The Great Depression? The Main Drivers, Ranked

The Great Depression did not begin with a single bad day on Wall Street, even if the crash of October 1929 is still the famous image. It was the product of a chain of failures in markets, banks, policy, and international cooperation that turned a sharp slowdown into a decade-long catastrophe.

It matters now because those same fault lines keep reappearing in new forms: fragile banks, heavy debt, sudden panics in markets, and governments moving too slowly or in the wrong direction. Understanding what truly caused the Great Depression is a way of stress-testing today’s economic system.

This piece ranks the main causes, from most decisive to more indirect, and explains how each one made the collapse deeper and longer than it had to be. It then looks at who was hit, what changed in politics and society, and what lessons still shape economic policy.

The story turns on whether governments and central banks learn from past crashes or repeat them in slower motion.

Key Points

The Great Depression was not caused by the stock market crash alone; it was a credit and banking collapse that policymakers failed to stop in time.

The single biggest driver was a severe contraction in money and credit, as banks failed and central banks kept policy tight instead of flooding the system with support.

The global gold standard turned national crises into a worldwide downturn by forcing countries to defend fixed exchange rates even at the cost of mass unemployment.

High debt, war reparations, and fragile international lending set up a system where any shock could trigger a global chain reaction.

Income inequality and weak consumer demand meant the boom of the 1920s rested on a narrow base, leaving households too stretched to absorb shocks.

Policy errors such as higher tariffs and premature attempts to balance budgets deepened and prolonged the slump instead of easing it.

The Great Depression reshaped politics, social safety nets, and the role of the state in the economy for generations.

Background

The Great Depression began in the United States after the stock market crash of October 1929 and then spread across the world. By the early 1930s, industrial output had fallen sharply, world trade had collapsed, and unemployment had soared in many countries. In the United States, roughly one in four workers was jobless at the peak.

But the crash itself was more of a trigger than a root cause. It exposed deeper problems built up through the 1920s: speculative bubbles, fragile banks, unbalanced global finance, and a rigid commitment to the gold standard.

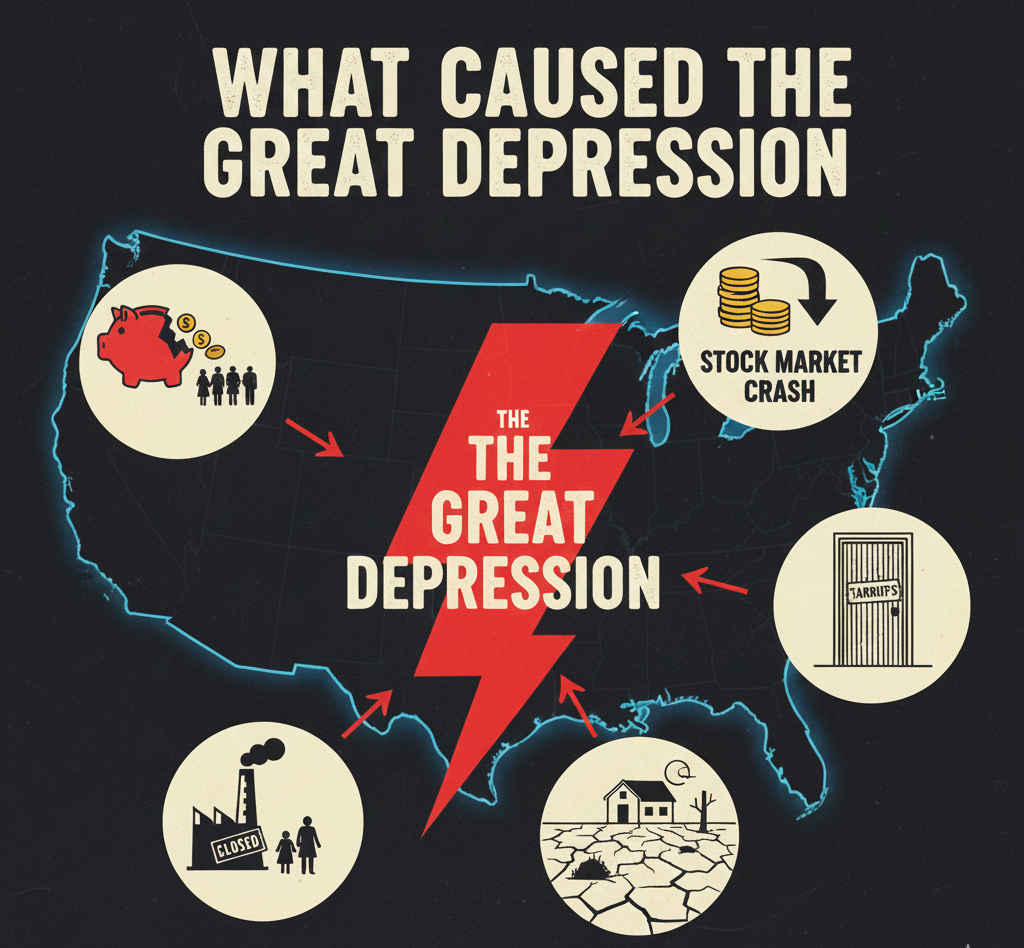

Economists and historians now tend to agree on several main causes. While they debate the exact ranking, the following order captures the forces that did the most damage:

Monetary and banking collapse: A wave of bank failures, falling money supply, and tight central bank policies that turned a sharp slowdown into a deflationary spiral.

The gold standard: A rigid global currency system that forced countries to raise interest rates and cut spending even as their economies fell.

Debt overhang and global imbalances: Heavy war debts, reparations, and risky cross-border lending that left the world economy vulnerable.

Structural weaknesses and inequality: A consumer economy built on fragile demand and uneven income distribution.

Policy mistakes after the crash: Trade barriers, budget tightening, and slow relief efforts that deepened and prolonged the downturn.

Each of these causes interacted with the others. None alone would likely have produced a decade of misery. Together, they created a crisis that reshaped the modern world.

Analysis

Political and Geopolitical Dimensions

Politically, the roots of the Great Depression lay partly in the unresolved legacy of the First World War. The peace settlement left some European countries with heavy reparation payments and others with large war debts. The United States became a key creditor, lending heavily to Europe in the 1920s.

This created a fragile triangle: American loans flowed to Europe; reparations flowed from defeated countries to their former enemies; war debt payments flowed back to the United States. When the American financial system cracked, this triangle fell apart.

The gold standard tied major economies together. Governments saw sticking to gold as a symbol of strength and credibility. In practice, it limited their ability to respond. When money flowed out of a country, the rules pushed authorities to raise interest rates and cut spending to defend the currency, even if unemployment was already high.

These choices were political as much as economic. Leaders feared that abandoning gold would signal weakness or invite chaos. The result was a worldwide chain reaction: one country’s cutbacks forced pain on its trading partners, who then made similar choices.

The crisis also altered the political landscape. In some places it fed radical movements and authoritarian regimes. In others, it opened the door to new social contracts and welfare systems. The Depression became a test of which political systems could adapt and which broke under pressure.

Economic and Market Impact

The economic story starts with the boom of the late 1920s. Stock prices rose far faster than company profits. Easy credit encouraged speculation. When confidence finally cracked, asset prices dropped sharply and margin borrowers were forced to sell into a falling market.

The crash wiped out wealth, but the deeper damage came from the response of banks and central banks. Many banks were poorly capitalized and heavily exposed to falling loans and defaults. As nervous depositors rushed to withdraw savings, waves of banks failed.

Instead of acting as a strong backstop, central banks allowed the money supply to shrink. Credit became harder to get. Prices and wages fell. Businesses delayed investment. Households postponed spending. Deflation meant that the real value of debts rose, making it even harder for borrowers to stay afloat.

The gold standard amplified this contraction. To stay on gold, countries did not cut interest rates aggressively or expand credit. They often did the opposite. That is why the countries that abandoned gold earlier tended to recover sooner.

Trade was hit next. As domestic markets shrank, governments tried to protect local jobs with tariffs and import restrictions. These measures choked off global demand further. Exporters lost markets just when they needed them most. World trade collapsed far more than world output.

In short, the Great Depression was above all a monetary and banking disaster. The stock market crash lit the fuse, but the explosion came from a system that allowed the financial fire to spread unchecked.

Social and Cultural Fallout

The human cost of the Great Depression was severe. Mass unemployment meant not just lost income but lost identity and status. Families moved in with relatives, skipped meals, or relied on charity. Young people delayed marriage and children. In some regions, entire communities were hollowed out.

Inequality made the pain uneven. When the boom had been driven by high profits and rising wealth at the top, the bust left many ordinary households with little cushion. Those who had savings saw them eroded by bank failures or deflation. Those living paycheque to paycheque fell quickly into hardship.

The crisis also shifted attitudes. Faith in unregulated markets weakened. Demand grew for safety nets, labor protections, and greater state involvement. Cultural narratives reflected this change, with more stories about ordinary people fighting hardship and less blind celebration of speculators and tycoons.

These social shifts did not all move in the same direction. In some settings, fear and anger were channelled towards scapegoats and minorities. In others, they were directed into new forms of solidarity and reform. The Depression made social cohesion a central question of modern politics.

Technological and Security Implications

Technologically, the Great Depression did not come from a single invention or breakthrough. Yet technology shaped the context. Increased industrial productivity in the 1920s made it possible to produce more goods with fewer workers. Without matching growth in wages and demand, this contributed to overcapacity and downward pressure on prices.

Transport and communications technology already linked markets tightly. That made it easier for financial panic and falling demand to spread across borders. A local downturn no longer stayed local for long.

In terms of security, economic collapse became a strategic risk. Struggling economies cut military spending in some cases but also became more vulnerable to internal instability and external pressure. The link between economic failure and political extremism became painfully clear in the years that followed.

The lesson for later generations was simple but hard to apply: in a tightly connected world, financial regulation, crisis management, and international coordination are themselves forms of security policy.

What Most Coverage Misses

Many simplified accounts still frame the Great Depression as “the stock market crashed and everything fell apart.” That story understates the damage done by policy choices after the crash and the deep vulnerabilities built up beforehand.

One overlooked factor is how much the commitment to the gold standard shaped everything else. Leaders who might have been willing to support banks or boost spending felt trapped by the need to defend their currencies. Staying on gold was treated as a moral and strategic duty, even as it forced them to accept mass unemployment. The gold standard turned a downturn into a global straightjacket.

Another underappreciated point is how central banks could have changed the outcome. If they had acted more aggressively to support banks, provide liquidity, and prevent deflation, the 1930s might still have been painful but much shorter. The Great Depression was not just a market failure. It was also a failure of imagination and speed among those with the tools to limit the damage.

Why This Matters

The Great Depression still shapes how central banks and governments respond to crises. Modern tools such as deposit insurance, lender-of-last-resort facilities, and large-scale asset purchases exist partly to avoid repeating the errors of the 1930s.

In the short term, the main lesson is about urgency. When banks look fragile or credit conditions tighten rapidly, waiting and hoping can be the most dangerous option. The longer authorities delay, the harder it becomes to stop fear from feeding on itself.

In the long term, the story raises deeper questions about how much inequality an economy can carry before it becomes unstable, how to manage global currency and trade systems, and how to balance market freedom with safety nets.

Concrete events that often revive debate about the Great Depression include major bank failures, sharp downturns in trade, or high-profile shifts in monetary policy. Each time these arise, comparisons with the 1930s return, and the same questions resurface: will policymakers move fast enough, and will they avoid turning a shock into a slump?

Real-World Impact

A small manufacturer in the Midwest sees orders dry up as nervous retailers cut back. The owner has to choose between keeping staff on and risking bankruptcy or laying workers off to survive. In the 1930s, many chose the latter because credit lines had vanished and no backstop was in sight.

A farm worker in a drought-hit region faces falling crop prices and rising debts. Without support programs or insurance, a bad season means losing the land entirely. In the Great Depression, this pattern pushed thousands of families into poverty and migration.

A bank clerk in a regional town watches customers queue to withdraw savings. With no deposit insurance, every rumor can spark a run. The clerk knows that if the bank fails, staff may not be paid and depositors will lose years of savings overnight.

A young graduate in a big city struggles to find work as companies freeze hiring. Without strong social safety nets, moving back in with family or joining relief programs becomes the only option. The experience shapes attitudes towards risk, saving, and the role of government for the rest of that person’s life.

Legacy

The Great Depression was not a mystery bolt from the blue. It was the result of a highly ranked chain of causes: a severe monetary and banking contraction at the top, amplified by the gold standard, debt and global imbalances, structural inequality, and a series of damaging policy choices after the crash.

The core tension is still with us. Financial systems need enough freedom to allocate capital and encourage risk-taking, but enough safeguards to prevent panics from spiraling into collapse. Governments must balance credibility with flexibility, and national interests with the realities of an interconnected world.

The clearest signs of which way the story is going in any new crisis are always the same: how central banks treat failing institutions, whether governments protect the most vulnerable, and how quickly leaders are willing to abandon rigid rules that no longer fit the moment. The shadow of the Great Depression falls on those choices every time they are made.