Oppenheimer Film Summary

Oppenheimer plot summary, themes, and ending explained

Full Story, Themes, and Ending Explained

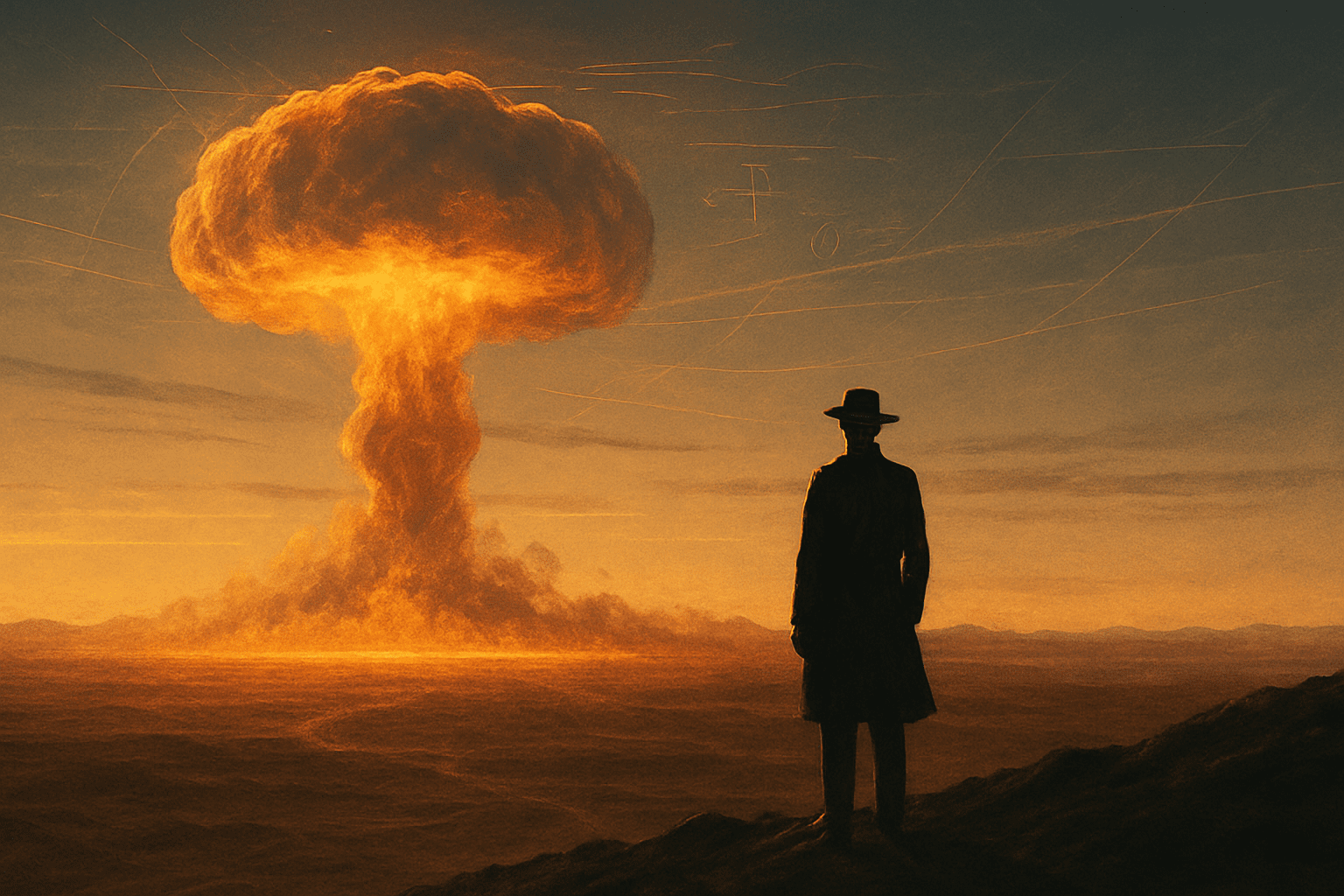

This Oppenheimer plot summary covers Christopher Nolan’s 2023 film Oppenheimer, a biography built like a political thriller. It tracks physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer from brilliant outsider to the public face of the atomic bomb, then to the target of a closed-door reckoning.

The film’s tension isn’t “Can the bomb be built?” It’s “What happens to the builder after the weapon changes the rules of power?” The story keeps returning to the same trap: scientific achievement creates political leverage, and political leverage demands someone to blame.

Nolan frames Oppenheimer’s life as two battles fought years apart. The first is the wartime race at Los Alamos to develop a new type of weapon. Secondly, a Cold War campaign is launched to deprive Oppenheimer of his influence by using his past as a weapon against him.

“The story turns on whether a man can live with the consequences of what he unleashes.”

Key Points

Oppenheimer is a character-driven biopic that plays like a courtroom and espionage drama.

The central arc moves from scientific ambition to moral injury, then to political punishment.

The Manhattan Project sections illustrate the intense logic of decision-making during wartime.

The postwar sections show how fear and bureaucracy can rewrite a person’s legacy.

The film uses intercut timelines to contrast Oppenheimer’s inner experience with the state’s “official” version of him.

Relationships—especially with Kitty Oppenheimer and Jean Tatlock—matter because the government treats them as evidence, not intimacy.

The story’s big question is not whether Oppenheimer feels guilt, but whether guilt changes anything once the system has the weapon.

The ending frames the bomb as the beginning of a chain reaction: escalation, paranoia, and a world permanently living under its own annihilation.

Quick Facts

Title: Oppenheimer

Author/Director: Christopher Nolan

Year: 2023

Format: Film

Genre: Epic biographical thriller drama

Primary setting: United States (Berkeley, Los Alamos, Washington, D.C.; mostly 1940s–1950s)

One-sentence premise (snippet-ready): A physicist leads the race to build the atomic bomb, then faces a Cold War reckoning that turns his own past into the case against him.

Names and Terms

J. Robert Oppenheimer — Theoretical physicist; scientific director at Los Alamos; both creator and scapegoat.

Kitty Oppenheimer — Oppenheimer’s wife; sharp, wounded, and fiercely protective when the state attacks him.

Jean Tatlock — Psychiatrist and lover; an intimate relationship recast as a security liability.

Gen. Leslie Groves — Military director of the Manhattan Project; chooses Oppenheimer for brilliance and risk tolerance.

Lewis Strauss — Atomic Energy Commission power player; a political rival with a long memory and sharper motives.

Edward Teller — Physicist; advocate for the hydrogen bomb; becomes pivotal in the hearing’s moral math.

Roger Robb — Lawyer and interrogator at the security hearing; turns biography into cross-examination.

Albert Einstein — Scientific elder and moral mirror; represents the long view and the dread underneath it.

Los Alamos — Secret lab city in New Mexico; where theory becomes hardware under wartime pressure.

Trinity Test — First atomic bomb test; the film’s hinge between triumph and irreversible consequence.

Full Plot

Spoilers start here.

The film is told in intercut timelines, but the core story is clear: Oppenheimer builds the bomb, then the state decides he is too complicated to trust. Here is the full plot summary with spoilers.

Act I: Setup and Inciting Incident

J. Robert Oppenheimer begins as a gifted, restless physicist who struggles with emotional control and social fit. In early academic life, the film shows him under intense pressure, prone to fixation, and capable of impulsive acts that hint at self-destruction. He is brilliant, but he is not steady.

He grows into a rising figure in American theoretical physics, drawn to the frontier questions that make older men defensive and young men hungry. He becomes a presence at Berkeley, teaching and building a network of colleagues who respect his mind even when they doubt his temperament. He is a synthesizer: someone who can connect people and ideas faster than most.

His personal life intertwines with politics. Oppenheimer moves through left-leaning circles at a time when anti-fascist activism and Communist Party affiliations overlap in messy, human ways. He falls into a relationship with Jean Tatlock, intense and emotionally complicated, and later marries Kitty, whose own past and blunt realism will matter when the state comes calling.

As the world tips deeper into war, the U.S. government fears Germany could build a nuclear weapon first. Gen. Leslie Groves arrives as the man who will turn a scientific possibility into a military program. Groves meets Oppenheimer, measures him quickly, and decides that the same traits that make him risky also make him ideal: speed, ambition, and an appetite for impossible problems.

Groves recruits Oppenheimer to help lead the Manhattan Project’s scientific effort. Oppenheimer accepts and begins shaping a secret city-lab at Los Alamos, pulling together competing minds and fragile alliances under a single deadline.

What changes here is that Oppenheimer stops being only a scientist and becomes a state instrument.

Act II: Escalation and Midpoint Shift

Los Alamos becomes a pressure chamber. Oppenheimer is tasked with creating a functioning weapon from theory while managing security rules, interpersonal rivalries, and the crushing reality that “success” will be measured in blast yield. He fights for the people he wants, the freedom he needs, and the urgency he believes the moment demands.

The film shows how the logic of war simplifies decision-making. There is fear of Nazi progress, fear of failure, and fear of being late. The lab’s culture becomes an engine: work, secrecy, competition, and the hardening belief that the moral debate can happen after the weapon exists. Oppenheimer pushes forward, but the film keeps inserting flashes of dread—visions of fire, shockwaves, and bodies—to show that he understands the horror even as he helps make it real.

Oppenheimer’s past follows him into the project. His connections to left-wing friends and groups, his relationship with Jean Tatlock, and the general atmosphere of ideological suspicion all become risks. He is questioned. He tries to navigate the demands of loyalty and secrecy while staying close to the people he loves, and that balancing act creates vulnerabilities.

Information and the Soviet Union become a crucial point of contention. Oppenheimer is approached through social networks that blur the line between political sympathy and espionage. He makes choices about what to report, what to conceal, and what story to tell authorities. Those choices are not just personal; they become future evidence.

The midpoint arrives with the Trinity Test. The device is assembled, the desert becomes a cathedral of wires and steel, and the team confronts the possibility that their calculations could be wrong in ways that end the world. The test succeeds. The blast is portrayed as both awe-inspiring and terrifying—an achievement that feels like a rupture in nature rather than a simple victory.

After Trinity, Oppenheimer becomes a public figure and a symbolic owner of the bomb, whether he wants that ownership or not. The war ends, but the meaning of the bomb does not. The film’s center of gravity shifts from building to governing, from physics to policy, from “can we” to “what now.”

What changes here is that the weapon’s success turns Oppenheimer from indispensable to politically dangerous.

Act III: Climax and Resolution

In the postwar period, Oppenheimer’s influence draws him into the machinery of national security. He enters advisory roles where decisions are abstracted into memos, committees, and budgets, even as the human cost remains overwhelming. He argues, debates, and cautions, especially as the Cold War intensifies and new weapons are proposed.

The hydrogen bomb becomes a defining political and moral battlefield. Oppenheimer is skeptical about the rush toward a weapon of even greater destructive power, and that skepticism is read by some as prudence and by others as disloyalty. In a climate of fear, motives are simplified: disagreement becomes suspicion.

Lewis Strauss rises as a powerful figure within the Atomic Energy Commission orbit. Strauss presents as respectable, rational, and patriotic, but the film reveals a deeper motive: resentment and rivalry. Oppenheimer’s public stature, his ability to humiliate a man with intellect and charm, and the policy clashes around nuclear strategy ferment into something personal. Strauss wants the story of American nuclear power to belong to administrators, not artists of theory who can question the whole enterprise.

The security clearance hearing becomes the arena where biography is turned into prosecution. Oppenheimer is subjected to interrogation led by Roger Robb, who treats relationships, friendships, and political associations as if they are contraband. The hearing process is private, but its consequences are public: to remove a man from influence without having to debate his ideas.

Witnesses appear, and the film makes the viewer feel the cruelty of institutional memory. Friends are forced into careful language. Enemies use precision. Kitty, fierce and furious, refuses the posture of shame. The hearing isn’t only about facts; it’s about tone, loyalty performance, and whether Oppenheimer can be made to look untrustworthy.

Edward Teller’s testimony becomes pivotal. He does not claim Oppenheimer is a traitor in the simple sense. Instead, he frames Oppenheimer as too complex, too hard to “understand,” implying that complexity itself is a national security problem. The film treats this as a moral turning point: a colleague translating intellectual disagreement into bureaucratic condemnation.

The hearing ends with Oppenheimer’s clearance revoked, effectively stripping him of formal power. The punishment is surgical: he remains famous, but he is isolated from the machinery that decides the future of nuclear weapons. The state does not need to imprison him. It only needs to revoke his access and stain his credibility.

Intercut with this is Strauss’s own political battle: his Senate confirmation hearing. Strauss expects advancement, but opposition forms, and a key reversal occurs when the role Strauss played in Oppenheimer’s downfall becomes clearer. Testimony and political maneuvering turn the tables. Strauss’s nomination fails, and the film frames it as a delayed consequence—an institutional rebuke that arrives too late to undo the damage.

In the final movement, Oppenheimer returns to Albert Einstein in a scene that functions like a confession and a verdict. Earlier, they had discussed the fear that the bomb could ignite a catastrophic chain reaction. Now the dread is no longer about literal ignition in the atmosphere. It is about geopolitical ignition: the arms race, escalation, and an end-state where human survival depends on restraint that history rarely supplies.

Oppenheimer tells Einstein, “I believe we did,” and the film closes on visions of global nuclear fire. The ending lands on a bleak emotional note: triumph has already curdled into inevitability, and the man who helped start the chain reaction cannot stop it.

Analysis and Themes

Theme 1: Genius as a National Resource

Claim: The film argues that the state will praise genius only while it is useful, then control it when it becomes inconvenient.

Evidence: Groves recruits Oppenheimer because he can do what others cannot, tolerating his flaws during wartime. Later, the same traits—intensity, politics, moral questioning—are reclassified as risk during the hearing. Oppenheimer’s value is situational, not personal.

What does this mean? Modern institutions continue to view talent as a tool, not as an individual. When a thinker questions the direction of the system, the system often interprets this challenge as instability, disloyalty, or a lack of teamwork.

Theme 2: The Moral Injury of “Necessary” Work

Claim: The film presents guilt not as a private emotion but as an injury created by rationalized violence.

Evidence: The Trinity success is followed by dread, not release. Oppenheimer’s postwar scenes show him haunted by what the achievement implies, even as committees talk in clean language about strategy. The film refuses to let “we had to” erase the human cost.

So what: Many modern jobs produce distance between action and consequence—algorithms, finance, surveillance, drones, and disinformation. The film asks what happens when the mind can’t maintain that distance anymore.

Theme 3: Security as a Story, Not a Fact

Claim: The hearing shows “security” operating as narrative control more than objective truth-seeking.

Evidence: Robb’s questioning treats personal relationships as incriminating by definition. Oppenheimer’s past is reassembled into a coherent story of risk, even when individual events are ambiguous. The process is designed to reach a conclusion that will satisfy institutional anxiety.

So what? In any era of fear, institutions prefer simple stories: hero, traitor, threat. Complexity feels like danger because it prevents clean action. That is how procedural systems can become moral machines.

Theme 4: Power Punishes Humiliation

Claim: Strauss’s arc suggests that policy disagreements often become personal vendettas disguised as principle.

Evidence: Strauss’s resentment grows from moments where he feels publicly diminished and intellectually outplayed. The film links his pursuit of Oppenheimer’s downfall to status injury as much as ideology. His confirmation collapse mirrors the same political logic he used on Oppenheimer.

So what: In workplaces and politics, humiliation can be more motivating than money. People do not always seek truth; they seek restoration of rank. Systems that reward ego can turn governance into revenge.

Theme 5: The Myth of Control

Claim: The film insists that creating a world-changing tool means surrendering control over how it will be used.

Evidence: Oppenheimer helps build the bomb to win a war, but the weapon outlives that purpose immediately. Postwar debates show that restraint is fragile and escalation is tempting. The final images make the chain reaction psychological and geopolitical, not only physical.

So what: This is the core warning for modern technology. Once a capability exists—nuclear, biological, or digital—someone will operationalize it. Inventors rarely get veto power after invention.

Theme 6: Private Life as State Evidence

Claim: The film portrays intimacy as a liability once the state decides it needs leverage.

Evidence: Jean Tatlock becomes more than a lover; she becomes a dossier item. Kitty becomes more than a spouse; she becomes a witness under pressure. The hearing reframes human messiness as incrimination.

So what: In highly regulated or politicized environments, your relationships, messages, and past associations can be reinterpreted later under a new lens. The film captures the dread of living in a world where context can be stripped away on demand.

Character Arcs

Protagonist: At the start, Oppenheimer believes intellect and contribution will earn him durable authority. By the end, he understands that authority is conditional and can be revoked by politics, not disproved by facts. The forcing moments are Groves’s recruitment (power offered), Trinity (power unleashed), and the hearing (power withdrawn).

Secondary arc: Kitty shifts from trying to survive Oppenheimer’s orbit to becoming his defender, refusing the ritual of shame. Strauss shifts from respected administrator to exposed operator, learning that the same machinery he used can turn on him.

Craft and Structure: What Makes It Work?

The film’s structure is the point. Nolan avoids depicting a linear progression, as Oppenheimer's life did not unfold in this manner. The intercut timelines make the viewer feel the trap: even in moments of triumph, the future punishment is already waiting. That creates a constant undertow of dread.

Color and black-and-white sequences create a psychological split between lived experience and institutional record. The film treats memory as subjective and bureaucracy as performatively objective, even when bureaucracy is driven by politics.

The dialogue is dense but purposeful. Characters speak like people who understand that language is power: a sentence can become a policy; a phrase can become a verdict. The film’s tension often comes from who gets to define what happened.

What Most Summaries Miss

Most summaries treat the security hearing as a “trial” and Teller’s testimony as a simple betrayal. The film is more uncomfortable than that. It shows how a system can make decent people participate in harm while telling themselves they are protecting something bigger.

The real twist is not that Oppenheimer had political associations. It’s that the state doesn’t need a crime to remove you from influence. It needs doubt, procedure, and the right story. The hearing is less about discovering truth than about deciding what kind of person is allowed near power.

The Einstein scenes underline this. The film isn’t only about one man’s guilt. It’s about the moment the world enters an era where decisions are made under the shadow of total destruction, and “winning” becomes indistinguishable from surviving the aftermath.

Relevance Today

Technology races: AI, cyber tools, and biotechnology move faster than governance. Like Los Alamos, the pressure is “if we don’t build it, someone else will,” and that logic short-circuits ethics.

Reputation as a battleground: Institutions still use processes to settle power struggles—investigations, hearings, and compliance reviews—where the outcome can be shaped by framing.

Information as leverage: Personal history is searchable and permanent. The film’s fear of dossiers feels contemporary in a world of data breaches, surveillance, and reputational warfare.

Polarized politics: Ideological suspicion turns disagreement into treason quickly. The hearing reflects how fear can make nuance look like danger.

Workplace dynamics: Strauss’s resentment mirrors modern status politics: people weaponize policy language to punish humiliation, not to enforce principle.

Media and narrative control: The fight over who “owns” the story—scientists, politicians, or institutions—echoes today’s battles over misinformation, trust, and public legitimacy.

Nuclear risk remains: The film’s closing dread still maps onto real-world nuclear postures, escalation dynamics, and the uneasy reliance on deterrence to prevent catastrophe.

Ending Explained (Plain Language)

The ending is not a puzzle about what Einstein “really said.” It’s a moral verdict delivered in quiet language. Oppenheimer is remembering an earlier fear: that the bomb might set off a chain reaction that ends everything. In the end, he realizes the chain reaction did happen—just not as a literal atmospheric ignition.

The ending means the Trinity Test started an irreversible political and psychological process: the arms race, the doctrine of deterrence, and a world where annihilation becomes an accepted background condition.

The final images of nuclear destruction aren’t prophecy in the strict sense. They are the visual form of Oppenheimer’s understanding that the weapon changed what nations can demand, what leaders can threaten, and what citizens have to live with.

Why It Endures

Oppenheimer endures because it refuses the comfort of a clean moral label. It doesn’t let Oppenheimer be only a hero, and it doesn’t let his enemies be only monsters. It shows a world where ambition, fear, vanity, and genuine patriotism can all coexist in the same room—and still produce catastrophe.

This film is for viewers who like history as a living argument, not a museum display. It is also for anyone interested in how institutions convert uncertainty into punishment. People who want a straightforward war narrative or a simple villain may find it cold, because the real antagonist is a system that rewards creation and fears conscience.

The final impression is brutal and simple: once you build the thing that changes the rules, the rules will change you back.

More insight, less noise—subscribe and explore the full range at Taylortailored.co.uk