What caused COVID-19, ranked – and what still isn’t answered

COVID-19 reshaped the 21st century, but the basic question “What caused it?” still does not have a single, universally accepted answer. Almost five years after the first known cluster in Wuhan, scientific evidence and intelligence assessments still point in different directions, and crucial primary data remains out of reach.

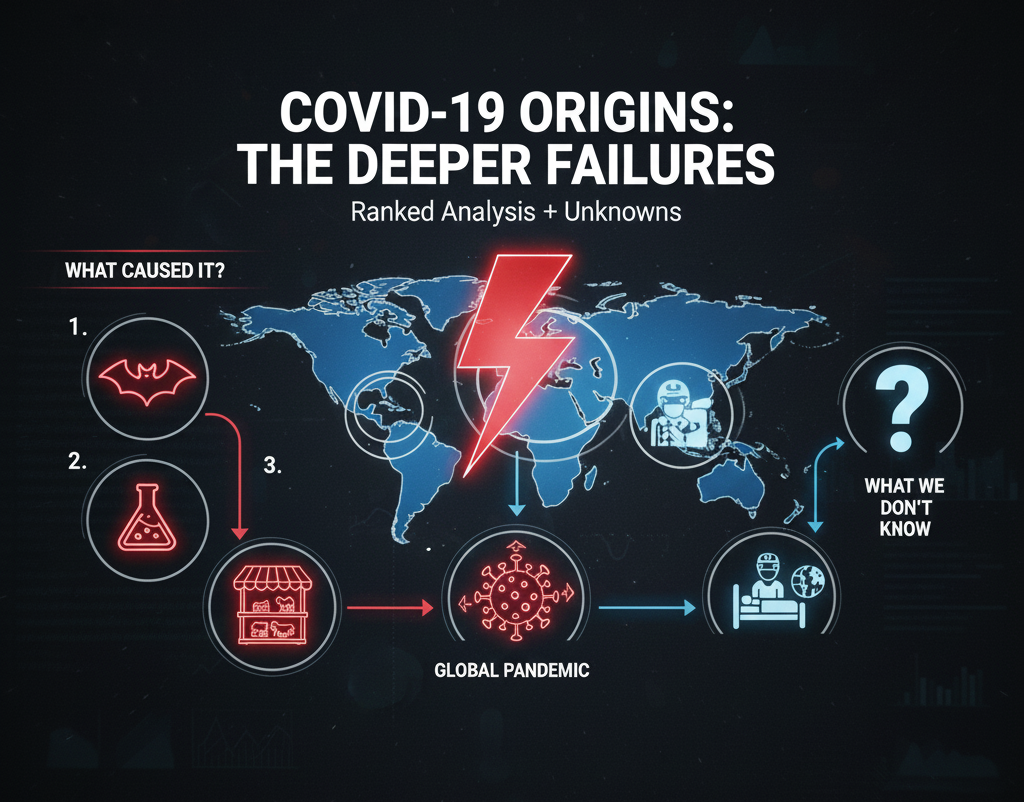

At the same time, there is a clear hierarchy of explanations for how the virus most likely emerged, and for why a local outbreak turned into a global catastrophe. Some causes now look solid. Others are still educated guesses. A few, once loudly debated, have been pushed to the margins by new data.

This piece ranks the leading explanations for how COVID-19 began, then ranks the deeper structural forces that turned SARS-CoV-2 into a worldwide pandemic. It also sets out the biggest unanswered questions — the gaps that still stop the world from saying with confidence how this started and how to prevent the next one.

The story turns on whether the world can agree on a plausible origin story in time to stop a repeat.

Key Points

Scientists still see natural spillover from animals as the leading explanation for how COVID-19 began, but it is not proven.

Several intelligence and government assessments now lean toward a possible laboratory-related incident, also with low confidence.

Both scenarios remain officially “on the table” because key early data from Wuhan markets, patients, and labs is still unavailable.

Beyond origin, deeper causes — global travel, delayed responses, fragile health systems, and information chaos — turned an outbreak into a pandemic.

Unanswered questions about the first human cases, intermediate animal hosts, lab records, and long COVID’s mechanisms leave big holes in the story.

Future pandemic risk hinges less on winning the origin argument and more on fixing the structural weaknesses that both main origin theories expose.

Background

COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2, a coronavirus that first came to international attention in late 2019, linked to a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. By March 2020, the outbreak had been declared a pandemic, and over the next years it led to millions of deaths, mass disruption, and a historic global vaccination campaign.

From the start, two broad explanations dominated:

Natural spillover. A virus circulating in bats, possibly through one or more intermediate animal species, crossed into humans. This is how previous coronavirus outbreaks like SARS and MERS began. Environmental sampling from the Huanan market later showed virus-positive surfaces near stalls that sold animals known to be susceptible, strengthening but not proving a wildlife link.

Laboratory-associated incident. A research-related accident in a lab working on coronaviruses — for example, infection of a worker during field sampling or lab work — allowed the virus to spread into the community. Several intelligence agencies have argued this is a plausible route, though without direct proof.

In June 2025, an expert advisory group convened by the World Health Organization restated that both main hypotheses remain plausible and that the origin question is still unresolved. The group called again for access to early patient data, supply-chain information for animals, and lab biosafety records, which have not been fully shared.

Alongside the origin debate, another set of questions emerged: why did this particular virus spread so explosively, and why did so many systems fail to contain it? Those broader causes are now much clearer than the exact spark.

Analysis

Ranked: leading explanations for how COVID-19 began

1. Natural animal-to-human spillover (most supported, still unproven).

Most virologists and evolutionary biologists still see a conventional zoonotic spillover as the top candidate. Coronaviruses very similar to SARS-CoV-2 circulate in bats, the virus’ genome shows no clear signs of deliberate engineering, and early human cases cluster around a market that sold multiple susceptible species. Surveys of scientific opinion in 2025 continue to show a strong majority favoring a natural origin, even as many acknowledge lingering uncertainty.

2. Laboratory-associated incident (plausible, politically charged, low-evidence).

Some intelligence services, and now one major government, argue that the most likely explanation is a research-related incident involving a coronavirus lab in Wuhan, though with “low confidence” because of missing records. Their case is circumstantial: proximity of labs to the outbreak, concerns about biosafety practices, and the lack so far of a confirmed intermediate animal host. Formal scientific bodies note that these points make a lab link possible but not proven, and stress that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence for wildlife routes.

3. Fringe theories (not supported by credible evidence).

Other ideas — such as a deliberately engineered bioweapon, or cold-chain frozen products as the primary route into China — have been examined and found to lack convincing evidence. Genetic analyses argue against deliberate manipulation, and cold-chain transmission is seen, at most, as a possible amplifying route, not a primary cause.

Ranked: deeper causes of the COVID-19 pandemic

If the origin is the spark, these are the main fuels that turned it into a global fire:

1. A virus with “perfect storm” biology.

SARS-CoV-2 spreads through the air, often from people without symptoms, with a relatively long incubation period and high viral loads early in infection. That biology made traditional containment tools — border checks, fever screening, symptom-based isolation — much less effective than against earlier outbreaks.

2. Global connectivity and late travel controls.

By the time attention focused on Wuhan, the virus had almost certainly already moved beyond China. Modern air travel meant that by January and February 2020, infected travelers were seeding outbreaks in multiple countries, often undetected.

3. Slow or fragmented early responses.

Many governments hesitated to declare emergencies, impose restrictions, scale up testing, or communicate clearly about airborne spread and masks. In several countries, this delay allowed exponential growth that later required harsher measures.

4. Health system weaknesses and inequality.

Hospitals in hard-hit areas lacked surge capacity, protective equipment, and staff. Long-standing health inequalities meant that poorer communities, minority groups, and frontline workers bore a disproportionate share of severe illness and death.

5. Information chaos and mistrust.

Mixed messaging on masks, changing guidance, and the rapid spread of rumors and conspiracies on social platforms eroded trust. That mistrust fed back into vaccine hesitancy and resistance to public health measures, prolonging the crisis.

Political and Geopolitical Dimensions

The COVID-19 origin debate now sits at the intersection of science and geopolitics. For one major international health body, the official line is that all main hypotheses remain open because China has not released enough early data or lab records to rule them in or out decisively.

Meanwhile, several intelligence agencies and legislatures in one major power have moved toward framing a lab-related origin as “most likely,” albeit with low confidence. That stance has fed diplomatic tensions, with Beijing rejecting lab-leak claims and, in turn, promoting its own narratives about potential foreign origins.

This clash affects more than pride. It shapes negotiations over lab inspections, biosecurity norms, funding for high-risk research, and the willingness of countries to share samples and data in the next emergency.

Economic and Market Impact

The question of what caused COVID-19 feeds directly into decisions about where to spend limited money for prevention.

If natural spillover stays the dominant explanation, governments are likely to focus on:

Cracking down on wildlife trade and risky markets.

Monitoring animal viruses at the human–animal interface.

Changing land use patterns that bring people, livestock, and wildlife into new contact.

If a lab incident is eventually judged more likely, pressure will intensify to:

Tighten biosafety rules.

Restrict or reshape gain-of-function studies that can make pathogens more transmissible or lethal.

Invest in safer lab designs and global oversight.

Either way, pharmaceutical and biotech industries face a future of closer scrutiny, and investors are watching how origin debates translate into regulation, intellectual property rules, and supply chain reshoring.

Social and Cultural Fallout

For the public, “what caused COVID-19” is not just a technical question. It carries moral weight. A natural-origin story highlights humanity’s relationship with wildlife, climate, and land use. A lab-incident story suggests human error inside scientific institutions, raising questions about trust, transparency, and accountability.

These narratives influence:

How people view scientists and public health authorities.

Willingness to accept future guidance or vaccination campaigns.

How societies process grief, blame, and responsibility for the pandemic’s toll.

If large groups feel that the true origin was covered up or politicized, that distrust may shape responses to entirely different crises in the future.

Technological and Security Implications

The unresolved origin amplifies concerns about “dual-use” research — scientific work that can advance medicine but also carries security risks.

Without a clear answer, security planners must assume both major pathways are credible:

That nature can still produce pandemic-grade viruses through routine animal–human contact.

That modern laboratories and fieldwork, even with safety protocols, can accidentally release dangerous pathogens.

This drives calls for global standards on lab safety, real-time reporting of lab accidents, and new tools to track how viral genomes and experiments move through research networks.

What Most Coverage Misses

Much of the public debate treats “lab vs market” as a binary choice. What often gets lost is that both leading explanations point to the same uncomfortable lesson: humans have created a world where high-consequence outbreaks are easier to start and harder to stop.

On one side, expanding cities, deforestation, industrial farming, and wildlife trade all increase the opportunities for viruses to jump from animals into people. On the other, a growing network of labs, field expeditions, and high-risk experiments means that even well-intentioned research can, in rare cases, carry spillover risk.

The deeper cause is not a single market or a single lab. It is a system that pushes up against natural and technological boundaries without yet building matching safety nets. That is the part of the origin question that matters most for the next decade.

Why This Matters

The origin of COVID-19 is not just an academic puzzle. It affects:

How countries design pandemic insurance, emergency stockpiles, and health system reforms.

Whether international law evolves to include lab inspections, wildlife trade bans, or both.

How young scientists choose their careers in virology, ecology, and biosecurity.

In the short term, the biggest consequences lie in diplomacy and regulation: upcoming global health meetings, national biosecurity strategies, and budget fights over lab funding and wildlife surveillance.

In the longer term, the unresolved origin feeds into bigger trends — rising geopolitical rivalry, debates over scientific openness, and the public’s willingness to trust institutions when the next crisis hits.

Events to watch include future reports from international advisory groups on origins, national reviews of high-risk research, and any new disclosures of early-case data or lab documentation from Wuhan or elsewhere.

Real-World Impact

A nurse in London who still treats patients with long COVID wants clarity not to assign blame, but to know whether the next threat is more likely to emerge from a distant forest or a research facility down the road — because that changes how hospitals prepare.

A wildlife trader in Southeast Asia faces new restrictions and inspections if natural spillover is treated as the dominant cause, reshaping livelihoods and pushing some trade into the shadows if not managed carefully.

A lab safety officer in a European virology institute is revising protocols, training, and reporting requirements under the assumption that a single mistake in the wrong place could have global consequences, whether or not that is what happened in Wuhan.

A finance official in a middle-income country must decide where limited funds go: strengthening surveillance in remote markets and farms, upgrading labs to higher safety levels, or building intensive care capacity. Their choices will be guided by which causes their government sees as most credible.

Conclusion

COVID-19 was not caused by a single decision or a single moment. It was the result of a new virus emerging — most likely through a familiar, natural route, though a lab incident remains possible — colliding with a world tightly wired together, slow to react, and full of structural weaknesses.

The core tension now is whether the world treats the origin question as a tool for prevention or as a battlefield for politics. The ranking of causes matters less as a scorecard and more as a guide for action: controlling risky human–animal contact, tightening lab safety, repairing health systems, and rebuilding trust.

The clearest early signs of which way this story is breaking will not come from a single “smoking gun” document. They will come from quieter shifts: real data-sharing on early cases, concrete reforms in wildlife trade and labs, and sustained investment in the unglamorous work of preparedness. Until then, the most honest answer to “what caused COVID-19?” is a layered one — part biology, part behavior, and part the systems humans built around both.