Japan’s 7.5-Magnitude Earthquake: Tsunami Warning Lifted, Risk Questions Remain

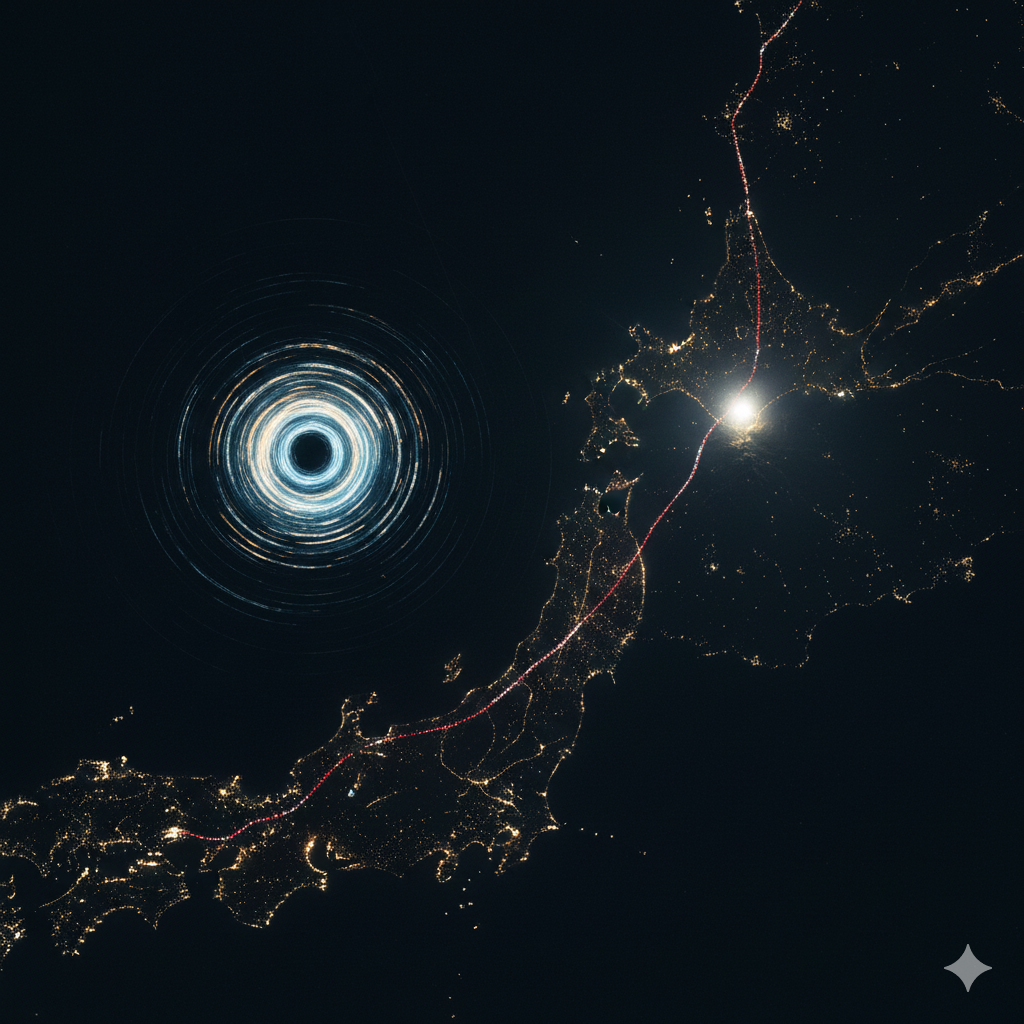

Late on a December night, a powerful 7.5-magnitude earthquake shook northern Japan, sending residents scrambling to higher ground as tsunami sirens sounded along the Pacific coast. Waves of up to around 70 centimeters reached parts of Hokkaido and the Sanriku shoreline, before a full tsunami warning was lifted hours later. Dozens of people were injured, but there were no reports of widespread destruction or deaths in the first wave of assessments.

The immediate danger has eased, yet the psychological and practical shock is still unfolding. Around 90,000 people were told to evacuate, rail services were halted, and power briefly went out for thousands of homes in the region. Coastal communities now face the familiar tension that follows a major quake in Japan: relief that the worst did not happen, and anxiety that this might only be a warning shot.

This piece looks at what is known so far about the earthquake and the now-lifted tsunami warning, how Japan’s early-warning and evacuation systems performed, and what scientists are saying about aftershock and megaquake risks in the coming days. It also explores the broader political, economic, and social dimensions of yet another major seismic event in one of the world’s most earthquake-prone countries.

By the end, the reader will have a clearer sense of what has actually changed, what remains uncertain, and what signals to watch in the days ahead, from aftershocks to policy debates on coastal safety and nuclear security.

The story turns on whether this episode is remembered as a near-miss or an early warning of something larger.

Key Points

A 7.5-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Aomori Prefecture late at night, with strong shaking felt across northern Japan.

Tsunami warnings and advisories were issued for parts of Hokkaido, Aomori, and Iwate, with observed waves of around 20–70 centimeters before the warnings were lifted.

Authorities ordered or advised evacuations affecting roughly 90,000 people, suspended bullet trains and local rail lines, and carried out overnight damage checks.

At least 30–33 people were reported injured, mostly by falling objects and debris, but there were no early reports of large-scale building collapse or fatalities.

Nuclear facilities in the region reported no critical safety issues, though one fuel reprocessing plant logged a limited water spill within normal safety margins.

Seismologists warn of a heightened risk of strong aftershocks and even a larger event along the northeastern coast in the coming week.

The quake has revived memories of the 2011 disaster and raised questions about whether Japan’s coastal defenses and public preparedness are keeping pace with rising risk.

Background

Japan sits on the seismically active “Ring of Fire,” where several tectonic plates meet and grind against each other. That geography exposes the country to frequent earthquakes, including occasional powerful offshore events that can generate tsunamis. The latest quake struck in the Pacific Ocean about 80 kilometers off Aomori Prefecture at around 11:15 p.m. local time, at a depth of roughly 40–50 kilometers.

Japan’s meteorological agency initially estimated the magnitude slightly higher, around 7.6, before settling around 7.5. The shaking reached “upper 6” on Japan’s seven-level intensity scale in Hachinohe, a level strong enough to move heavy furniture and damage older or poorly reinforced structures.

Within minutes, coastal areas of Hokkaido, Aomori, and Iwate were under tsunami warnings and advisories, with initial forecasts suggesting waves up to three meters in some locations. That triggered local evacuation orders and late-night sirens across multiple municipalities. In practice, observed tsunami heights were significantly lower, in the tens of centimeters, but still strong enough to create dangerous currents and justify keeping people off beaches and harbors.

By early morning, the authorities had downgraded the alerts and then lifted all tsunami advisories for the affected Pacific coastline. As damage reports came in, the picture that emerged was one of scattered injuries and local disruption rather than national catastrophe. Yet the event fits a pattern: a major offshore quake along a coastline that has already seen some of the worst tsunami damage in modern history, including the 2011 disaster that killed nearly 20,000 people and triggered the Fukushima nuclear crisis.

Analysis

Political and Geopolitical Dimensions

Domestically, the quake is an early test for Japan’s current leadership on disaster readiness. The prime minister quickly convened an emergency task force and framed the response around protecting lives and restoring services. That swift, visible coordination is politically important in a country where memories of earlier crises, including 2011, still shape public expectations of the state.

If subsequent assessments show gaps in evacuation procedures, communication, or infrastructure resilience, opposition voices are likely to press for inquiries, especially on issues such as coastal defenses, hospital surge capacity, and the robustness of power and transport networks in the north. Local governors and mayors in affected prefectures may also use the moment to push for more central funding for seawalls, early-warning upgrades, and community shelters.

Internationally, the quake does not immediately alter Japan’s geopolitical position, but it reinforces a theme that already influences security planning: the need to manage natural-disaster risk alongside traditional military threats. Allies that rely on Japanese ports, shipyards, and semiconductor-related infrastructure will be watching for signs of vulnerability in the event of a larger quake or a compound crisis.

Economic and Market Impact

Financial markets tend to react quickly to unexpected natural disasters in Japan. Early reports suggested a brief weakening of the yen as traders weighed the possibility of larger damage, followed by some stabilisation as it became clear that the tsunami was limited and nuclear facilities were operating safely.

The more meaningful economic effects may show up locally rather than nationally. Transport disruptions, including halted bullet trains and suspended regional lines, stranded passengers and delayed freight overnight. Depending on how quickly services are fully restored, there could be knock-on impacts for just-in-time manufacturing, especially in sectors that depend on components from northern suppliers.

Insurance assessments will take longer. If damage remains limited to cracked roads, fallen shelves, and localised structural issues, the financial hit will be modest compared with past megaquakes. But if inspections uncover deeper problems—such as damage to port facilities, industrial plants, or critical logistics hubs—the event could still bring a noticeable, if contained, bill.

Social and Cultural Fallout

For residents of northern Japan, the most immediate effect is emotional rather than financial. Being jolted awake by a major quake, hearing tsunami sirens, and rushing to higher ground revive memories many hoped to leave behind. Coastal communities that lived through 2011 are particularly sensitive to even modest tsunami forecasts.

The evacuation of tens of thousands of people, including elderly residents and families with young children, puts pressure on local shelters and on the social fabric. People spend long, anxious hours in gyms, schools, and public buildings, juggling work, caregiving, and limited sleep. If aftershocks continue, the psychological strain can linger long after the physical damage is repaired.

There is also a cultural dimension to how swiftly life resumes. Schools reopening, trains restarting, and shops trading again signal resilience, but they can also mask quiet exhaustion. In some towns, younger residents may see the quake as one more reason to consider leaving vulnerable coastal areas, reinforcing long-term demographic shifts away from rural regions already struggling with aging and depopulation.

Technological and Security Implications

Japan’s reputation for advanced earthquake and tsunami monitoring is central to how this event is judged. The meteorological agency issued alerts quickly, and the combination of early-warning messages, sirens, and broadcast interruptions likely reduced the risk of casualties along the coast. At the same time, evacuating at night in winter conditions is inherently difficult, especially for older people and those without cars.

On the nuclear side, the early confirmation that no major anomalies were found at nearby facilities was crucial for public confidence. The reported water spill at a fuel reprocessing plant—within normal ranges and without a safety impact—highlights how closely these sites are monitored after even modest tsunamis.

Technologically, the quake will feed back into hazard models. Seismologists are already warning of an increased short-term probability of a larger event along the same stretch of coast, and that message relies on continuously updated data from dense sensor networks offshore and on land.

What Most Coverage Misses

Much early coverage focuses on the headline numbers: magnitude, wave height, evacuations, injuries. What tends to get less attention is how these repeated “moderate” disasters accumulate over time, especially for smaller coastal towns. Even when buildings stay standing, each event can erode savings, accelerate population decline, and make it harder for local economies to compete.

Another under-examined angle is the long-term cost of maintaining high levels of preparedness. Sirens, seawalls, emergency drills, reinforced schools, and real-time monitoring systems all require steady investment and political will. When an event like this ends with “only” dozens of injuries, there is a temptation—both for taxpayers and politicians—to question the expense. Yet those same systems are what stand between a disturbing night and a national tragedy.

Finally, there is the question of compound risk. Climate change is altering sea levels and storm patterns, while seismic risk remains constant or, in the short term after a major quake, elevated. Coastal defenses and evacuation plans built for historical baselines may not fully reflect the combined impact of higher seas, stronger storms, and repeat quakes over the coming decades. This quake fits into that longer story, even if its immediate damage is limited.

Why This Matters

In the short term, the people most affected are residents of northern coastal prefectures who endured strong shaking, spent the night in shelters, and now face days of aftershocks and inspections. Transport operators, local businesses, and hospitals are assessing damage and catching up on delayed services.

Over the longer term, the quake feeds into national debates about where people live, how infrastructure is built, and how much risk society is prepared to tolerate along exposed coastlines. For a country with an aging population and tight public finances, deciding which towns to fortify, which to gradually relocate, and how to share the cost is a politically sensitive balancing act.

Globally, the event is another reminder that critical industrial and technological supply chains run through hazard-prone regions. Any serious damage to ports, factories, or energy facilities in northeastern Japan would ripple outward, affecting everything from auto parts to electronics. Even when the damage is limited, each incident reinforces the need for companies and governments to plan around seismic risk in their resilience strategies.

In the coming days, key milestones to watch include updated damage and casualty counts, aftershock patterns, any revisions to official risk assessments, and political statements on coastal and nuclear safety. If seismologists see signs that stress is migrating along nearby faults, warnings about a potential larger event could sharpen.

Real-World Impact

A hotel manager in Hachinohe spent the night guiding guests down stairwells as ceiling tiles fell and alarms sounded. By morning, they had to juggle cancellations from nervous travelers with the practical work of checking for cracks, leaks, and loose fixtures before reopening.

A fisherman in a small port town in Hokkaido moved his boat to deeper water when the first tsunami alerts appeared, then stayed awake through the night checking tide charts and radio updates. Even though the waves turned out to be less than a meter, he lost a day’s catch and faces repair costs for moorings strained by unusual currents.

A nurse in a coastal hospital had to comfort elderly patients shaken by both the tremors and the sirens, while the facility switched to backup generators during brief power interruptions. The staff rehearsed evacuation plans for intensive-care patients in case the tsunami warning escalated, then reversed those preparations when the alert was lifted.

A local official in Aomori spent hours fielding calls from residents who wanted to know whether they could safely go home, all while coordinating with national agencies on aftershock guidance. Now, that official must help the community process both relief and lingering fear, and prepare them for the possibility that more quakes could follow.

Road Ahead

Japan’s latest 7.5-magnitude earthquake and the short-lived tsunami warning appear, at first glance, to be a close call rather than a catastrophe: dozens injured, some damage and disruption, but no nationwide emergency. That impression is both reassuring and incomplete. The event has once again exposed how much of the country’s population, infrastructure, and sense of security rests on fragile ground—literally and figuratively.

The core tension now is whether policymakers and the public treat this as a one-night scare or as part of a broader pattern that demands sustained investment and, in some cases, difficult choices about where and how people live. The trade-off is familiar: the cost and disruption of stronger defenses and smarter planning versus the potentially far higher cost of being unprepared for the next, possibly bigger, event.

In the days ahead, early clues will come from aftershock activity, updated scientific briefings on regional fault stress, and political signals about disaster funding and coastal safety. If those signals point toward serious, long-term planning rather than a return to business as usual, this quake may be remembered less for the waves it produced and more for the changes it set in motion.