What If Nazi Germany Developed the Nuclear Bomb First?

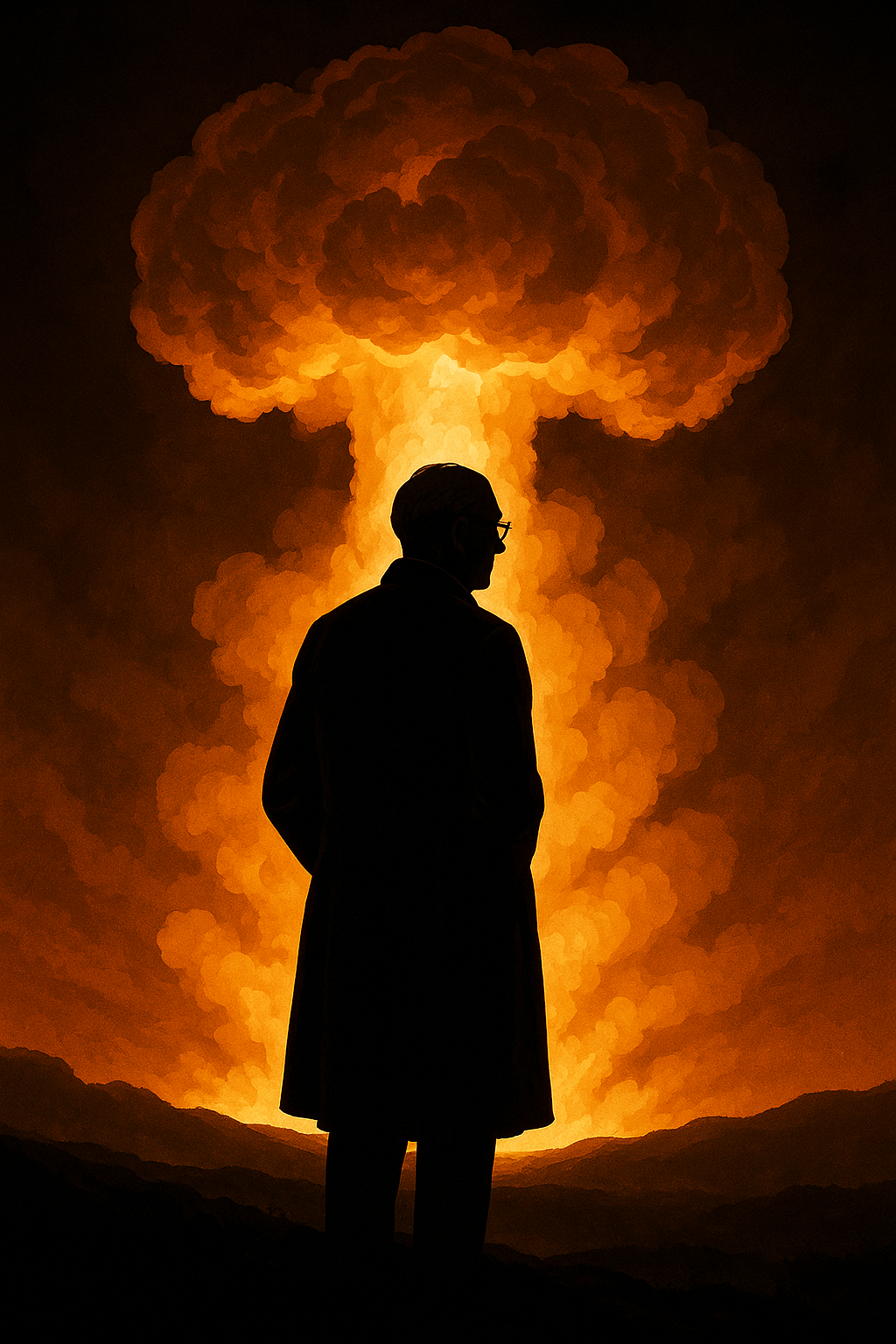

Imagine a gray dawn over London or Moscow in 1944. No air raid sirens, no fleets of bombers overhead. Just a blinding flash, a rising column of fire, and a mushroom cloud clawing its way into the sky. In that moment, the Second World War and the entire twentieth century would tilt onto a different track.

In reality, Nazi Germany began exploring nuclear fission early but never came close to a working atomic bomb. The first nuclear test was conducted instead by the United States in July 1945, followed by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ushering in the nuclear age under American, not German, control.

This article asks a stark counterfactual: What if the Nazis had developed the nuclear bomb first and fielded it during the war? It explores what would have needed to change inside the German program, how Hitler might have used the weapon, and whether it could have secured a Nazi victory. It then looks forward: if a genocidal dictatorship had been the first nuclear superpower, how different might today’s world order, alliances, and nuclear norms look?

The analysis separates established historical facts about the wartime nuclear race from mainstream interpretations and, finally, from informed speculation about a very different—and much darker—nuclear century.

Key Points

Nazi Germany started work on nuclear fission early in the war but, in reality, never came close to a usable bomb because of scientific errors, resource limits, and regime choices.

The United States ultimately tested the first nuclear device in July 1945 and used atomic bombs against Japan, shaping a postwar order dominated by an American–Soviet nuclear rivalry.

For Germany to get the bomb first, the regime would have needed to prioritize the project, keep key scientists together, solve reactor and enrichment problems, and protect the industry from Allied disruption.

In a plausible scenario, a small number of German bombs would be used against London or Soviet targets, aiming to force a political settlement rather than to annihilate every enemy city.

Most historians doubt that even a handful of Nazi bombs would guarantee total victory; instead they might produce a brutal nuclear stalemate, a negotiated peace, or a delayed but still decisive Allied response.

A world where Nazi Germany survived as a nuclear superpower would likely see entrenched totalitarian rule in Europe, different borders, a harsher global arms race, and a very different moral narrative about nuclear weapons.

All such outcomes are speculative; they highlight how contingent the real nuclear timeline was, and how much depended on scientific decisions, resource choices, and the politics of authoritarian power.

Background

By the late 1930s, nuclear physics was transforming fast. In 1938, scientists in Germany helped identify nuclear fission, the splitting of the atom that releases enormous energy. Within months, German military authorities created a secret research effort, sometimes called the “uranium club,” to explore military uses of fission.

Nazi Germany seemed well placed at first. It had strong universities, industrial capacity, access to uranium, and some of the world’s leading theoretical physicists. Yet several structural and political choices quickly undermined that advantage. Jewish and politically suspect scientists were expelled or fled abroad. Projects were split into rival groups. Funding was limited and inconsistent compared with other “wonder weapons” like rockets and jet aircraft.

Crucially, German teams made technical missteps. They rejected graphite as a possible moderator for nuclear reactors, focusing instead on scarce heavy water. They underestimated the engineering and industrial scale required to enrich uranium or produce plutonium. At high levels of the regime, the bomb was often seen as too slow or too uncertain to matter for a war that leaders expected to win quickly.

On the Allied side, fear that Germany might race ahead helped spur the much larger Manhattan Project in the United States. With vast resources, centralized management, and support from émigré scientists, that project moved from theory to test device in a few years. On 16 July 1945, the first nuclear explosion was detonated in the New Mexican desert.

In this real timeline, the Third Reich collapsed before any nuclear weapon appeared on a battlefield in Europe. The bomb instead shaped the end of the war against Japan and framed a postwar nuclear order dominated by the United States and the Soviet Union.

The counterfactual question—what if Nazi Germany had got there first—starts by asking what would have needed to go differently inside that early German program.

Analysis

How Nazi Germany Might Have Got the Bomb First

To imagine a successful German bomb program, several major variables must shift from the historical record.

First, the regime would need to treat nuclear weapons as a central war priority from 1939 onward. That means sustained funding, protection from constant reshuffling, and a clear military chain of command rather than fragmented academic projects. The leadership would have to believe that a war-winning weapon might be ready only in the mid-1940s and still consider that worthwhile.

Second, the scientific talent pool would need to remain intact. In reality, the expulsion or flight of Jewish and dissident scientists stripped Germany of key expertise. A counterfactual path assumes that the regime either moderates this persecution in the short term or, more cynically, coerces and concentrates remaining experts in a heavily resourced program.

Third, the technical path must be chosen correctly. German scientists would need to recognize graphite as a viable reactor moderator, develop a functioning reactor early, and then build the industrial plants needed for uranium enrichment or plutonium production. That, in turn, would require diverting steel, electricity, and skilled labor away from conventional arms and other prestige projects like rockets.

Fourth, German industry would have to survive Allied bombing long enough to bring a device to completion. Secret facilities could be buried, dispersed, or located in occupied territory, but they would still face sabotage, intelligence leaks, and supply constraints.

Even with all of these changes, most technical analyses suggest that Germany would be lucky to field a small number of crude fission devices by late 1944 or 1945—roughly comparable in size and weight to the first American bombs.

First Use: London, Moscow, or the Front?

If the Nazis obtained one or two operational bombs first, the immediate question is where they would strike.

One school of thought is that London would be the prime target. The city had already endured heavy bombing and was the political heart of the Western Allied war effort in Europe. A single nuclear detonation over London might kill hundreds of thousands of people and wipe out central government districts in seconds. In Nazi thinking, that might be seen as a way to shock Britain into negotiation or to shatter Allied unity.

Another possibility is Moscow or a massed concentration of Soviet forces. By 1943–44, the Eastern Front had become the decisive theater. The Red Army was grinding forward, inflicting and suffering enormous casualties. A German leadership obsessed with defeating “Bolshevism” might choose to use its rare new weapon to annihilate a Soviet army group or devastate the Soviet capital, hoping to derail the offensive and regain some initiative.

A third, more tactical option would be battlefield use. Nuclear weapons could be employed against key railway junctions, port cities, or bridgeheads to slow Allied advances or destroy invasion forces, for example at a beachhead in France or a Soviet crossing over a major river.

In all of these scenarios, the first use is genocidal and terroristic. The regime that planned and executed the Holocaust is unlikely to exercise restraint once it possesses a weapon capable of destroying entire cities at once. Civilian casualties would be viewed as a feature, not a bug.

Would the Bomb Have Won the War for Hitler?

The central question is whether a small German nuclear arsenal could force an outright Nazi victory.

On one hand, the psychological impact of a nuclear strike in 1944–45 would be immense. No one would yet understand the full physics of radiation, but the immediate firestorm and blast would be unlike anything seen before. Allied publics, already exhausted by years of war, might react with panic and demands for peace. Governments would confront the possibility that more cities could be next.

On the other hand, the Allies had overwhelming industrial capacity, especially in the United States. Even if London or Moscow were destroyed, factories in North America, the Soviet hinterland, and the British Empire would still be producing tanks, aircraft, and ships at high volume. American leaders, insulated by geography, might decide to fight on even after a devastating strike on a European ally.

A limited number of German bombs also restricts options. If the Reich can only build a few devices per year, it cannot erase every enemy city. Once the weapon is revealed, Allied intelligence and bombardment would focus ferociously on suspected nuclear sites. German leaders would face a cruel arithmetic: use the few bombs quickly and hope to shock opponents into surrender, or hold them back and risk losing them on the ground.

The most plausible outcome is not a total Nazi victory but a brutal escalation. The Allies might consider retaliating with chemical weapons or with area bombing on an even larger scale. The United States would likely speed its own bomb program, armed with knowledge that the weapon was no longer theoretical. Once both sides had nuclear capability, a form of early Cold War could emerge in the closing stages of the conflict.

A Nazi-Led Nuclear Order

The darker branch of this alternate history is the one in which nuclear weapons, deployed early and ruthlessly, allow Nazi Germany to survive as a major power or even as the dominant power in Europe.

Imagine that a series of nuclear strikes forces a political settlement in the West—perhaps an armistice with Britain after London is destroyed—while the Soviet Union is pushed back but not fully conquered. The result could be a divided Europe in which a Nazi-controlled continental bloc, armed with nuclear weapons, faces a hostile but cautious Anglo-American world and a weakened Soviet state.

In such a scenario, the Holocaust and other mass crimes would likely be completed across much of Europe. Ethnic cleansing, forced resettlement, and the destruction of entire communities would be cemented behind a nuclear shield. Any thought of “liberating” occupied nations would be tempered by fear that Berlin could respond with nuclear attacks on London, New York, or other cities.

The global nuclear order would then grow out of this horror. Rather than being associated primarily with the end of the war against Japan and later superpower deterrence, nuclear weapons would be remembered first as tools of a genocidal regime. Arms control, if it emerged at all, would do so in a world where the original nuclear superpower was a dictatorship that glorified violence and racial hierarchy.

Technological development might also look different. A Nazi state committed to rearmament and racial empire would likely pour resources into delivery systems—missiles, long-range bombers, perhaps even early space projects—designed to project nuclear threat around the world. Education, media, and culture inside such a state would be saturated with propaganda about the “German bomb” as a symbol of destiny and dominance.

Nazi First Use, Allied Victory

There is another plausible path. Germany manages to build and use a small number of nuclear bombs but still loses the war.

Here, the Allies absorb catastrophic losses—perhaps the destruction of one or two major cities, or the annihilation of an invasion force—but decide that surrender to a regime already responsible for industrialized mass murder is unacceptable. American and Soviet advances continue, at terrible cost. Eventually, Allied forces capture or destroy German nuclear sites and secure key scientists.

In this branch, the postwar world is even more traumatized than in reality. The memory of cities erased by Nazi bombs would dominate politics for decades. War crimes trials would likely include charges related to nuclear atrocities. Survivors of nuclear attacks in Europe would join those of conventional firebombing and, later, any Japanese nuclear victims in shaping a powerful public taboo against the future use of such weapons.

The politics of reconstruction would also shift. A postwar settlement might be harsher toward Germany, with deeper territorial dismemberment or longer-term occupation justified by the nuclear threat. The association of atomic science with Nazi crimes could slow civilian nuclear power programs or push them onto a more constrained path.

Crucially, the moral story of the bomb would be different. Instead of being framed primarily as the weapon that ended the war against Japan and then as a deterrent between superpowers, it would be remembered first as a symbol of fascist brutality. Nuclear technology might be seen less as a necessary evil and more as an inherently tainted inheritance.

Why This Matters

Exploring this kind of counterfactual is not an exercise in fantasy for its own sake. It highlights how contingent the real history of nuclear weapons was—and how much depended on decisions inside scientific communities and authoritarian regimes.

In the actual timeline, a combination of scientific choices, resource priorities, and ideological factors meant that Nazi Germany never produced a bomb. The nuclear age instead began under the control of a state that, for all its own grave moral failings, did not rest on a doctrine of racial extermination in Europe. The early shape of arms control, deterrence, and non-proliferation grew out of that context.

Thinking about a world where the first nuclear blasts were ordered from Berlin forces a re-examination of several modern debates. It underscores why proliferation to unstable or openly genocidal regimes is feared so intensely. It highlights the role of scientists in pushing back when political leaders ask them to build weapons that threaten humanity itself. And it shows how international norms—like the taboo on nuclear use since 1945—might have evolved very differently if the weapon had entered history under a darker flag.

Counterfactuals also offer a warning against complacency. The real-world failure of the Nazi bomb program was not inevitable. It turned on miscalculations, fragmented management, and the chaos of a regime that prized ideology and short-term gain over consistent scientific strategy. Other authoritarian states may learn different lessons.

Real-World Impact

To grasp the stakes of this alternate history, it helps to trace its echoes into everyday life.

In one version of the twentieth century, large parts of Europe remain under nuclear-armed fascist rule for decades. Everyday experience there would be shaped by surveillance, indoctrination, and the constant background threat that any resistance might invite nuclear retaliation against neighboring states. Families would pass down stories not of liberation but of occupation entrenched by a weapon that made outside intervention almost unthinkable.

In another version, where the Nazis use the bomb but still fall, entire regions of Britain, the Soviet Union, or occupied Europe might grow up in the shadow of nuclear ruins. Urban landscapes could include permanent exclusion zones around the sites of wartime detonations. Memorial cultures would blend the names of extermination camps with those of cities wiped out in a single flash.

Even outside Europe, political arguments today would sound different. Debates over new nuclear states, missile defense, or arms reduction would invoke the example of Nazi first use as the ultimate cautionary tale. Diplomatic language about “rogue states” and “red lines” would sit under the long shadow of a regime that crossed every imaginable line once it held the most destructive weapon yet invented.

In schools and universities, discussions about scientific responsibility would also shift. The story of early nuclear physics would be told not only through the lens of Allied projects and their dilemmas, but through a parallel tale of what happens when a dictatorship seizes on cutting-edge science and channels it into total war.

Conclusion

The question of what might have happened if Nazi Germany had developed the nuclear bomb first is unsettling by design. It forces a confrontation with the idea of the world’s most destructive weapon in the hands of a regime already committed to mass murder and conquest.

Historically, the German program failed to reach that point because of scientific choices, resource limits, and the structural flaws of the Nazi state. The bomb instead emerged in a different political context and shaped a different set of postwar institutions, alliances, and norms. Those facts do not make the real nuclear age safe or simple, but they do mark a crucial divergence from some of the darkest possibilities.

Looking at this alternate path clarifies both contrasts and continuities. It shows how much worse the twentieth century could have been if a genocidal dictatorship had combined industrial killing with nuclear terror. At the same time, it reminds us that the basic dilemmas of nuclear weapons—deterrence, proliferation, moral responsibility—would still be with us in some form.

As debates continue today over new nuclear powers, treaty erosion, and the future of global security, this counterfactual serves as a warning and a prompt. It asks how close humanity has already come to disaster, and what kinds of political and scientific choices are needed to keep the worst branches of history’s “what ifs” from becoming reality.

These reflections are interpretive and speculative, offering a modern lens on historical ideas rather than asserting definitive claims