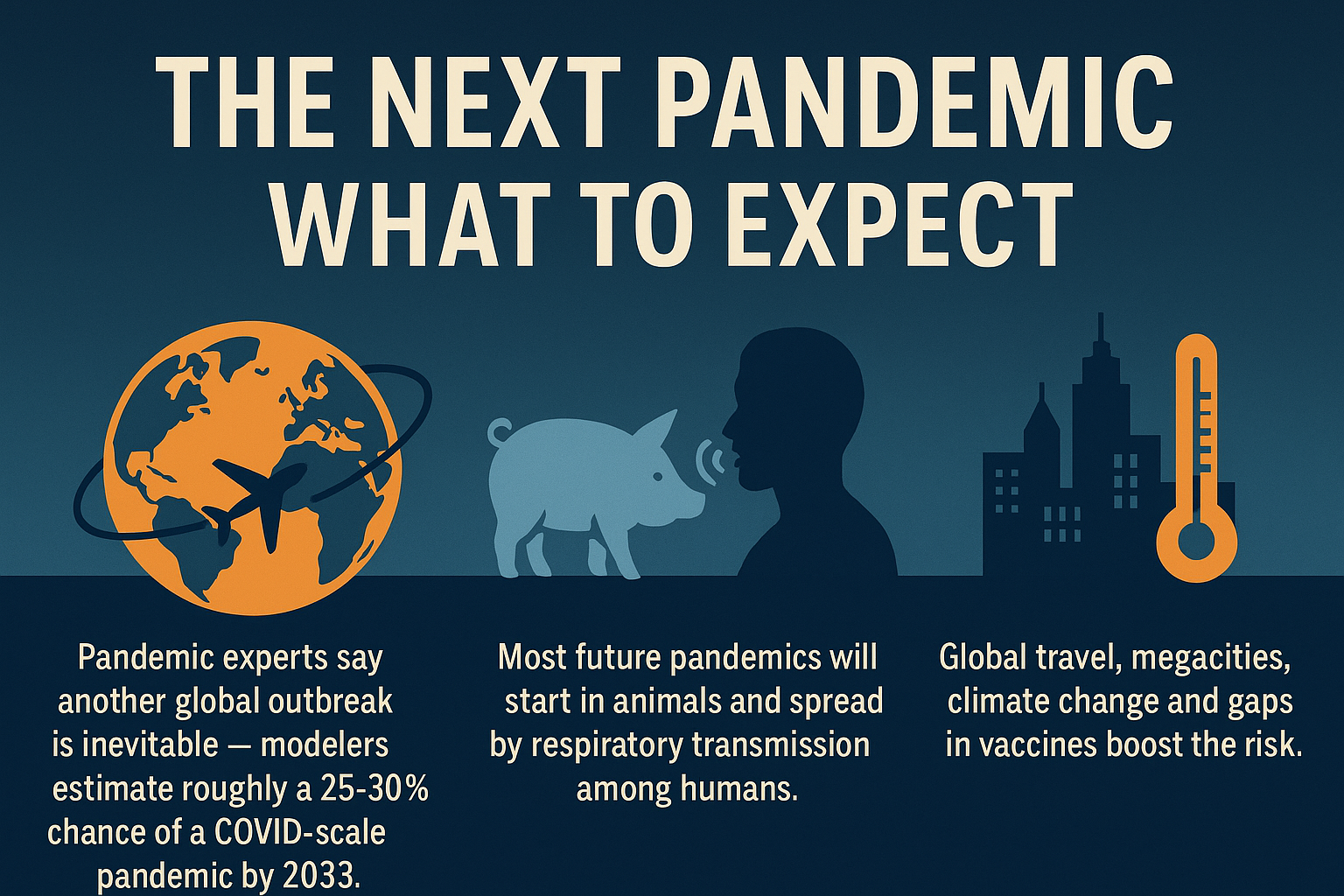

The Next Pandemic: What to Expect

A global outbreak on par with COVID-19 is no longer a question of if, but when.

Experts warn there is roughly a 25–30% chance of another pandemic of similar scale within the next decade.

The trigger will likely be a virus jumping from animals to people and spreading swiftly through our connected world.

Climate change, dense cities and frequent air travel only heighten the danger. In short: the next pandemic is on the horizon, and preparation is critical.

Summary

Pandemic experts say another global outbreak is inevitable — modelers estimate roughly a 25–30% chance of a COVID-scale pandemic by 2033.

Most future pandemics will start in animals and spread by respiratory transmission among humans.

Global travel, megacities, climate change and gaps in vaccines boost the risk.

Scientists rank influenza viruses, unknown “Disease X” pathogens, Ebola-like fevers, avian flu (H5N1) and antibiotic-resistant superbugs as top threats.

Background

History is a harsh teacher. In 2003, SARS showed how one virus could circle the globe. In 2009 a new flu (H1N1) reached dozens of countries in weeks. The 2014–16 Ebola outbreak grew from one village to over 28,000 cases, overwhelming clinics. In 2020, COVID-19 shut down travel worldwide.

Each time, experts sounded alarms and coined “Disease X” for any unknown virus that could spark the next pandemic.

All this history points to clear patterns. We live in a densely connected world. Air travel, trade and online commerce tie every region together. As cities spread into farms and forests, humans encounter new animals and their germs. Combined with climate shifts that push insects and rodents into new areas, the conditions for a pandemic keep growing. The next outbreak could spark anywhere — and blaze out of control if it catches us unprepared.

Core Analysis

Pandemics exploit modern life. No corner of the world is isolated anymore. People and goods move globally. Key risk factors include:

Global travel and trade: Airplanes and ships now link every continent. A person can carry a virus halfway across the world in a single day.

Urbanization and animal contact: Cities and suburbs often spill into farms and forests. Markets and megafarms mix people with livestock and wildlife, making it easy for animal viruses to jump into humans.

Climate change: Warmer weather, floods and droughts are driving mosquitoes, ticks and rodents into new regions. Diseases once confined to the tropics — like dengue and Zika — are moving into cities that have never seen them.

Gaps in health systems: Many pathogens have no vaccines or treatments. When a new microbe spreads, the lack of tools gives it a head start. Hospitals and labs already strain under routine illnesses, so a big new outbreak could overwhelm them quickly.

The most likely pandemic culprits can be ranked by their risk. Here are ten top threats:

Influenza viruses. The top threat. Flu viruses mutate constantly. History shows birds and pigs often pass new flu strains to humans. Seasonal flu outbreaks are mild rehearsals; a novel strain could be far worse. Dense transport networks mean a new flu could race around the globe before anyone notices. Existing flu vaccines might not match it, forcing a scramble to make new shots in real time.

Disease X (unknown pathogen). This wildcard is any virus or microbe not yet discovered. By definition it would be a surprise. It could be a new respiratory virus from wildlife (or even a lab accident). We cannot prepare a specific vaccine in advance, so the strategy must be broad surveillance and flexible response plans.

Coronaviruses (SARS-like viruses). COVID-19 is not the last coronavirus threat. Bats and other animals carry many coronaviruses that could adapt to people. A new SARS or MERS variant — or a radical mutation of COVID — could emerge and spread fast. Hospitals are already under strain; a rapidly spreading coronavirus could topple them again.

Ebola and other hemorrhagic fevers. Viruses like Ebola, Marburg and Lassa kill 30–90% of patients and cause frightening symptoms. They have caused deadly outbreaks in parts of Africa. If one of these viruses reached a city or was carried by an air traveler, the impact would be huge. We have a few vaccines and some experience, but large outbreaks still overwhelm response efforts.

Avian influenza (H5N1 and others). Bird flu has devastated poultry worldwide and has occasionally infected people who handle sick birds, often fatally. So far it doesn’t spread well human-to-human, but if it mutates to do so, every farmworker and poultry plant becomes a launchpad. Millions of migratory birds and dense poultry farms provide repeated spillover chances. A human-adapted avian flu could trigger a major pandemic.

Drug-resistant bacteria (superbugs). Antibiotic-resistant pathogens are a creeping crisis. Already, MRSA, drug-resistant tuberculosis and other superbugs kill thousands of people each year. Imagine an everyday infection (like pneumonia or a wound infection) that resists all antibiotics. Routine surgeries, chemotherapy and childbirth would become perilous. The health system’s built-in “shock absorbers” could break under such pressure.

Nipah virus. Nipah hides in fruit bats of South Asia and causes encephalitis with a 40–75% death rate. It can spread from bats to pigs to humans, and between people in close contact. It’s rare now, but one infected individual or a mutation could ignite a larger outbreak in dense populations.

Lassa fever. Carried by rats in West Africa, Lassa causes hemorrhagic fever and kills about 20% of hospitalized patients. It infects thousands each year with mostly mild symptoms, but a large urban outbreak (or spread beyond its home region) would pose a serious challenge. No licensed vaccine exists.

Arboviruses (dengue, Zika, chikungunya, etc.). Mosquito-borne viruses already infect millions annually. Dengue alone causes hundreds of deaths daily in the tropics. A new mutation or unchecked spread into temperate zones could trigger an epidemic. As climate change expands mosquito ranges, diseases once limited to the tropics can appear far away.

Other emerging threats. This catch-all covers pathogens like Rift Valley fever, hantaviruses or drug-resistant fungi. It also includes even known diseases (like measles or polio) if vaccination gaps grow. Essentially, any deadly microbe with the ability to travel between people can climb this list.

Tropical mosquitoes like Aedes carry dengue, Zika and chikungunya. Warmer winters and heavy rains let them survive in new regions. This lets mosquito-borne diseases reach places with unprepared health systems.

Why This Matters

A pandemic impacts society at every level. Economically, it can shutter factories, interrupt trade and cost millions of jobs. Travel bans and lockdowns stall the global supply chain: stores run empty and industries grind to a halt. Politically, governments may close borders or rush to secure vaccines, which can spark international tensions and blame games.

For individuals, daily life changes. Schools and events may close, and routine gatherings are canceled. People scramble for medicines and vaccines, and hospitals prioritize emergencies over normal care. Technology and science move into overdrive: researchers will sequence the pathogen’s genes faster, improve outbreak-tracking systems, and sprint to develop new vaccines and treatments. But these solutions take time.

Communities and individuals must also adapt. Habits like wearing masks in flu season, washing hands frequently, and staying home when sick become important again. Trust in public health advice and global cooperation become crucial. Every individual’s choices matter too — getting seasonal vaccines and avoiding crowds when ill can help slow an outbreak.

Real-World Examples

2009 H1N1 (Swine Flu): A new flu emerged in Mexico and jumped on planes, reaching dozens of countries within weeks. It eventually caused tens of thousands of deaths worldwide, showing how fast influenza can spread and kill.

2014–2016 West Africa Ebola: The virus began with a single case in rural Guinea but exploded into an epidemic of over 28,000 cases across multiple countries. Local hospitals collapsed under the load, proving that even remote outbreaks can become international crises.

2023 Avian Flu (H5N1): This bird flu circulated widely in poultry farms on several continents. Millions of chickens and ducks were culled to stop it. A few farm workers caught the virus, reminding us that animal flu viruses can jump into people at any time.

2020 COVID-19: Novel coronavirus infections quietly spread in Wuhan before anyone knew what was happening. Within months it hit every continent, illustrating how a few flights can seed a global pandemic before travel restrictions even begin.

2015–2016 Zika Virus: Once limited to Africa and Asia, Zika spread rapidly through the Americas by 2016. It caused thousands of cases of birth defects in newborns, showing how quickly a mosquito-borne virus can appear in new regions.

Mosquito range shifts: In recent years, warmer winters have let Aedes mosquitoes survive longer in parts of Europe and the U.S., leading to local outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya in places previously free of those diseases. Each example shows how quickly a local outbreak can escalate in our interconnected world.

These examples reinforce a simple truth: pathogens travel fast in today’s world. History and science both warn that the next pandemic is likely coming. Being ready means strengthening health systems, funding research, and staying globally coordinated. All of these preparations affect every one of us, since the next outbreak anywhere can become a problem everywhere.