Astronomers Detect 8-Billion-Year-Old Fast Radio Burst Older Than the Solar System

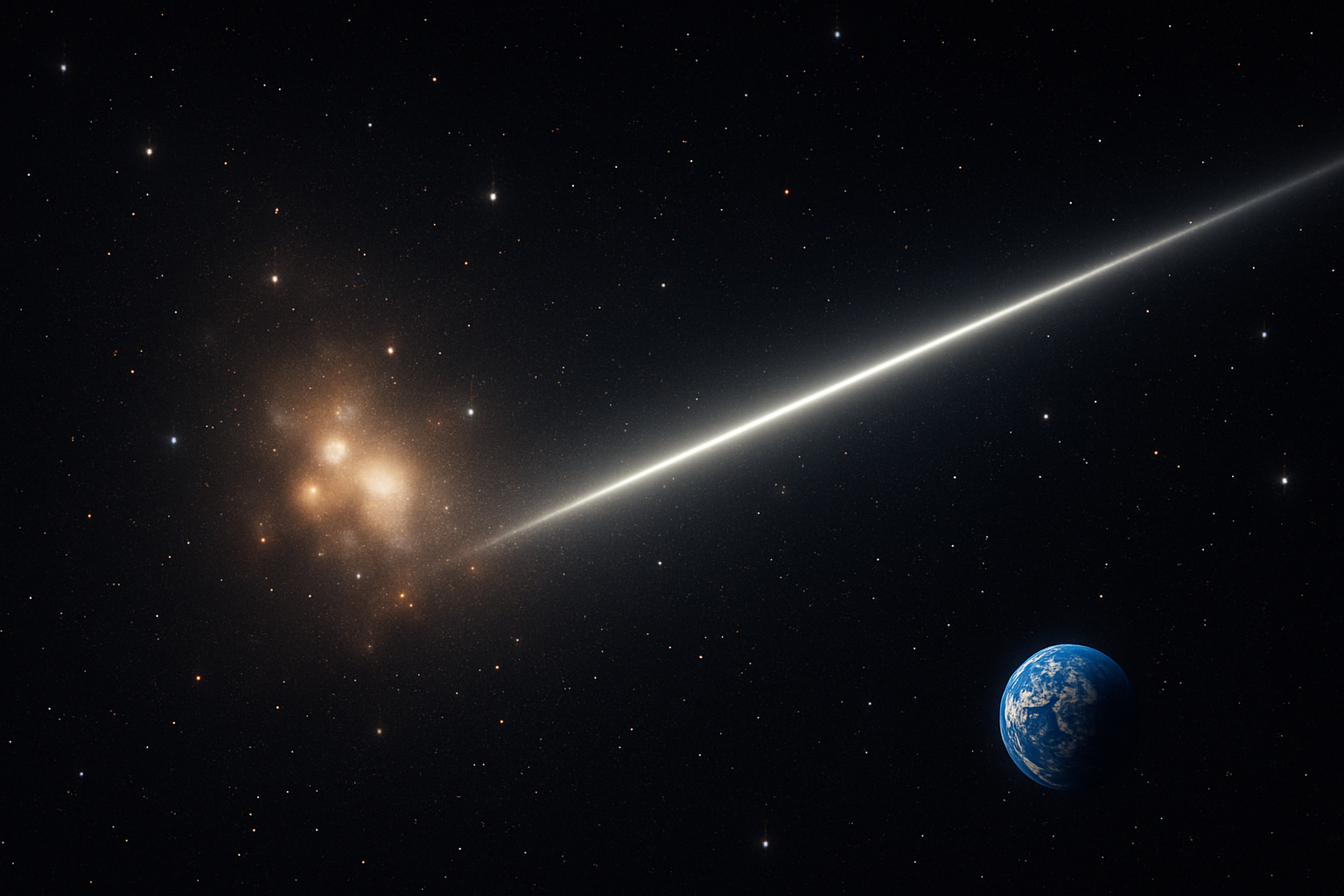

A flash of radio light no longer than the blink of an eye has just rewritten the record books. The signal, a fast radio burst known as FRB 20220610A, left its home galaxy around 8 billion years ago—more than 3 billion years before the Sun and Earth even existed.eso.org+1

In that split second, it released as much energy as the Sun emits in roughly 30 years, then crossed half the observable universe before finally brushing past a radio telescope in the Australian outback.skao.int+1

The discovery is more than a curiosity about a distant, violent event. It pushes fast radio bursts (FRBs) to their known distance limit, challenges ideas about how powerful these explosions can be, and turns them into precision tools for weighing the “missing” normal matter in the cosmos.skao.int+1

This article explains what FRB 20220610A is, how astronomers tracked it back to a tangle of merging galaxies, and why this single flash is now central to efforts to map the hidden matter between galaxies. It also sets the burst in the wider story of FRBs, from nearby eruptions tracked by radio arrays and the James Webb Space Telescope to the latest hints about their mysterious engines.NASA Science+2Live Science+2

By the end, the picture that emerges is simple but striking: a universe where tiny, millisecond-long signals can light up its large-scale structure and expose matter that cannot be seen in any telescope image.

Key Points

Astronomers have detected FRB 20220610A, a fast radio burst whose light traveled for about 8 billion years, making it the most distant FRB located so far and older than the solar system.eso.org+1

The burst was first caught by the ASKAP radio telescope in Australia, then traced to a group of merging galaxies using major optical facilities, including the Very Large Telescope and other observatories.skao.int+2eso.org+2

In a few milliseconds, FRB 20220610A released energy comparable to 30 years of the Sun’s output, exceeding previous theoretical limits for FRB brightness and forcing a rethink of some models.skao.int+2Nature+2

The way the burst’s signal was stretched and delayed as it crossed space allowed astronomers to confirm a key relation between FRB distance and the amount of diffuse gas between galaxies, helping to “weigh” the universe’s missing normal matter.scienceinpublic.com.au+1

FRBs are increasingly being used as cosmic probes, even as their exact origins remain uncertain; leading candidates include magnetars, neutron star mergers, and other extreme compact objects.Wikipedia

New instruments and surveys are rapidly expanding the FRB catalogue, with other record-setting bursts—both extremely bright and unusually nearby—now being pinpointed to their home galaxies.MIT News+2Live Science+2

Background

Fast radio bursts were discovered in 2007, when astronomers noticed an odd, millisecond-long spike in old pulsar data. Since then, hundreds have been detected across the sky. Each one is a brief, intense pulse of radio waves that, at its source, can emit as much energy in a thousandth of a second as the Sun produces over several days or more.Wikipedia+1

Most FRBs come from far beyond the Milky Way. Some repeat at irregular intervals, while others have been seen only once. A handful show periodic activity cycles. Together, they have become one of the most puzzling phenomena in modern astrophysics.Wikipedia

A major breakthrough came in 2020, when a magnetar—an ultra-magnetized neutron star in our own galaxy—produced a radio outburst that looked like a weak FRB. That result confirmed that at least some FRBs can be powered by magnetars, though it did not rule out other engines.Wikipedia

At the same time, radio arrays such as ASKAP in Australia and CHIME in Canada have grown adept at catching FRBs in real time and localizing them to specific galaxies. Using multiple observatories at different wavelengths, astronomers have traced some bursts to star-forming dwarf galaxies, others to relatively quiet, older galaxies, and now to complex systems of galaxies in the process of merging.NASA Science+1

Within this broader story, FRB 20220610A stands out. It is not just another data point. It represents the far edge of what today’s instruments can see, and it arrives from an era when the universe was only about 5 billion years old—roughly one-third of its current age.eso.org+1

Analysis

Scientific and Technical Foundations

FRB 20220610A was detected on 10 June 2022 by the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder, a network of 36 radio dishes in Western Australia. ASKAP is designed to scan large regions of sky and, crucially, to pinpoint where a burst came from to within a small patch of sky.skao.int+1

When the burst hit ASKAP’s antennas, its signal was already stretched out in time. High-frequency radio waves arrived slightly earlier than low-frequency ones. This pattern is called dispersion, and it happens because the burst had to travel through clouds of ionized gas—electrons scattered between galaxies—that slow lower-frequency waves more.Universe Today+1

By measuring how dispersed the signal was, astronomers could estimate how much diffuse gas it had passed through. Combining that with the position from ASKAP, they turned to powerful optical telescopes such as ESO’s Very Large Telescope and Keck to identify a host system: a tight group of merging galaxies about 8 billion light-years away.skao.int+2eso.org+2

Knowing the distance means the burst’s energy can be calculated. Even for an FRB, FRB 20220610A is extreme. Its energy output in a few milliseconds rivals three decades of solar emission and appears to exceed the upper energy limit predicted by some models of FRB engines.skao.int+2Nature+2

This distant burst now sits alongside other record-setters. Recent work, for example, has identified the brightest FRB ever detected in the nearby universe, traced to a galaxy only about 130 million light-years away and imaged in detail by the James Webb Space Telescope. Together, these extremes—very near and very far—are starting to map out the full range of FRB behavior.MIT News+2Live Science+2

Data, Evidence, and Uncertainty

The evidence that FRB 20220610A is both ancient and distant rests on several layers of data:

ASKAP’s array geometry allowed precise triangulation of the burst’s sky position.skao.int+1

Optical and infrared imaging then tied that position to a compact group of interacting galaxies, with a measured redshift corresponding to about 8 billion light-years.eso.org+2NASA Science+2

The dispersion measure—the degree to which the signal’s different frequencies were delayed—matches what would be expected for a source at that distance passing through the intergalactic medium as described by cosmological models.scienceinpublic.com.au+1

There are, however, important uncertainties. The exact nature of the host system is still being refined. Hubble imaging suggests a complicated environment: a compact grouping of galaxies with active star formation and disturbed structures, rather than a single tidy spiral.NASA Science

The underlying engine of the burst is also not nailed down. Models must now account for both the intense energy output and the environment of merging galaxies. Magnetars formed in recent starbursts remain strong candidates, but other possibilities include interactions in dense stellar clusters, neutron star mergers, or accretion onto compact objects in binary systems. The data rule out some extreme scenarios but do not yet distinguish between the leading astrophysical options.Wikipedia+1

What is relatively secure is the energy scale, the distance, and the fact that this burst aligns with a key empirical relation—known as the Macquart relation—linking FRB dispersion to distance. That makes FRB 20220610A a valuable calibrator, even as its detailed engine remains uncertain.scienceinpublic.com.au+1

Industry and Economic Impact

This discovery sits in basic astrophysics, far from commercial product launches or consumer devices. Still, it has indirect implications for technology and industry.

Catching millisecond radio flashes across half the sky requires sensitive receivers, wide-field antennas, fast digital backends, and sophisticated real-time data pipelines. Facilities such as ASKAP and future instruments like the Square Kilometre Array drive advances in low-noise electronics, high-throughput computing, and signal-processing algorithms. Those same tools feed into telecommunications, radar, and remote sensing.skao.int+2skao.int+2

Large FRB surveys also demand new approaches to data management: archiving petabyte-scale time-series data, running rapid detection algorithms, and coordinating global follow-up across multiple observatories. Techniques pioneered here—automated event triggers, cross-facility coordination, and standardized data formats—spill over into Earth observation, satellite monitoring, and other data-intensive sectors.skao.int+1

From a funding standpoint, record-setting FRBs provide a compelling story for investment in next-generation radio arrays. They showcase how relatively modest ground-based facilities can deliver headline-grabbing science, strengthening the case for long-term public and international support.skao.int+1

Ethical, Social, and Regulatory Questions

FRB science raises few direct ethical dilemmas compared with fields like genetics or surveillance. The main social questions are about priorities and access. These include how much public funding should support large observatories, which countries host them, and how data and telescope time are shared.

There is also an ongoing need to manage radio spectrum. FRB searches are sensitive to interference from satellites, aircraft, and ground transmitters. Regulators must balance commercial demand for frequencies with the need to preserve “radio quiet” conditions in protected zones where instruments like ASKAP and future SKA antennas operate.skao.int+1

Public interest in mysterious space signals sometimes veers toward speculation about extraterrestrial intelligence. While FRBs are almost certainly natural phenomena, communicators and researchers have to present findings clearly, avoiding sensationalism while still engaging the public.Wikipedia+1

Geopolitical and Security Implications

The science of FRBs is part of a wider landscape where countries invest in large-scale research infrastructure as a marker of scientific capability. International collaborations on radio astronomy—spanning Australia, South Africa, Europe, North America, and beyond—can strengthen diplomatic ties and shared technical standards.sarao.ac.za+2skao.int+2

At the same time, some technologies used in radio astronomy, such as advanced antennas and signal processing, overlap with defense and communications applications. Ensuring open, peaceful use of these tools, while respecting export controls and security regulations, is an ongoing balancing act.

Why This Matters

FRB 20220610A matters for three main reasons.

First, it extends FRBs to roughly half the age of the universe. Because the burst is so distant, its signal samples vast stretches of intergalactic space. When astronomers compare its dispersion measure to its redshift, they can test models of how much ordinary matter—protons and neutrons—lies between galaxies. That, in turn, helps resolve a long-standing puzzle about “missing” baryons that do not show up in traditional surveys.scienceinpublic.com.au+1

Second, the burst challenges assumptions about how powerful FRBs can be. Any model for their engines must now explain events that push above earlier predicted energy caps without tearing their source objects apart or violating basic physics.Wikipedia+2Nature+2

Third, the detection highlights the rapid progress in time-domain astronomy. Just over a decade ago, FRBs were an oddity. Now they are a growing population of precisely localized events, with some tied to individual stellar environments and others to complex galaxy systems. Record-setters like FRB 20220610A signal that the field is entering a phase where FRBs can be used as standard tools, not just mysteries.NASA Science+2Live Science+2

For readers, the key message is that tiny, fleeting signals can answer large questions. They show how careful measurement and patient cross-checking can turn what looks like noise into a map of the universe’s structure.

Real-World Impact

The practical impact of FRB 20220610A unfolds in several domains:

One example is the development of more capable radio observatories and data centers. Facilities built to chase FRBs must detect weak, short-lived events in massive data streams, then alert other telescopes within seconds to minutes. The same architecture can support rapid response to other transient events, from solar storms to satellite anomalies.

Another example lies in training and collaboration. FRB studies draw together radio astronomers, optical observers, theorists, and data scientists. Graduate students and early-career researchers learn to work across instruments and continents, strengthening the broader scientific workforce.

A third example is public engagement. Record-breaking bursts that predate the solar system make abstract cosmological timescales tangible. Museums, planetariums, and online science communicators increasingly use FRBs as entry points to explain concepts like redshift, cosmic expansion, and the life cycle of stars.

Finally, the methods used to interpret FRB 20220610A—inferring unseen material from its effect on passing light—mirror techniques used closer to home. Similar approaches help characterize the plasma environment around Earth, model how signals propagate through the ionosphere, and refine communication links with spacecraft. The conceptual tools are the same, even if the distances are wildly different.Universe Today+1

Conclusion

At the heart of this story is a simple contrast in scale. FRB 20220610A lasted for a few thousandths of a second. Yet it traveled for 8 billion years, crossed enormous cosmic structures, and carried with it a detailed record of the matter it encountered along the way.

If events like this continue to be found and mapped, FRBs could become routine instruments for weighing the universe: fast, bright flashes that turn empty-looking space into a measurable medium. The same data will help narrow down which exotic engines—magnetars, mergers, or something else—are capable of such violent outbursts.scienceinpublic.com.au+2Wikipedia+2

Looking ahead, the key signals to watch are straightforward. New radio arrays and upgrades should increase the number of well-localized FRBs each year. Space- and ground-based optical telescopes will refine host galaxy identifications, while theory will race to keep up with the expanding energy and distance range of known bursts.

Whether FRB 20220610A remains a record-holder or is soon surpassed, it has already established a benchmark: a millisecond-long flare, older than the solar system, that turns the faint whisper of deep space into a powerful probe of the universe’s hidden structure.