What Sparked the Industrial Revolution?

Britain’s Cheap Coal, Costly Labor, and the Factory Breakthrough

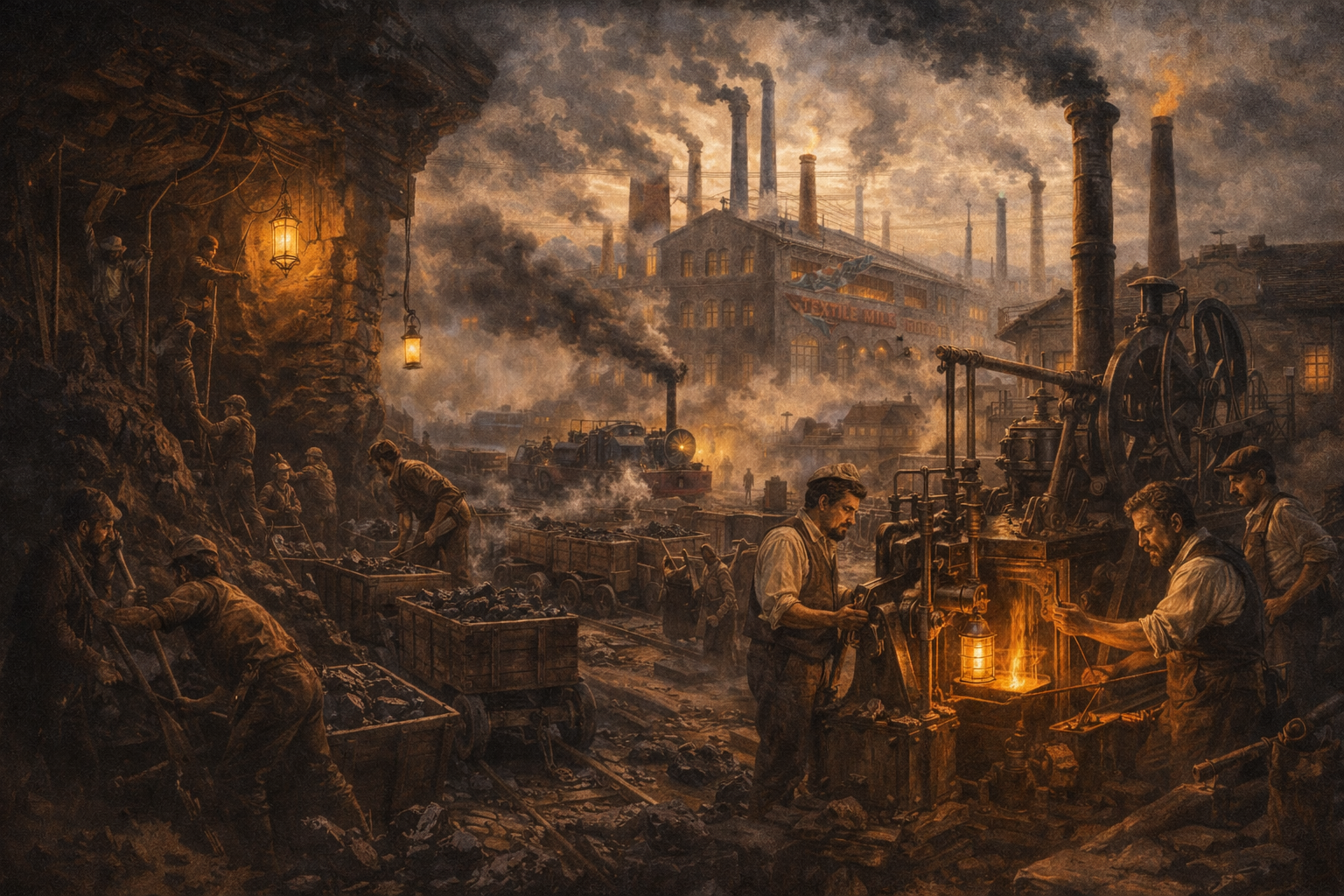

The Industrial Revolution. It was not a single invention, and it did not begin everywhere at once.

In the most decisive window—Britain from roughly 1700 to 1830—the problem was simple to state and challenging to solve: how to produce far more goods with limits on skilled hands, animal power, and the speed of transport.

What made it matter was power. The country that learnt to convert fossil energy into cheap, repeatable work could outproduce its rivals, equip and supply larger states, and sell to distant markets at prices that handwork could not compete with.

Britain’s early lead came from a particular stack of conditions: abundant coal close to industry, incentives that made labor-saving machinery pay, and institutions and skills that let inventors and investors keep pushing imperfect machines until they worked at scale.

Historians still argue about which factor mattered most—wages, coal, ideas, empire, or state capacity—but the clearest mechanism is that Britain was the place where new machines were both technically buildable and economically worth building.

The story turns on how cheap energy, costly labor, and scalable institutions turned clever devices into a new system of production.

Key Points

The Industrial Revolution was the shift from agrarian and handicraft production to machine manufacturing, factories, and new energy use, first taking off in 18th-century Britain.

Its early origin point was Britain in the mid-1700s, where coal-powered industries and mechanized textiles began to outperform home and workshop production.

A major turning point was mechanized cotton spinning and the factory system in the 1760s–1770s, which concentrated workers and machines under one roof.

Another important change was that better steam power became useful in more places than just mines, which made industrial power less dependent on rivers.

The biggest constraint was moving bulky fuel and materials in a world before rail: getting coal, iron, and goods to the right place at the right time, which shaped where industry could grow.

The most significant change was in the economics of time and output: machines and energy increased the productivity of each worker; however, inequality, strict discipline, and uneven gains persisted.

The clearest legacy is the carbon-energy, high-output economy—steam, coal, and mechanized production as a template later copied worldwide.

Context

Before the “revolution,” Britain was not a blank slate. It already had busy ports, growing towns, active domestic trade, and a long tradition of small-scale manufacturing—especially textiles made in homes and small workshops.

Energy and materials were the primary constraints. Waterwheels and muscle could power only so much, and only where geography allowed. Coal existed in enormous quantities, but mining deeper meant water, and water meant pumps.

Demand was also shifting. Consumers wanted more cloth, more metal goods, more household items. Merchants wanted dependable supply. The state wanted ships, cannon, and revenue. Those pressures rewarded output that was steady, predictable, and scalable.

By the early to mid-1700s, Britain was primed because constraints were tightening at the same time opportunities were widening: towns grew, fuel demand rose, and the payoffs for replacing skilled time with machine time started to look real.

The Origin

A good place to pin the origin is the mid-18th century turn toward mechanized textiles and coal-based power, when inventors and entrepreneurs began building systems, not just gadgets.

In cotton, the aim was not to “change history.” It was to spin more yarn, more consistently, at lower cost, to meet demand and beat rivals. In mining, the aim was to drain deeper pits and pull more coal, because coal made heat, motion, and profit.

What many actors could not yet see was that combining machinery, disciplined work routines, and reliable power would reorganize daily life: where people lived, how time was measured, how skills were valued, and how fast a region could grow or collapse.

The conditions that made the origin possible were concrete: accessible coal, workable water power, improving transport, enough capital to build fixed works, and a skills system that produced competent builders and fixers—not only idea people.

The Timeline

1700–1760: The energy problem became solvable due to coal, pumps, and other innovations.

On the ground, Britain’s economy was still dominated by agriculture and small manufacture, but mining and metallurgy mattered more each decade because they fed everything else.

The mechanism was pragmatic engineering aimed at bottlenecks. Mines flooded; pumps improved. Deeper mining made more coal available, and coal lowered the effective cost of energy, especially near coalfields.

The constraint was location. Power came from rivers, wind, animals, and crude early steam, and it was expensive to move heavy loads on unsafe roads.

The carry-over was decisive: once coal could be mined in larger volumes and used more widely, energy stopped being only a local gift of geography and started becoming something that could be extracted and expanded.

1760–1785: Cotton mechanizes and the factory becomes the winning container

On the ground, textile production began shifting from dispersed household work to concentrated sites with machines and strict routines. Cotton stood out due to its high demand and the ability to break down the technical tasks of spinning and weaving into repeatable steps.

The mechanism was a chain of labor-saving devices and, crucially, the decision to gather them in one place. Once large-scale spinning could happen on a single machine, it made sense to centralize oversight, maintenance, and pace.

The constraint was power reliability. Early mills leaned heavily on water, so growth clustered around suitable streams and valleys. Even where the market existed, geography still rationed expansion.

The carry-over was a new template: production as a managed flow, with workers, machines, and time disciplined under one roof. That template was portable—if power could be made portable.

1785–1815: Steam power breaks the river lock, and transport starts catching up

On the ground, industrial sites multiplied and diversified. Steam engines were no longer only about draining mines; they began driving machinery, raising output, and smoothing seasonal limits.

The mechanism consisted of improved steam technology and the expansion of a coal supply system, which made constant power feasible. The more steam spread, the more it pulled demand for coal, iron, and skilled machine work behind it.

The constraint was a moving bulk. Coal, ore, and finished goods were heavy, and weather and poor roads made delivery uncertain. That uncertainty pushed investment into canals and better roads to cut costs and stabilize supply.

The carry-over was a tighter national market. When a canal could slash the price of coal in a growing town, it changed where factories could profitably run and how quickly industrial districts could expand.

1815–1830: Iron, machines, and the beginnings of the railway age

On the ground, ironmaking and machine-building deepened the revolution. Better metals and more precise parts made engines and factory machinery more reliable, and reliability lowered the risk of investing in yet more fixed capital.

The mechanism was cumulative. Each improvement in tools, iron, and engines made the next improvement easier to build and cheaper to maintain. The industrial economy began to generate its own problem-solvers.

The constraint remained coordination: fuel supply, skilled labor, and capital still had to meet in the same places, and breakdowns could idle entire works.

The carry-over was momentum. Once industrial capacity became a system—power, metal, tools, transport, finance—growth became easier to reproduce and harder to stop.

1830 and after: Scale, spread, and social strain become impossible to ignore

On the ground, industrial production expanded faster than housing, sanitation, and labor protection. Cities grew, and factory discipline hardened.

The mechanism was diffusion. Techniques that were first profitable in Britain became exportable as engineering improved efficiency and as other countries built coal supply and transport.

The constraint was human and political: long hours, injuries, child labor, and urban disease created pressures that eventually demanded regulation and reform.

The carry-over was global: once machine production and fossil energy became normal, other states had to adapt or be outcompeted.

The single hinge marked the transition from industrial power's reliance on specific rivers to its ability to follow fuel, capital, and markets.

Improved steam engines mattered because they turned coal into controllable motion on demand. That meant a factory could run longer, steadier hours and could be placed for logistics and labor, not only for water flow.

The realistic alternatives at the time were not “no steam” versus “steam everywhere.” They were incremental: more water mills, more localized growth, and slower scaling where geography allowed. Steam did not invent the factory, but it made the factory model far easier to multiply.

Consequences

In the short run, output rose and unit costs fell in key goods, especially textiles and iron-related products. That widened markets and increased the rewards for further mechanization.

The second-order effects were bigger than any single industry. New kinds of firms and finance became normal for large fixed investments. Skills shifted: fewer tasks depended on long craft training, while more depended on machine tending, repair, and supervision. Work time became stricter, measured by clocks and output targets rather than seasons and daylight.

State capacity also changed. Industrial production strengthened revenue bases, supported naval and military supply, and increased the strategic value of coal, iron, and transport corridors.

The social costs were severe. Factory work could be dangerous, hours long, and wages often low. Urban crowding and pollution reshaped health and family life. Even where living standards improved over the long run, the path was uneven and contested.

What Endured

Land, class, and hierarchy did not vanish. Old elites adapted, invested, and kept political influence even as new industrial fortunes rose.

Geography still mattered. Coalfields, ports, and navigable routes continued to steer where industry clustered, even after steam reduced dependence on rivers.

Global trade remained a backbone. Britain’s industrial growth fed on imported raw materials and sold into overseas markets, entangling industry with imperial power and coercive systems of labor beyond Britain itself.

Limits on welfare and rights persisted. Early industrial society tolerated long hours, child labor, and harsh discipline far longer than later generations would accept.

Disputed and Uncertain Points

How “high wages” really were, and for whom, remains debated. One influential view stresses that Britain’s wage-and-energy price structure made labor-saving machinery unusually profitable; others argue wages varied by region and sector and do not explain everything on their own.

The role of empire and slavery is also contested. Many historians agree Atlantic trade and slave economies shaped markets and capital flows, but they disagree on whether slavery was a primary driver of industrial takeoff or a powerful accelerator among several causes.

Even the “revolution” label is argued over. Some scholars emphasize a sharp break in growth and capability around the late 18th and early 19th centuries; others stress longer continuities and gradual diffusion across decades.

Legacy

The Industrial Revolution’s most visible legacy is the energy bargain it normalized: burn fossil fuel to multiply human work.

That bargain built the modern factory, the modern growth economy, and the modern expectation that each generation can be materially better off than the last. It also set the template for carbon dependence, urban-industrial inequality, and the global race to control energy, supply chains, and productive capacity.