plans to expand the welfare state and invest in public services.

Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch has accused Reeves of “lying to the public to justify record tax hikes” and called for her to be sacked. Others on the right are using the row to revive long-standing claims that Labour cannot be trusted with the economy.

Labour figures push back hard. They argue that Reeves levelled with voters about tough realities—weak growth, an ageing population, creaking infrastructure—and chose to protect spending on health, education, and climate investment rather than pursue deep cuts. From this perspective, highlighting fiscal risks was part of a broader effort to show markets and the public that Labour is serious about keeping debt on a stable path, even if that means unpopular tax decisions.

The clash is sharpened by memories of recent crises, especially the 2022 mini-budget that spooked bond markets and sent mortgage costs soaring. Any hint that a chancellor might be playing fast and loose with fiscal numbers instantly invites comparison, even when the substance is very different.

Economic and market impact

The budget itself raises around £26 billion through 43 separate tax measures, including extending income tax threshold freezes, tightening pension reliefs, and new levies on property and wealth. The OBR projects that by the end of the decade one in four workers will pay the higher income tax rate, and the overall tax burden will reach roughly 38 percent of GDP.

From a narrow fiscal standpoint, Reeves can argue that the numbers still add up. The Budget meets the government’s fiscal rules with a buffer, albeit one some economists say is too thin. Building a larger cushion now, they argue, reduces the risk of having to make further emergency decisions if growth disappoints again.

But the way the chancellor framed the pre-Budget situation matters for markets as well as politics. If investors suspect that ministers are shading the truth for tactical advantage, trust can erode. That is especially sensitive when Britain depends heavily on international capital to finance its debt.

So far, market reaction has been relatively calm. Bond yields ticked up but not dramatically, and there were no signs of the outright panic seen in 2022. However, the early, accidental publication of the OBR’s report—now under investigation by the Financial Conduct Authority—has added to a sense of procedural chaos around what is supposed to be a tightly controlled fiscal event.

Accountability and the OBR

The OBR’s role in this story is delicate. On one hand, its letters to Parliament have exposed the timeline of information given to the Treasury and forced a correction of the public record. On the other, some in government are frustrated that internal discussions about forecasts have spilled out in such detail.

The watchdog is adamant that it did not revise its pre-measures forecast after 31 October, undermining briefings that Reeves only learned of improved numbers in mid-November.

Supporters of the OBR see this as an example of why independent institutions matter. When political incentives tempt ministers to emphasize worst-case scenarios, an arm’s-length body with a legal mandate to publish its assessment can push back.

Critics, however, worry that the OBR itself has become a political actor, whether it wants to be or not. The leak of its Budget assessment hours before Reeves stood up in the Commons has triggered calls for tighter protocols, and some MPs question whether the watchdog should be more cautious about how it communicates with Parliament in the heat of a political row.

Public trust and political communication

Beyond the technicalities, the dispute raises a bigger issue: what counts as “misleading” in politics?

Economists such as Paul Johnson, the former long-time director of a leading fiscal think tank, say the November press conference “probably was misleading,” arguing that the chancellor spoke as if she faced a huge gap that had to be filled by tax rises when she already knew the numbers looked better.

Others note that fiscal forecasts are uncertain by design. Governments often choose to emphasize downside risks to justify building buffers, especially after years in which optimistic assumptions left them scrambling when growth slipped. From this angle, Reeves’s stark language could be read less as a literal description of the figures on her desk and more as an attempt to set expectations for a cautious Budget.

For voters, the distinction may feel academic. People see a government that promised stability and honesty now arguing over whether its own warnings were exaggerated. At a time when trust in institutions is already fragile, that is a political cost in itself.

Why This Matters

The row over whether Rachel Reeves misled Britain may sound technical, but it has wide implications.

For households, the Budget means higher taxes over the coming years and only modest relief on living standards after a long squeeze. Whether those sacrifices feel justified depends partly on whether people believe ministers are levelling with them about why the money is needed.

For businesses and investors, credibility is currency. A chancellor seen as frank and predictable can generally borrow at lower cost than one suspected of spin. The argument about the “black hole” adds another layer of uncertainty about how future fiscal announcements should be read.

For the government, this is also a test of its broader promise to restore trust after years of scandal and instability. If the narrative hardens that it exaggerated fiscal problems to disguise an ideological choice for a bigger state, that could shape politics well beyond this Budget cycle.

Finally, the case will feed into a larger international debate about independent fiscal institutions. As more countries rely on watchdogs like the OBR, the boundaries between neutral forecasting and political storytelling are under scrutiny.

Real-World Impact

Consider a typical mid-income professional who has not seen a big pay rise in real terms for years. Because income tax thresholds remain frozen while wages inch up, more of their salary is dragged into higher tax bands, leaving little extra in their pay packet even when the economy grows. The justification for this “fiscal drag” matters when they decide whether the system feels fair.

A small manufacturing firm faces higher costs from increased employer National Insurance contributions and tighter reliefs on investment. Its owners weigh whether to hire extra staff or automate instead. If they believe taxes rose because the government was boxed in by unavoidable fiscal holes, they may tolerate the pain; if they conclude the narrative was exaggerated, resentment builds.

In the public sector, a regional hospital sees some additional funding but must still navigate tight budgets and staff shortages. Managers follow Budget debates closely: if they sense that spending limits were justified on the basis of an overstated crisis, morale can suffer, and unions may be more likely to push for confrontations.

Even financial markets are not immune to psychology. Bond traders and analysts may accept that the fundamentals of the UK economy have not changed, yet the perception that fiscal stories are massaged can make them more cautious, demanding a little more yield to hold British debt. Over time, that marginal shift can add billions to the government’s interest bill.

Conclusion

The accusation that Rachel Reeves misled Britain before her Budget is unlikely to fade quickly. It touches on money, trust, and the fragile relationship between elected politicians and the institutions meant to police their sums.

At one level, the numbers are clear: forecasts that once pointed to a sizeable fiscal gap were later revised to show a surplus, yet the political narrative of looming crisis rolled on. At another level, the story is murkier: governments routinely lean into caution, and the line between prudent messaging and distortion is hard to draw.

What happens next will depend on several factors: whether parliamentary committees choose to dig deeper into the OBR’s timeline, what conclusions regulators reach about the leak of Budget documents, how markets respond if growth again undershoots, and whether voters feel the promised benefits of Reeves’s high-tax strategy in their everyday lives.

For now, the episode is a reminder that in modern politics, the battle is not only over what the numbers say, but over who gets to tell the story first—and how honestly they choose to tell it.