Saving Private Ryan, Summary

Saving Private Ryan Summary: Plot, Themes, Ending Explained

A Full Plot Breakdown, Themes, and Ending Meaning

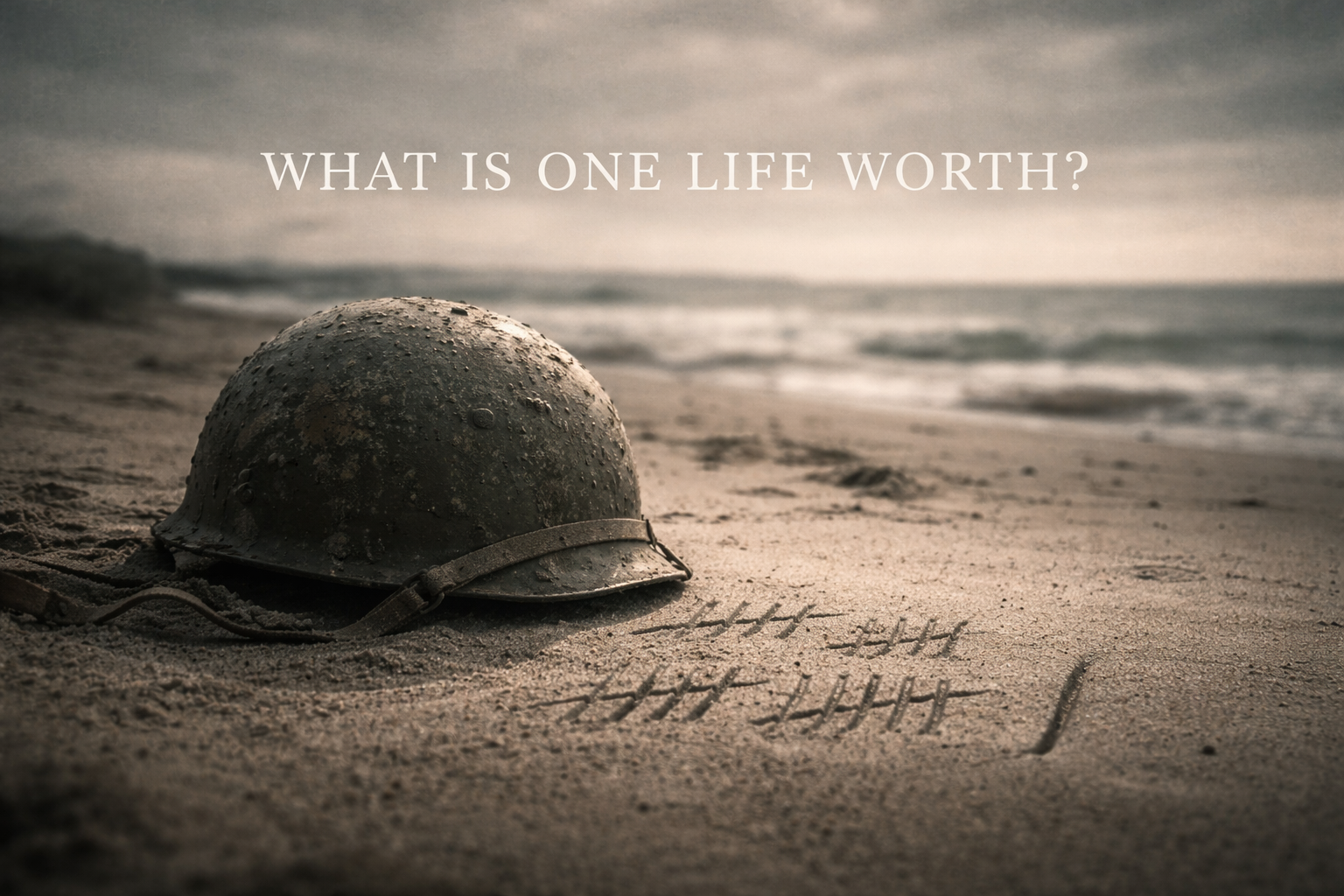

Saving Private Ryan (directed by Steven Spielberg, 1998) is a war film built around a simple order that becomes morally complicated the second it meets reality. A small U.S. Army squad is sent behind the front lines to locate one missing paratrooper and bring him home. The mission sounds humane. The mission also seems insane to the soldiers who are being asked to risk their lives to complete it.

This Saving Private Ryan summary is built to do two things at once: tell the story with clear cause-and-effect and explain why the story still hits so hard decades later. The film is not only about combat. It is about leadership under impossible constraints, the way institutions turn people into numbers, and the private burden carried by the one person who survives a choice everyone else paid for.

The central tension is blunt. War treats lives like inventory. The mission demands the opposite: treat one life as priceless without erasing the value of the lives used to protect it.

“The story turns on whether one man can be saved without reducing everyone else to expendable collateral.”

Key Points—Saving Private Ryan summary

A U.S. squad is ordered to find Private James Francis Ryan and send him home after his brothers are reported killed.

Captain John Miller leads the mission, but the order quickly becomes a test of authority, fairness, and morale.

The squad’s losses make the mission feel less like mercy and more like a bargain written in other men’s blood.

A captured German soldier becomes a moral flashpoint that exposes the squad’s rage and their need for rules.

The search ends when the squad finds Ryan, but the “rescue” is not a simple extraction.

The mission transforms into a last-stand defense of a strategic bridge, where sacrifice becomes unavoidable.

The ending frames survival as a lifelong debt, not a happy outcome.

Quick Facts

Title: Saving Private Ryan

Author/Director: Steven Spielberg

Year: 1998

Format: Film

Genre: War drama

Primary setting: Normandy and rural France in 1944, framed by a later visit to an American military cemetery

One-sentence premise (snippet-ready): A battle-hardened captain leads a small squad into occupied France to find a missing paratrooper and bring him home, only to discover the mission’s “mercy” demands a brutal price.

Names and Terms

Captain John Miller—the squad leader; calm under pressure, privately exhausted by responsibility.

Sergeant Mike Horvath—Miller’s closest ally; steady, loyal, and practical.

Private James Francis Ryan—the missing paratrooper; the mission’s target, but not a passive prize.

Corporal Timothy Upham—a translator added to the squad; decent intentions, little combat experience.

Private Richard Reiben—blunt, skeptical, and openly resentful of the mission’s logic.

Private Adrian Caparzo—tough and compassionate; his death sets the tone for what the mission costs.

Medic Irwin Wade—the squad’s medic; his loss detonates the men’s anger and moral drift.

Private Daniel Jackson — the sniper; composed, lethal, and spiritually anchored.

Private Stan Mellish—aggressive and outspoken; his fate becomes the film’s most painful moral test.

Ramelle Bridge—the strategic bridge Ryan’s unit is defending; the mission’s final battleground.

Full Plot

Here is the full plot summary with spoilers.

The film begins in a quiet place that feels like an answer to a question you have not heard yet: an American military cemetery in France. Rows of white crosses stretch into the distance. An elderly man walks with his family, searching for a specific grave as if the stone can verify something he has been trying to prove to himself for decades. When he finds it, he breaks down. The film then cuts into memory, and the calm dissolves into violence.

Act I: Setup and Inciting Incident

June 6, 1944. Omaha Beach. The landing is not presented as a heroic pageant. It is shown as a machine designed to shred human bodies. Landing craft doors drop. Men run into shallow water and fall before they can find footing. Some drown under the weight of their gear. Others are cut down by machine gun fire that seems to come from the air itself.

Captain John Miller leads a group of Rangers through the chaos. He is introduced through action rather than biography. He signals, shouts orders, drags men to cover, and keeps moving because stopping is the same as dying. Even the camera seems overwhelmed, as if the film is trying to show how war feels before it explains what war means.

After the beach is secured, the story shifts to a different kind of brutality: notification telegrams. The U.S. Army learns that three brothers from the Ryan family have been killed in action. Their mother is about to receive the sort of news that empties a home in one afternoon. A fourth brother, Private James Francis Ryan, is listed as missing after the airborne drops. The U.S. command decides she will not lose all her sons. Orders are issued to find Ryan and send him home.

Miller is assigned the mission. He assembles a squad: Sergeant Mike Horvath, Private Richard Reiben, Private Adrian Caparzo, Private Daniel Jackson, Private Stan Mellish, medic Irwin Wade, and Corporal Timothy Upham, a translator pulled into the unit because he can speak German and French. The addition is telling. This is not a clean combat team. It is a small improvised knife pushed into an enormous war.

The squad moves inland through wrecked towns and uncertain roads. They stop in a ruined village where civilians are trapped in fear and confusion. Caparzo, a hard-looking soldier with a trace of tenderness, tries to help a frightened French girl. It is a moment of ordinary humanity in an inhuman setting. A German sniper kills him for it. The squad kills the sniper, but the damage is already done. The mission has a body count, and it is not even close to finished.

“What changes here is that the mission stops feeling like a bureaucratic errand and starts feeling like a trade paid for with real men.”

Act II: Escalation and Midpoint Shift

With Caparzo dead, the squad’s friction sharpens. The men are not only tired and afraid; they are angry at the logic of what they are doing. Reiben voices the question others are swallowing: how does it make sense to risk eight lives to save one? Miller maintains discipline, but he cannot offer a satisfying moral equation. He can only offer duty, and duty is an answer that gets thinner the more blood it costs.

They find a soldier named James Ryan, only to realize he is the wrong one. The mistake hits hard because the squad has been dragging itself forward on the hope that the mission ends the moment they locate the name. Instead, they are forced to deliver terrible news to a stranger: the Ryan brothers are dead, and the war is still chewing through families. The wrong Ryan becomes a mirror of the right one. One man can be pulled from the machine, but the machine does not stop.

The squad rests in a church. The stillness reveals small truths. Miller’s hand trembles, a sign of stress he tries to hide. The men talk, joke, and bicker, circling the grief because naming it directly would make it heavier. This pause matters because it shows the squad as people, not symbols. They are not made of bravery. They are made of habits that keep panic from winning.

They get a lead that the correct Ryan may be near Ramelle. On the way, they come across a German machine-gun nest. Miller decides to take it out. The men resist because it is not their mission. Miller insists anyway. His decision exposes his belief that leadership is not only following orders but also making moral choices in the moment you have the power to prevent future deaths.

The assault is successful, but the victory is poisoned. Medic Irwin Wade is mortally wounded. Wade’s death is slow, intimate, and terrible because it is not cinematic. There is no clean last line, only pleading and fear. The squad watches the man who saves others fail to save himself. This does not inspire them. It breaks something inside them.

In the aftermath, they capture a German soldier who surrenders. The squad wants to execute him. It is not tactical. It is emotional. They want a life to balance Wade’s life. Upham argues for mercy, insisting that killing a surrendering prisoner makes them no better than the enemy. Miller chooses a compromise: he spares the prisoner and orders him to surrender to the next Allied unit. The men nickname the prisoner “Steamboat Willie,” turning him into a joke because it is easier than admitting the moment has changed them.

The squad’s cohesion fractures. Reiben threatens to leave. Miller pulls them back from the edge by revealing the truth he has kept private: he was a schoolteacher before the war. The confession matters because it is not a sentimental detail. It is a reminder that the squad leader is a person who did not belong to violence until violence drafted him. It also shows Miller using vulnerability as command. He earns obedience by sharing what the war has taken from him.

They reach Ramelle and find Private James Francis Ryan alive. Ryan is embedded with paratroopers defending a bridge that matters strategically. Miller explains the order. Ryan refuses to abandon his post. He will not leave the men who have fought beside him. He argues that he does not deserve to go home more than they do. The squad is furious. They have lost men to reach him. Now the man they came to save will not be saved.

Miller makes the defining choice of the story: he stays. He agrees to help defend the bridge, even though it was not the original mission. The squad shifts from searching to holding. The mission becomes something larger than one life, and that is both a relief and an even heavier burden.

“What changes here is that the story pivots from retrieval to sacrifice, and the squad’s purpose becomes the bridge rather than the order.”

Act III: Climax and Resolution

Miller takes command of the defense. The paratroopers are outgunned and expecting armor. Miller turns the town into an improvised trap. Streets become chokepoints. Buildings become cover. Explosives are placed where they can cripple tanks. The preparation is methodical, almost calm, because panic would waste what little time they have.

The German assault arrives with infantry and tanks. The defense is not a single heroic moment. It is a series of choices that each cost something: hold this corner, retreat to that street, sacrifice one position so another can survive. Jackson, the sniper, kills with eerie composure from a high vantage point, as if belief has given him distance from fear. Horvath fights like a stabilizing force, keeping the group intact as bodies fall and the town collapses into smoke.

Upham’s thread becomes unbearable. He carries ammunition, tries to help, and wants to be useful, but he is overwhelmed. He is a man built for language and rules now trapped inside a world where morality is decided at the speed of a trigger pull. At a crucial moment, he freezes near a staircase while fighting rages nearby. He hears a struggle that demands action. He cannot move.

Mellish is caught in close combat with a German soldier. The fight becomes intimate and horrifying because it is quiet enough to hear breath and fear. Mellish is stabbed. Upham remains frozen, listening. The film forces the viewer to sit with the idea that good intentions do not matter if you cannot act when it counts. Upham’s failure is not treated as comedy or simple cowardice. It is treated as a human collapse under unbearable pressure.

The defense collapses toward the bridge. Men die. Miller is wounded. Reiben keeps fighting because there is nowhere else to go and nothing else left to defend except each other. Then, at the moment the defense seems doomed, U.S. reinforcements arrive and turn the tide. The Germans are pushed back. The bridge is held.

But the victory does not feel like triumph. It feels like survival with a bill attached.

Miller, mortally wounded, pulls Ryan close. He tells him to “earn it.” The line lands as a command and a plea. It is Miller trying to shape meaning out of an exchange that would otherwise be unthinkable: several men died so one man could go home. If Ryan treats his survival as random luck, the sacrifice becomes a cruel accident. If Ryan lives a good life, the sacrifice becomes a foundation instead of a void.

The film returns to the cemetery. The elderly man is revealed as Ryan. He stands over Miller’s grave and asks his wife to tell him he has been a good man. The request is not romantic. It is moral. He needs confirmation that his life has balanced the dead, even though it cannot.

The story ends on graves and flags and a question that has no clean answer: can any life truly “earn” what was paid for it?

Analysis and Themes

Theme 1: The arithmetic of sacrifice

Claim: The film argues that war turns morality into math, but the math never comes out clean.

Evidence: The mission begins as a mercy order meant to spare a mother, yet it immediately costs Caparzo’s life in a civilian moment. Wade’s death occurs because Miller chooses to attack a gun nest that is not part of the mission, widening the circle of sacrifice. The final defense at Ramelle adds more bodies to the ledger to hold a bridge and preserve one man’s chance to live.

So what: The film refuses the comforting lie that sacrifice automatically equals meaning. It shows how institutions try to make loss feel justified by attaching it to a story, a mission, or a symbol. In modern life, people still do this with work, family, and politics: they endure harm and call it purpose. The film asks a sharper question: what if the label “worth it” is something we invent so grief does not destroy us?

Theme 2: Leadership under impossible choices

Claim: The film frames leadership as choosing between wrong options without collapsing into self-pity or cruelty.

Evidence: Miller leads through the Omaha Beach slaughter by making quick decisions that save some men and doom others. He chooses to attack the machine-gun nest to prevent future deaths, even when his squad sees it as mission drift. He chooses mercy with the prisoner to preserve a boundary, even when it breaks squad trust. He chooses to stay in Ramelle, accepting a fight he did not ask for because leaving would betray something deeper than orders.

So what? Most leadership in the real world is not heroic. It is sustained decision-making under imperfect information. People want leaders who can give clean reasons and clean outcomes. The film shows that in high-stakes systems, you often get neither. The best you can do is make choices that align with a core value, then carry the cost without pretending it was painless.

Theme 3: The fragility of moral rules

Claim: The story tests whether rules are real values or luxury items that vanish under pain.

Evidence: The squad’s impulse to execute the surrendered prisoner spikes after Wade dies, showing how grief turns into permission. Upham argues for rules, not because rules feel comforting, but because rules are the only fence keeping them from becoming predators. Miller tries to preserve that fence, yet the squad experiences the decision as betrayal because the war has trained them to treat mercy as weakness.

So what: In modern societies, people often claim principles until fear or humiliation arrives. Then “exceptions” multiply. The film dramatizes that slide in a way that feels personal rather than abstract. It suggests that ethics are most real when they cost you something, because free morality is not morality at all. It is just self-image.

Theme 4: The burden of the survivor

Claim: The film treats survival as a responsibility that can become a lifelong psychological sentence.

Evidence: Miller’s “earn it” becomes the final instruction Ryan carries out of the war. The cemetery framing reveals an old man still seeking moral approval, as if a good life can retroactively justify the dead. Ryan’s need to ask his wife if he is a good man shows survival as doubt, not relief.

So what? Survivor guilt is not limited to war. People carry it after accidents, layoffs, illness, and family collapse. The film captures the quiet version: the feeling that your life must become evidence, that you must live in a way that proves you deserved the luck you received. That mindset can drive meaning, but it can also erase joy and replace it with perpetual moral accounting.

Theme 5: What “saving” really means

Claim: The film argues that saving a person is never only physical; it is also about identity and belonging.

Evidence: The mission is officially about extracting Ryan, but Ryan refuses because leaving would separate him from the men who shaped his survival. Miller’s squad begins as a unit defined by orders, but becomes a unit defined by chosen obligation, culminating in defending the bridge together. The cemetery shows that Ryan was “saved,” but not freed; he carries the mission inside him forever.

So what? Modern life uses the language of rescue all the time: saving someone from poverty, saving someone from addiction, saving someone from failure. The film warns that “saving” can become another kind of control if it ignores the person’s own sense of duty and identity. It also suggests that community is not a soft value. In crisis, belonging can matter more than safety.

Character Arcs

Protagonist (Captain John Miller): At the start, Miller’s belief is that duty is executed through competence: do the job, keep moving, protect your men, survive. By the end, his belief becomes sharper and heavier: duty also means choosing what is decent when the mission’s logic collapses. Key moments include his decision to attack the gun nest, his choice to spare the prisoner, and his decision to stay at Ramelle. His final request to Ryan is not about victory. It is about turning chaos into a moral story someone can live with.

Private James Francis Ryan: Ryan begins as a missing name, then becomes a man defined by loyalty to his unit. He refuses rescue because he believes leaving would be an insult to those who fought beside him. By the end, he becomes the living container for everyone else’s sacrifice. His arc is not about becoming braver. It is about becoming the person who carries the cost forward, for better and worse.

Corporal Timothy Upham: Upham begins as a principled outsider who believes rules can keep men human. Under pressure, he becomes paralyzed, and his failure produces a private moral wound. His arc is about the gap between values and action. The film uses him to show that being “good” in theory is not the same as being good when fear takes over your body.

Craft and Structure (What makes it work)

The film’s structure is built like a moral funnel. It starts with mass violence, then narrows into a small group, then narrows further into one man’s survival debt. That compression is the point. The story asks the viewer to move from history-as-spectacle to history-as-personal-cost.

The camera style and pacing reinforce the idea that war is confusion rather than choreography. The beach sequence sets the physical language: fast movement, disrupted clarity, bodies as obstacles, and sound as a threat. Later scenes slow down just enough to let moral choices land. The church scene and the prisoner scene are not breaks from the film. They are the film’s argument in human form.

The screenplay also uses contrast as a weapon. It cuts from administrative decisions to human consequences. It moves from open battlefields to cramped stairwells. It shifts from distant rifle fire to the intimacy of a knife. These choices force the viewer to feel the scale of war and the closeness of death without letting either become familiar.

What Most Summaries Miss

Many summaries treat the mission as the main point: find Ryan, bring him home, a battle happens, and a moral line delivered. The deeper structure is that the mission is a test case for how institutions justify sacrifice.

The Army’s order is not presented as purely noble or purely cynical. It is presented as a symbolic act that might be humane, and might also be propaganda, and might also be both at once. The film’s power comes from refusing to resolve that ambiguity. It makes the squad live inside the contradiction rather than explaining it away.

Another overlooked element is that Miller’s leadership is not glorified. The film shows that he makes decisions that get men killed. It shows him hiding weakness. It shows him needing meaning as much as anyone else. When he says “earn it,” it is not a clean moral command. It is a desperate attempt to keep death from being meaningless.

Relevance Today

The politics of “one life” versus “the many”: Modern crises still trigger the same argument, whether it is about hostage rescues, resource allocation, or emergency triage. The film dramatizes how quickly people stop being individuals and become “numbers,” then shows the emotional cost of resisting that logic.

Information overload and moral distance: News feeds make conflict feel constant but distant, which can numb empathy. The film forces proximity. It reminds viewers that behind any headline are bodies, choices, and families receiving telegrams that change everything.

Workplace leadership under burnout: Miller’s shaking hand is a small image with modern resonance. Many professionals lead while depleted, hiding stress because admitting it feels like weakness. The film shows the hidden cost of being the one who must keep others moving.

Rules under pressure in polarized culture: The prisoner debate mirrors modern fights over due process, punishment, and “exceptions” during fear. The film shows how quickly people decide rules are optional when they feel hurt and how hard it is to defend ethics when emotions demand revenge.

The psychology of veterans and moral injury: Beyond trauma, the film shows moral injury: the damage done when you violate your own values or fail to act. That concept connects to soldiers, first responders, and anyone whose job forces choices that haunt them.

The social media performance of sacrifice: Modern culture often celebrates sacrifice as content: clips, slogans, and hero narratives. The film warns that sacrifice is not a brand. It is a loss that leaves survivors carrying questions that no applause can answer.

Technology’s role in how violence is seen: The film’s realism changed expectations for how war looks on screen. Today, drones, phone footage, and real-time conflict clips shape public perception. The same question remains: does seeing more make people understand more, or does it just make suffering easier to scroll past?

Ending Explained

The ending returns to the cemetery to reveal what the mission really produced. It did not produce peace. It produced a man who lived, built a family, and still carries the weight of the dead as if it is his job to justify them.

The ending means the film’s true conflict is not Germany versus the Allies, but meaning versus emptiness. Miller cannot stop the war. He can only decide what kind of man he is inside it. By telling Ryan to “earn it,” he tries to leave Ryan with a path: live in a way that honors the men who died, so their deaths are not just random cruelty.

The ending also refuses closure. Ryan’s question to his wife is not answered by the film, because no answer can balance the scale. The cemetery image suggests that memory is the final battleground. The war ends, but the moral accounting does not.

Why It Endures

Saving Private Ryan endures because it refuses to treat war as entertainment or morality as a speech. It shows the machinery of violence and then asks what happens inside people forced to operate that machinery.

It is for viewers who want a war film that confronts cost without flinching and for anyone interested in leadership, ethics, and what survival does to identity. It may not work for those who want comfort, clean heroism, or distance from brutality, because the film is built to remove those buffers.

In the end, the story leaves you with a question that is both personal and political: if someone paid for your life with theirs, what would you do with the time you got?