Should We Terraform Mars with Microbes?

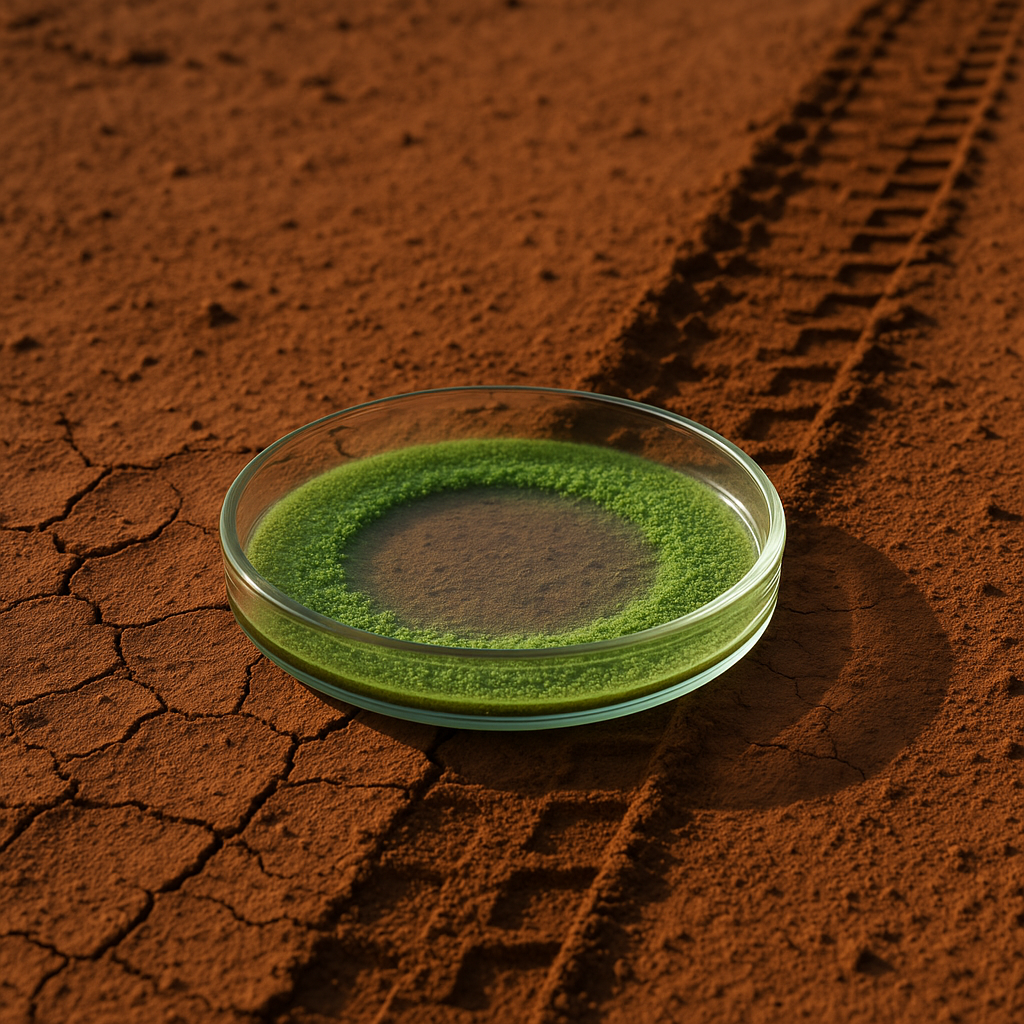

New experiments are showing that some microbes, lichens and even moss spores can endure space and Mars-like conditions far better than once thought. At the same time, new rover data keep hinting that Mars may once have hosted its own microbial life, and might still preserve traces of it below the surface. The debate over whether humanity should deliberately seed Mars with Earth microbes is no longer science fiction; it is quietly becoming a policy question.

This article looks at what scientists are actually discovering about hardy life forms, the rules that currently forbid deliberate contamination, and the ethical and strategic arguments on both sides. It explains how engineered microbes could one day help transform Mars, and why many researchers insist that any such step would be premature, or even reckless, while the question of indigenous Martian life remains open.

The story turns on whether humanity treats Mars as a laboratory to protect or a canvas to rework.

Key Points

Recent studies show that some microbes, lichens and plant spores can survive intense radiation, vacuum and Mars-like soil for extended periods, making biological terraforming more technically plausible than in past decades.

Current planetary protection rules, built on international space law, are designed to prevent “forward contamination” of Mars with Earth life and would need major revision before any deliberate seeding could occur.

Hints of possible ancient microbial activity in Martian rocks sharpen the ethical dilemma: seeding Mars could help humans settle there, but might erase the clearest evidence of whether life ever began independently on another world.

Synthetic biology and extremophile research are moving fast, and the same tools being developed for closed life-support systems could be repurposed to reshape Martian environments.

The choices made around the first sample-return missions and crewed landings will set precedents for every later step toward, or away from, terraforming.

Background

Terraforming is the idea of reshaping a planet’s environment to make it more Earth-like. For Mars, classic visions focus on thickening the atmosphere, warming the surface, and creating liquid water so that plants and eventually animals could survive in the open. In early concept studies, this often meant giant mirrors in orbit, greenhouse gases released into the air, or vast industrial machines churning out heat and chemicals.

Biology has now entered that picture. Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in conditions lethal to most life: bitter cold, high radiation, intense dryness, or toxic chemistry. Over the past two decades, experiments with bacteria, fungi, lichens and even small plants have shown that some can endure simulated Martian environments for days, months, or longer, especially when shielded in rock pores, dust, or ice. More recent work with moss spores outside the International Space Station and with lichens in harsh vacuum chambers suggests that a carefully chosen suite of organisms might survive, and even perform useful functions, on or beneath the Martian surface.

At the same time, Mars missions have grown ever more sensitive to signs of indigenous life. Rovers exploring ancient lakebeds have identified rocks whose chemistry and textures resemble those shaped by microbes on Earth. These are not proof of Martian biology, but they are strong enough “maybe” signals that scientists are pushing hard for sample-return missions, which would bring selected rocks back to Earth laboratories for definitive analysis.

To protect this scientific effort, and to avoid unknown risks to Earth, space agencies follow planetary protection rules rooted in the Outer Space Treaty and detailed by international scientific bodies. These rules seek to prevent Earth organisms from hitchhiking to places like Mars and colonizing them, and also to ensure that any material brought back from another world is handled with the highest level of biosafety. Deliberately releasing engineered microbes onto Mars would run directly against the current philosophy of these guidelines.

Analysis

Political and Geopolitical Dimensions

Any move toward terraforming Mars with microbes would unfold in a crowded political landscape. Major spacefaring nations, along with a small number of private companies, are racing to establish a durable presence on the planet. Each has its own priorities: scientific prestige, commercial opportunity, military signaling, or national narrative.

Planetary protection policy is currently framed as a global scientific norm rather than a tool of rivalry. Changing it to allow deliberate biological release would require difficult negotiations. Some states might argue that controlled microbial seeding is essential for affordable long-term human presence on Mars. Others might insist that the right to a pristine, or at least unspoiled, Mars is a shared heritage that no single country or company should be allowed to override.

Because space law is still relatively young, what happens around Mars would also shape norms for other worlds. If one actor unilaterally seeded microbes on Mars, rivals might respond by loosening their own restraints elsewhere, triggering a “terraforming race” in which planetary environments become bargaining chips in wider geopolitical contests.

Economic and Market Impact

Terraforming with microbes is often presented as a cost-saving measure. If engineered organisms could slowly release oxygen, fix nitrogen, build soil, or extract metals directly from Martian rock, future settlers might avoid shipping vast quantities of resources from Earth. Over decades, such biological systems could support agriculture, fuel production, and construction materials.

In the nearer term, however, the economics are less clear. Developing, testing and regulating bespoke microbial strains would demand serious investment in biotechnology, containment infrastructure, and long-duration experiments in Mars analog environments. Companies aiming to supply “living infrastructure” for space missions would face both technical uncertainty and regulatory risk, since their core product might be restricted or banned if planetary protection rules were tightened rather than relaxed.

Insurance and liability considerations also loom. If a microbe designed to stabilize Martian dust storms or extract water from brines behaved in unexpected ways, there could be long-run damage to scientific sites, habitats, or hardware. Assigning financial responsibility for such failures in an alien environment is an unresolved problem. Investors may be wary of backing ventures whose future depends on policy decisions that can swing with public opinion or isolated scientific findings.

Social and Cultural Fallout

For many people, Mars is more than a rock; it is a symbol. Some see it as a pristine desert that should be left as untouched as possible, a kind of cosmic national park. Others view it as humanity’s next frontier, a place where new societies could grow with fewer constraints than on Earth. Terraforming with microbes sits directly on the fault line between these visions.

If the public comes to believe that Mars once hosted its own life, even in simple microbial form, the idea of overwriting that record with a flood of Earth organisms may feel like vandalism. Arguments about “rights of nature” could extend beyond Earth, with philosophers and activists claiming that Martian ecosystems, even purely chemical ones, deserve moral consideration.

On the other hand, advocates of terraforming might frame microbial seeding as an extension of human stewardship, a way of expanding the domain of life in a barren universe. The story told to students, voters, and donors will strongly influence which side gains momentum. Cultural products—films, novels, games—are already shaping public imagination about Mars, and the imagery of either protecting or remaking the planet will color how any policy proposal is received.

Technological and Security Implications

Microbial terraforming assumes a high level of control over biology in extreme conditions. Synthetic biology tools can already rewrite genomes to create organisms that perform specific tasks, from emitting oxygen to producing biopolymers. For Mars, the challenge is to build strains that can work in low pressure, high radiation, and chemically harsh soils without routine human intervention.

Alongside the promise, there are significant security concerns. Techniques for designing organisms that endure on Mars are closely related to those that could make microbes more resilient on Earth. Knowledge developed for peaceful terraforming could be misused, intentionally or accidentally, in ways that complicate biosafety at home. Safeguards like genetic kill switches, dependencies on rare nutrients, or built-in expiration times might reduce but not entirely eliminate these risks.

There is also the issue of back contamination. If microbe-assisted terraforming proceeds in parallel with sample-return missions and human flights, the boundary between Martian and terrestrial biology becomes more porous. Distinguishing a native Martian microbe from an evolved descendant of an Earth strain becomes harder once both are present. This would not only be a scientific headache; in a worst-case scenario, it could complicate responses if a novel organism ever posed a health or ecological threat.

What Most Coverage Misses

Public debate often frames the question as a simple yes or no: should humanity terraform Mars with microbes or not? What is frequently overlooked is the importance of timing and sequencing.

One path would be “search-first, seed-later.” Under this approach, missions in the coming decades would focus on mapping possible habitats, drilling into ice and rock, and returning carefully selected samples to Earth. Only after an agreed threshold of evidence—either for or against existing Martian life—would any serious discussion of microbial release begin. Even then, initial trials might be tightly confined to controlled domes or underground reactors, not open landscapes.

Another underappreciated factor is the irreversible loss of information. The moment Earth microbes become widespread on Mars, future scientists will find it far harder to tell whether a given biomolecule, texture, or chemical pattern is indigenous or imported. That epistemic cost is difficult to quantify but immense: a unique opportunity to answer a fundamental question about life in the universe could be muddied for all time.

Finally, the debate around Mars quietly feeds back into Earth. The same biological engineering that might one day green Martian valleys is being explored for carbon capture, climate adaptation and ecosystem repair on this planet. Rules written in the name of “not contaminating Mars” could influence how bold societies are in using synthetic microbes to stabilize reefs, restore soils, or manage pollution. Decisions taken for a world 225 million kilometers away may reverberate in forests, farms and coastlines much closer to home.

Why This Matters

The people most immediately affected by this debate are those designing the next generation of Mars missions. Planetary protection standards will shape everything from how hardware is sterilized to where landers are allowed to touch down. Scientists planning sample-return campaigns must balance the desire to probe the most promising sites for life against the risk of disturbing them.

In the short term, the main consequence is a set of guardrails. No major space agency is proposing open-air microbial release on Mars today, but some researchers and commentators are arguing that the rules should evolve as biological and engineering capabilities grow. As budgets tighten and timelines for crewed missions slip or accelerate, pressure may mount to relax constraints that are seen as obstacles to settlement.

In the longer term, the stakes widen. If Mars is eventually treated as fair game for large-scale environmental engineering, that precedent will color human attitudes toward other celestial bodies, from icy moons with subsurface oceans to near-Earth asteroids. It will also signal how comfortable humanity has become with reshaping entire ecosystems, whether in space or at home.

Key developments to watch include funding and design decisions for Mars sample-return projects, formal reviews of planetary protection guidelines, and any move by national legislatures to update space activity regulation to address synthetic biology and off-world environmental modification.

Real-World Impact

A mission planner at a national space agency is drawing up designs for a crewed habitat on Mars. If strict planetary protection rules hold, the plan leans heavily on mechanical and chemical life-support systems that recycle air and water without releasing hardy microbes into the surrounding soil. If the rules soften, that same planner might be allowed to incorporate bioengineered organisms into walls, filters and waste-processing units that gradually extend into the local environment.

A small biotechnology company on Earth is pitching investors on “living infrastructure” for space. Its scientists are working on microbial consortia that can extract useful elements from Martian regolith and bind dust into stable surfaces. Venture capital interest rises and falls with each policy meeting and public statement from space agencies, because the company’s core business model depends on whether or not such microbes will ever be allowed to operate outside sealed reactors.

A planetary geologist has spent a career studying ancient lake deposits on Mars through rover images and lab analogs. For this scientist, the nightmare scenario is not that Mars will remain lifeless, but that unregulated microbial seeding will blur the line between Martian and terrestrial biosignatures. Their ability to answer the question “Did life ever arise independently here?” hinges on decisions made by policymakers and engineers who may never visit the sites in question.

A student activist, inspired by environmental movements on Earth, is building a campaign around the idea that Mars should be treated as a protected landscape. They argue that respect for non-Earth environments is a test of whether humanity has learned from its history of exploiting and degrading ecosystems at home. For them, the choice to seed or not to seed microbes on Mars is a moral statement, not just a technical one.

Road Ahead

The question of whether to terraform Mars with microbes is really a question about how far, how fast, and on what terms humanity should extend life into the wider solar system. On one side lies the promise of a slowly greening planet that can support long-term human presence thanks to invisible microbial workhorses. On the other lies the duty to preserve a rare natural laboratory that might hold the key to understanding life’s origins.

The fork in the road is not a single dramatic vote or launch, but a chain of smaller decisions: how strictly to enforce planetary protection, where to send the first sample-return missions, whether to prioritize closed habitats or open biological experiments, and how to weigh the interests of science, commerce and symbolism.

Signals that the story is turning will include any formal move to weaken or reinterpret contamination rules, the emergence of tested microbial systems designed specifically for Martian conditions, and, above all, the strength of evidence for or against indigenous life in Martian rocks and ice. Until those pieces fall into place, the wisest course may be to continue learning what Mars already holds before deciding what humans should add.