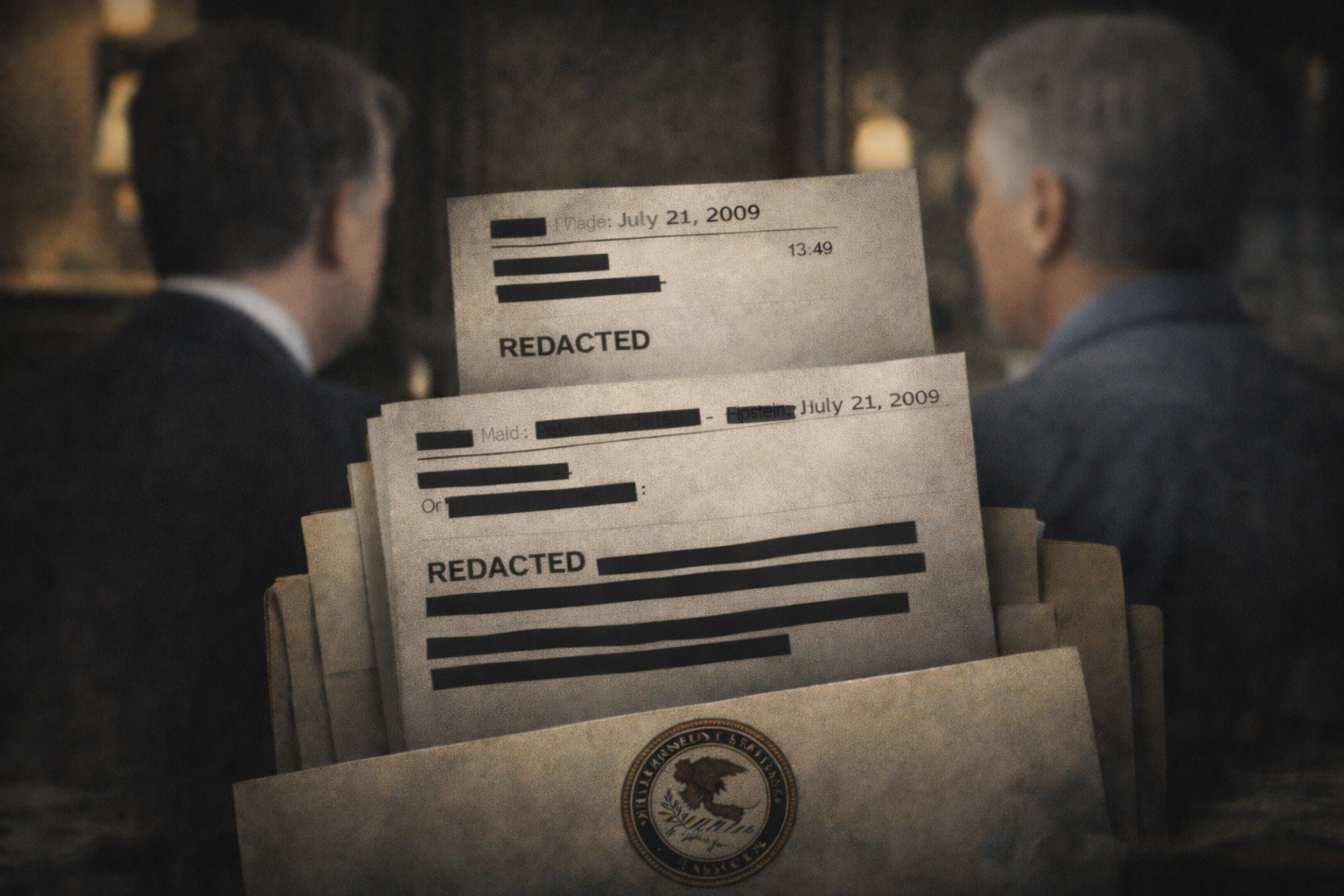

Mandelson Joked With Epstein After Jail—and the Emails Are Now a Political Time Bomb

Peter Mandelson Epstein Emails: 2009 Jokes After Jail Release

2009 emails show Mandelson joking with Epstein after his jail release, and the story is now procedural.

A new tranche of Epstein-related emails is reshaping the Peter Mandelson controversy in a way that goes beyond reputational damage. The core claim is simple: after Jeffrey Epstein’s 2009 release from jail, Mandelson stayed in touch, and the tone of the correspondence included joking and intimacy that reads as staggeringly misjudged given what Epstein had been convicted of.

That alone is politically toxic. But the more consequential shift is what happens when private messages and government-era exchanges start interacting with formal vetting, official records, and police thresholds.

The story turns on whether the emails are merely humiliating—or whether they establish a provable chain linking a senior minister’s conduct to state decisions, market-sensitive information, and the integrity of government processes.

Key Points

The latest disclosed emails place Mandelson in contact with Epstein after Epstein’s 2009 release, with language that has intensified public and political backlash.

Separate messages in the same broader disclosure period appear to show Epstein providing money to Mandelson’s husband for expenses, raising questions about judgment, disclosure, and the boundary between personal and improper benefit.

Some of the most serious exposure is no longer about tone; it is about whether confidential government material was shared during Mandelson’s time in office and whether that reaches a criminal threshold.

The focus of political pressure has shifted from asking "Why was he close to Epstein?" to asking "Who knew what, when—and what did the vetting process record?"

The government’s next moves are constrained by process: document handling, national security redactions, parliamentary demands, and the fact that police can act on evidence once it is in the open.

Mandelson has responded by disputing or distancing himself from parts of the material and expressing regret about the association, but the institutional machinery does not pause for contrition.

Background

Jeffrey Epstein pleaded guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida involving soliciting and procuring a minor for prostitution, served time in jail, and was released in 2009 under conditions that still allowed him to maintain contacts and resume influence-seeking behavior.

Peter Mandelson is a long-standing UK political operator who held senior cabinet roles, including as business secretary during the post-financial-crisis period. That timing matters: the policy environment then involved high-stakes decisions on banks, fiscal stability, and market confidence.

The new wave of attention stems from the continuing release of Epstein-related material by US authorities. In this cycle, the disclosures have combined three ingredients that are combustible together: personally intimate messages, financial references involving Mandelson’s household, and apparent sharing of government-facing information.

Analysis

Why the 2009 timing changes the moral and political math

A politician can argue poor judgment in a friendship formed before a conviction. The argument collapses when the contact continues after conviction and after prison. The public read is blunt: by 2009, the risk signals were not subtle.

That is why jokes, affectionate sign-offs, and “normal” social chatter after release are not just embarrassing. They are evidence of normalization—of treating a convicted offender as socially rehabilitated within elite networks long before any public accountability.

Scenarios now look like this:

One path is that the emails are treated as a moral scandal that burns hot and then fades. Another path is that they are framed as proof of a sustained relationship that made later decisions—appointments, access, introductions—negligent.

The signpost to watch is whether political demands focus on apology and resignation or on formal disclosures of the internal processes recorded at the time.

The financial thread: not the amount, the mechanism

In isolation, money moving around an ecosystem of wealthy people is not a unique headline. In context, it becomes a governance problem.

When emails and records point to Epstein paying expenses connected to Mandelson’s husband after Epstein’s release, it raises three practical questions that investigators and officials tend to care about far more than the gossip layer:

First, was the support disclosed appropriately, and to whom? Second, how was it characterized—loan, gift, reimbursement—and does that characterization match the documentary reality? Third, did any benefit create an obligation, explicit or implied, that could color access or decision-making?

Two plausible scenarios emerge. In the low-impact scenario, it is judged as personal foolishness without provable quid pro quo. In the high-impact scenario, the financial links are used to establish motive, leverage, or compromised judgment when paired with policy-related exchanges.

The signposts are whether investigators begin narrowing to specific transactions and whether political opponents stop arguing “it looks bad” and start arguing “it fits an inducement pattern.”

The policy thread: “market-sensitive” is a legal trigger phrase, not a metaphor

The most dangerous allegations are not jokes. Epstein may have received confidential government information during a period of market and public finance volatility.

Interpreting messages as sharing internal assessments, strategies, or draft positions transforms the issue from ethics to enforcement reality. This is where institutions behave differently. Civil service systems, security culture, and policing decisions are built around the principle that certain categories of information are protected regardless of whether the individual intended harm.

There are several scenario branches here. One is that what was shared is judged too general to matter. Another is that it is judged sensitive enough to breach standards but not laws. The escalatory branch is that it meets the threshold for criminal investigation because the substance, timing, and seniority make it hard to wave away.

The signpost is whether police statements and parliamentary language begin to converge on specific documents, dates, and descriptions rather than broad outrage.

The political blast radius: this is now a test of the appointment system

Once a scandal attaches to an appointment or a role, it rarely remains about the individual. It becomes about process credibility.

If the government was aware of post-conviction contact before making key decisions related to Mandelson, it creates a procedural story: what did vetting flag, what answers were given, who signed off, and what was recorded?

That matters because procedural stories don’t die with a single resignation. They expand. Each new disclosure invites a retrospective audit: not only “was this person suitable?” but “does the system work at all when the subject is powerful?”

Two plausible political scenarios are emerging. In one case, the government contains it by releasing a limited record, drawing a line under it, and betting that the public will move on. In the other, the pressure forces fuller disclosure and sparks an internal accountability cascade.

The signpost is whether the fight becomes about document release and parliamentary mechanisms rather than about personal morality.

What Most Coverage Misses

The hinge is that the scandal is migrating from reputational damage into an evidence-handling and accountability pipeline that has its own momentum.

The mechanism is simple: once the controversy is forced into formal channels—police review, parliamentary demands for records, and the bureaucratic trail of vetting—the question is no longer “how awful is this?” but “what can be proven, and who signed what?” This shifts incentives. Officials become risk-averse. Politicians stop defending character and start defending paperwork. Investigators start looking for corroboration, not commentary.

What would confirm these developments in the next days and weeks is (1) a shift from general calls for transparency to specific demands for specific documents and (2) any indication that police interest is narrowing to defined episodes—particular emails, particular memos, particular transfers—rather than the broader relationship.

What Changes Now

Mandelson, his close associates, and the institutions that supported or processed his appointments are the most affected. This is where accountability gets redistributed: even if the original misconduct is personal, the system’s response becomes political.

In the short term (the next 24–72 hours and coming weeks), the story is likely to be driven by document pressure, statements calibrated around legal risk, and the slow emergence of “who knew what when” timelines.

In the long term (months), the consequences look like structural reform debates: vetting standards for senior appointments, rules around disclosure of gifts and loans, and tighter discipline on ministerial communications—because once the public sees elite networks operate with casual intimacy around a convicted offender, the demand becomes systemic, not personal.

The key “because” mechanism is that process failures are easier to prosecute politically than moral failures: you can argue about feelings, but you can audit forms, emails, decisions, and redactions.

Real-World Impact

A civil servant in a sensitive department watches this and learns a blunt lesson: everything becomes discoverable eventually, so informal sharing is career poison.

A corporate executive weighing whether to engage the government informally becomes more cautious because the reputational cost of proximity to scandal now looks immediate and permanent.

A policy team working on financial stability messaging becomes tighter and slower because leaks—real or alleged—force defensive workflows, approvals, and legal review.

An ordinary voter sees “elite impunity” as the theme, not “one bad actor,” and that accelerates cynicism toward public institutions during an already trust-poor era.

The Paper Trail Problem That Won’t Go Away

This scandal is no longer primarily about how Mandelson sounded in private. It is about how power behaves when it thinks nobody is watching—and what happens when the archive opens.

The fork in the road is clear: either the government treats the case as a bounded episode and survives by controlling disclosure, or the procedural demands widen until the system itself is on trial—vetting, titles, appointments, and the informal networks that sit behind them.

Watch for concrete signposts: targeted requests for specific files, formal investigative narrowing to named documents or transactions, and any escalation from political condemnation into institutional action that cannot be reversed with a statement.

The state loses credibility when private intimacy and public office collide.