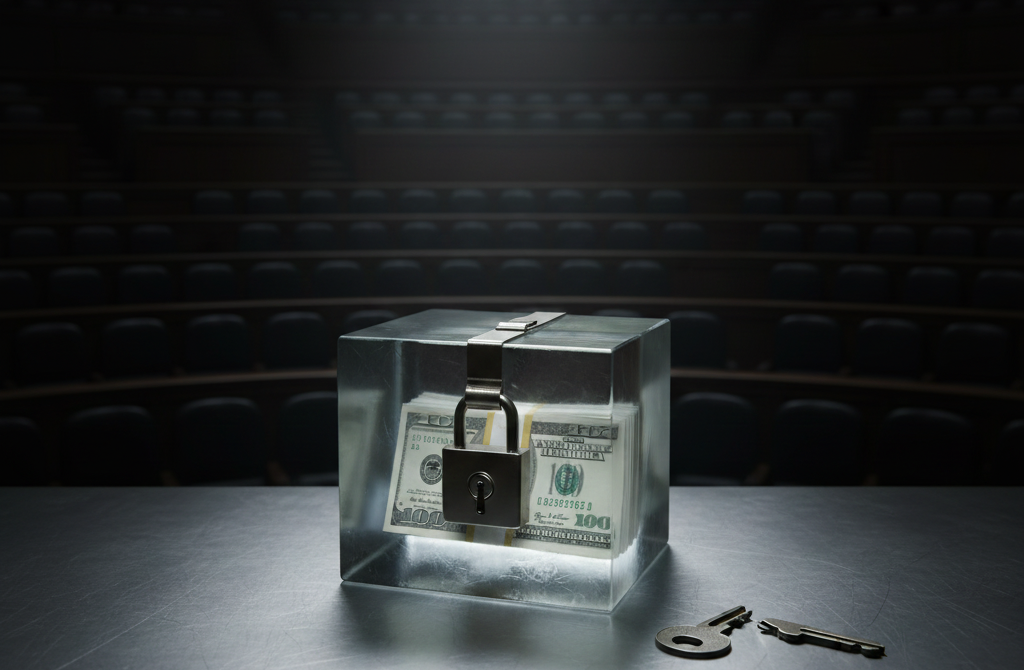

EU bans transfers of frozen Russian central bank assets, tightening the lock on €210 billion

The European Union has moved to stop any transfer of frozen Russian central bank assets back to Russia, a step designed to keep roughly €210 billion locked in place for as long as the war in Ukraine continues to shape Europe’s security and finances.

This matters because the money sits at the centre of a growing clash inside Europe: how to keep funding Ukraine, how to pressure Moscow, and how to do both without tearing holes in the EU’s own legal and financial foundations.

The immediate change is technical but powerful. It hardens the “immobilisation” of Russian state reserves held inside the EU and reduces the risk that a single member state could one day trigger their release by blocking the routine renewal of sanctions.

This piece explains what the EU actually did, why it did it now, what it unlocks for Ukraine’s financing, and what could still go wrong.

The story turns on whether Europe can keep Russian reserves frozen as leverage without undermining the trust that makes its financial system work.

Key Points

The EU has prohibited any direct or indirect transfer of immobilized Russian central bank assets back to Russia, including transfers involving entities acting on the central bank’s behalf.

The move aims to lock in roughly €210 billion in Russian sovereign assets held in Europe and reduce the risk of a future release through political blockage of sanctions renewals.

The decision is linked to plans under discussion to finance Ukraine in 2026–2027 using a large EU-backed loan structure tied to the frozen assets.

Several EU governments want stronger legal and financial protection against potential Russian lawsuits or retaliatory seizures linked to these assets.

Russia’s central bank has condemned the approach as unlawful and has pursued legal action against the main financial intermediary holding a large share of the immobilized reserves.

A key near-term milestone is a European Council meeting on December 18, where leaders are expected to revisit the financing plan and outstanding guarantees.

Background: EU bans transfers of frozen Russian central bank assets

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Western governments moved to block the Russian state’s access to parts of its foreign reserves held abroad. In the EU, this meant “immobilizing” Russian sovereign assets so they could not be moved, sold, or used in transactions that would effectively put cash back into Moscow’s hands.

Over time, one problem kept returning: many EU sanctions require periodic renewal, and renewals can be vulnerable to veto politics. Even if most member states want to maintain the freeze, the structure of decision-making can create moments where the legal basis for immobilization looks exposed.

The new prohibition targets that vulnerability by barring transfers back to Russia and by framing the measure as an urgent step to limit economic damage and security risks to the EU itself. It explicitly covers not only the Central Bank of Russia but also entities acting on its behalf or direction, including the Russian National Wealth Fund.

In practice, this is about more than symbolism. The bulk of the immobilized assets sit inside European financial plumbing, notably at a Brussels-based central securities depository, with the remainder held across other institutions. Keeping the assets locked is now tied to a broader financial strategy for sustaining Ukraine as the war drags on.

Analysis

Political and Geopolitical Dimensions

This is Europe tightening a screw that had started to look loose. The EU’s core objective is straightforward: deny Russia access to a war-chest, keep leverage for any eventual settlement, and preserve the credibility of Europe’s long-term support for Ukraine.

But the politics are not clean. Some governments argue that using emergency mechanisms and moving away from unanimity on such a sensitive question risks escalating internal EU tensions. Others see the shift as overdue, because the consequences of a single holdout are too large when the stakes include war funding and regional security.

There is also a messaging layer that matters internationally. Europe is signalling to partners and to Moscow that the immobilization is not a temporary inconvenience that can be waited out. At the same time, EU leaders are trying to avoid a step that many legal advisers consider more explosive: outright confiscation of the principal. The line between “keeping frozen” and “taking ownership” remains the political and legal tripwire.

Economic and Market Impact

The most immediate market impact is not about day-to-day prices. It is about legal risk, financial stability, and the perception of Europe as a safe place to hold sovereign reserves.

If the EU can lock assets indefinitely without triggering a wave of destabilising litigation, it strengthens the bloc’s ability to plan multi-year support for Ukraine. But if legal challenges multiply, or if Russia finds effective ways to retaliate against European financial institutions and their assets abroad, the costs could spread beyond this single case.

Belgium’s role illustrates the pressure point. When a large share of the immobilized assets sits in one jurisdiction and within one key financial intermediary, concentrated legal exposure becomes a policy problem for the whole bloc. That is why “guarantees” and burden-sharing have become as central to the debate as geopolitics.

A second-order effect is the precedent. Central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and global reserve managers watch how far sanctions go, and under what legal framing. Europe’s goal is to keep this action defensible as a protective measure linked to an ongoing war, rather than a casual rewriting of property rights. The more narrowly and consistently it can hold that line, the less likely it is to spook unrelated investors.

Technological and Security Implications

This story is often told as diplomacy and law. Underneath it is infrastructure: settlement systems, custodianship, and the mechanics of control over securities and cash.

Blocking “direct or indirect” transfers is not just a phrase. It is designed to cover workarounds, proxies, and complex transaction chains. The EU is effectively trying to ensure there is no technical path for assets to drift back to Russia through intermediaries, corporate vehicles, or rerouted reserve management.

There is also an explicit security argument: EU officials have linked the release of significant resources to heightened risks of hybrid activity and economic disruption. In that framing, preventing transfers is not only about Ukraine. It is about protecting the EU’s own economic resilience and security environment from escalation.

Social and Cultural Fallout

For many Europeans, the headline is moral: the aggressor should not get its money back while Ukraine absorbs the costs of destruction. For others, the worry is pragmatic: if the EU normalises extraordinary controls over sovereign assets, will that weaken long-term trust in European institutions?

In Ukraine, the focus is survival and continuity. Multi-year financing is not an abstract debate when it affects salaries, public services, ammunition, air defence, and the basic predictability of state budgets. Any step that makes support more durable has immediate human consequences.

In Russia, the narrative is predictably different: claims of illegality, sovereign immunity, and Western overreach. That framing is part of Moscow’s broader effort to deter further moves by threatening retaliation and legal escalation.

What Most Coverage Misses

The most overlooked piece is the incentive structure inside Europe. The biggest fights are not only “EU versus Russia.” They are about how risk is distributed among EU members and institutions.

When one country or one financial intermediary becomes the focal point for holding and administering immobilized reserves, it also becomes the focal point for lawsuits, countersuits, and political pressure. That creates a natural brake on bold policy, even among governments that want to go further.

The second missed point is time. This is not a single decision that “solves” the asset question. It is a move that buys durability. What Europe does next—whether it sticks to immobilization, expands the use of investment income, or shifts toward more aggressive legal theories—will determine whether the policy remains sustainable or becomes a destabilising legal and financial conflict.

Why This Matters

In the short term, the countries most affected are those directly financing Ukraine, those hosting key financial infrastructure, and those most exposed to retaliation or legal spillover. This also matters for industries tied to sovereign risk and cross-border settlement: banks, custodians, clearing and settlement firms, insurers, and any business that relies on predictable legal enforcement across jurisdictions.

In the longer term, the decision feeds into a global question: how far democratic states can go in weaponising financial infrastructure against aggressor states without damaging the system they depend on. Europe is trying to make the answer “far, but carefully.”

The next concrete events to watch are political and procedural. EU leaders are expected to revisit the wider Ukraine financing package and unresolved guarantees at the European Council meeting on December 18. Beyond that, attention will turn to whether legal actions intensify, whether Russia’s retaliatory options expand, and whether EU unity holds when the costs become more visible.

Real-World Impact

A budget official in Kyiv: Multi-year financing affects whether ministries can plan wages, procurement, and basic services without monthly panic. A more durable asset lock makes long-horizon support easier to design, even if the money is not directly spent tomorrow.

A compliance lead at a European bank in Frankfurt: “Direct or indirect transfer” rules can mean re-checking whole categories of transactions, counterparties, and custody chains. The policy becomes operational work, not just geopolitics.

A small manufacturer in northern Italy: If legal uncertainty escalates and financing costs rise for certain institutions, credit conditions can tighten at the margins. The chain from sanctions law to loan pricing is indirect, but it is real.

A risk manager at a Brussels-based financial services firm: Concentrated exposure to lawsuits and retaliation can change everything from insurance costs to capital planning. Even when the assets belong to Russia, the legal risks land on European balance sheets first.

Road Ahead

The EU’s ban on transfers of frozen Russian central bank assets is a strategic hardening of the financial front in the war, designed to stop political drift and prevent the accidental unfreezing of a vast pool of Russian reserves.

It sharpens Europe’s choices rather than removing them. Leaders can keep the assets immobilized as leverage, use associated financial flows more aggressively to support Ukraine, or explore legal pathways that edge toward confiscation. Each path carries trade-offs in law, risk, and financial credibility.

The clearest signs of where this goes next will come from whether EU governments can agree on credible guarantees for the jurisdictions most exposed, how courts respond to the first major legal tests, and what leaders decide on December 18 when the discussion shifts from freezing the money to putting it to work.